Germany’s motorways are often thought to be very well-run and a model for others to follow. From surface condition to roadside amenities, Germany knows how to get people from A to B as fast and pleasantly as possible. However, as well-run as they might be, few people realise that until this year, the nation’s motorways had no central organisational structure.

Being a federal republic, Germany has 16 partly-sovereign states, or Lands. For more than 60 years, each of the Lands had been operating and maintaining their section of national highways. But in 2018, changes started happening. Over the following three years, these responsibilities were gradually transferred to a new single motorway agency, Die Autobahn des Bundes, or simply Autobahn.

On 1 January this year, Autobahn was officially declared up and running for business. The agency is now responsible for 13,200km of motorways throughout the country, including 28,000 bridges, 550 tunnels and around 6,300 ongoing highway projects.

The change to one overall agency was needed, explains Gerd Riegelhuth, who heads up traffic management, transport and operations. There now needs to be a much more coordinated development of ITS, especially traffic telematic systems and cooperative systems such as for autonomous driving. There were 11,000 people employed within the 16 independent traffic management organisations.

Cultural change

“It was not simply an organisational change but also a cultural one,” says Riegelhuth who was on hand to talk at the recent ITS World Congress in Hamburg, Germany. It was the first time, given past Covid restrictions, that the team at Autobahn could get out and introduce themselves in person as well as the new agency and discuss plans for the future with the transportation sector. “This meant that there were 16 different philosophies of how to operate motorways, build roads and so on. Each state had a different level of knowledge of ITS and also they employed often different management systems.”

There were different standards, 16 different computer architectures and little interoperability of the control centres, he says. “Regarding ITS, this is a big challenge for us. We aim to connect the traffic centres to manage European-level traffic corridors throughout Germany. In the past the focus of each traffic centre was to manage only up to the federal state’s borders. Our goal is to have a national view of traffic management and the entire network.”

The state of Hessen, which includes Frankfurt, contained the largest and most advanced traffic centre in the country - now called Traffic Centre Germany. There are seven regional traffic control centres, each overseeing a pan-European corridor and located in Germany’s largest metropolitan areas, including Hamburg, Berlin, Leipzig, Munich and Leverkusen.

Euro 2024 goal

The goal, says Riegelhuth, is to have these centres completely interoperable by kick-off of the European football championship in summer 2024. Germany is hosting, for the third time, the championship and the games will be played in 10 cities, meaning the motorways will be very busy. By the end of 2023, there will be common operating standards and systems.

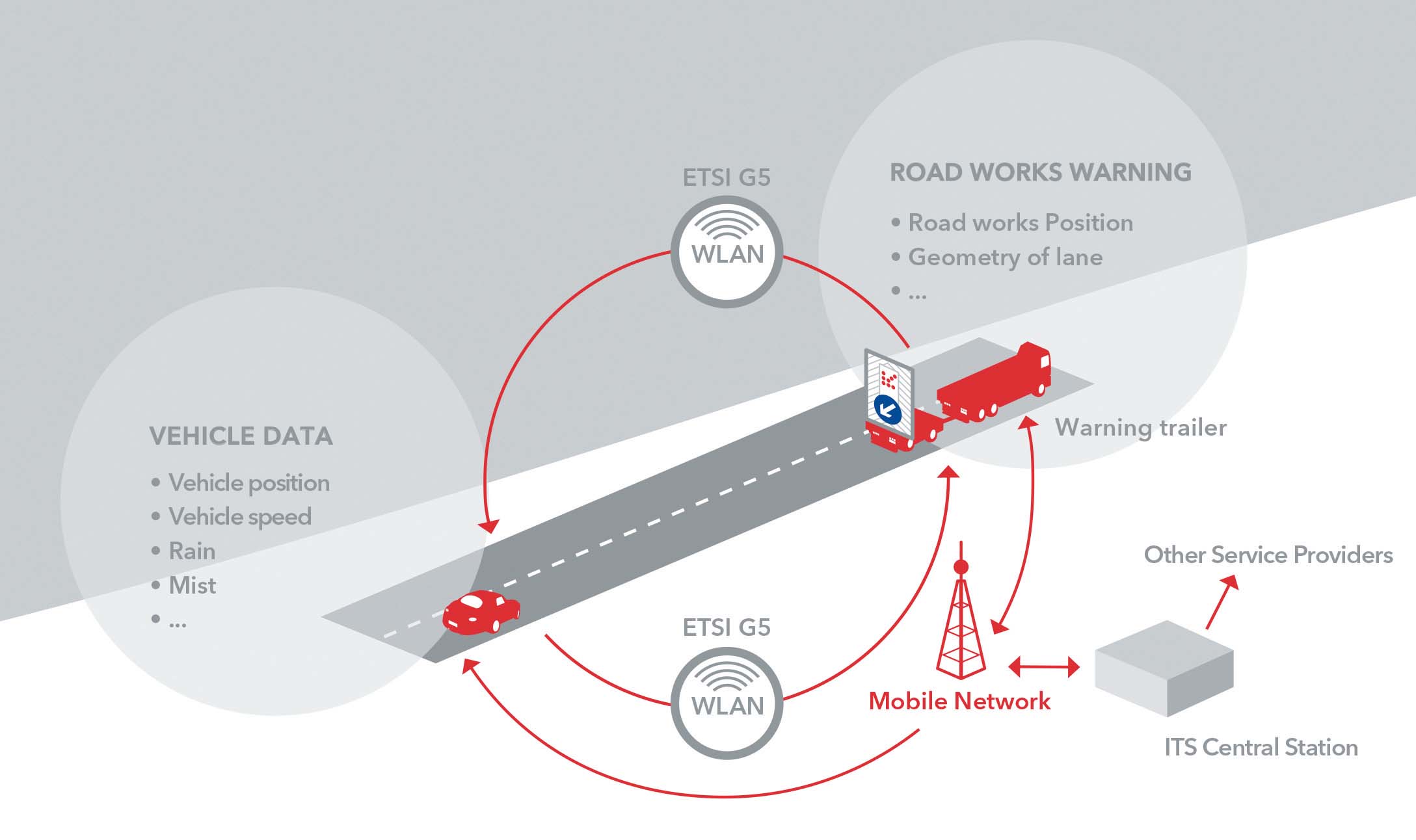

A major focus for Autobahn is the setting up of cooperative car-to-car applications. “In April this year we introduced the first European service as a cooperative system regarding roadworks warning.”

This was done in cooperation with Volkswagen using their recently-launched electric vehicles - the ID 3 introduced in 2019 and the more powerful and more rapid-charging ID 4, launched earlier this year. The vehicle on-board units receive roadworks warning messages sent from Autobahn trailers parked near the work sites.

Because Autobahn is a new organisation, it has less organisational baggage as it moves into a more technologically sophisticated future, meaning it can question past processes and systems. The cooperation agreement with Volkswagen raises the issue of a holistic approach to motorway management for agencies such as Autobahn, Riegelhuth says. To what extent does an agency like Autobahn have the responsibility of the agency to develop safety systems? To what degree is this done in isolation from vehicle manufacturers?

“For example, we are beginning discussions with vehicle manufacturers about what they believe the role of the motorway operator should be in the future. But also, what is the role and what are the responsibilities of the automakers?”

Autonomous vehicle trial

Safety remains paramount when it comes to motorway operations. “We have tested an autonomous safety truck with a warning arrow alerting drivers to change lanes because of roadworks ahead. It ran along the hard shoulder, so for us the best situation is if no-one is driving this safety vehicle, which is a hazardous job,” he says. “It was a successful demonstration of the possibilities of autonomous safety vehicles and we are now in discussions with the automotive industry to develop this application. The next step is to have the safety vehicle travelling along a live driving lane.”

Importantly, the autonomous safety vehicle project was done in conjunction with the Dutch transport agency Rijkswaterstaat. It points to the need for cooperation among European partners to develop common standards and protocols for such warning systems that use communications between vehicles and infrastructure. This leads to harmonisation of specifications for future Vehicle to Everything (V2X) systems.

“Let’s face it, you drive your car from Scandinavia to Austria and there should not be different V2X applications in each country. Your technology should work for you, everywhere, all the time.”

About the Author:

David Arminas is deputy editor of ITS International’s sister magazine World Highways