Cities have a moral responsibility to encourage the smart use of transportation and Andrew Bardin Williams hears a few suggestions.

Given the choice of getting a root canal, doing household chores, filing taxes, eating anchovies or commuting to work, nearly two-thirds of Americans said that they wouldn’t mind commuting into work—at least according to a poll conducted by

People are seemingly happy with their commutes - whether they walk, cycle, drive, carpool or take public transit - but you won’t see transportation officials jumping for joy any time soon. Congestion, emissions, public safety and public health continue to be major issues in our largest cities. Americans remain addicted to single-occupancy commuting and local transportation departments still need to encourage smarter transportation habits.

“Driving is habitual,” explains Matt Darst, vice president, parking and mobility solutions for Conduent—a new transportation consulting company recently spun off from Xerox. “People aren’t aware of the options they have.”

Moral imperative

It can be argued that local transportation agencies have a moral imperative to educate commuters on better options and provide them with the tools that make it easier to make smarter commuting decisions. Dangerous emissions exacerbated by congestion, the inability for emergency vehicles to travel through traffic and the danger posed to pedestrians from vehicle traffic are public safety issues that fall under the responsibility of government officials. Traffic also affects the flow of people and goods in a bustling economy as well as policing strategies.

Darst suggests that transportation agencies can change commuters’ behaviour by subsidising public transportation as well as shared-use commutes. Subsidising public transit systems is nothing new. Most transit agencies are subsidised by taxpayers’ money—though not as much as highways and surface roads.

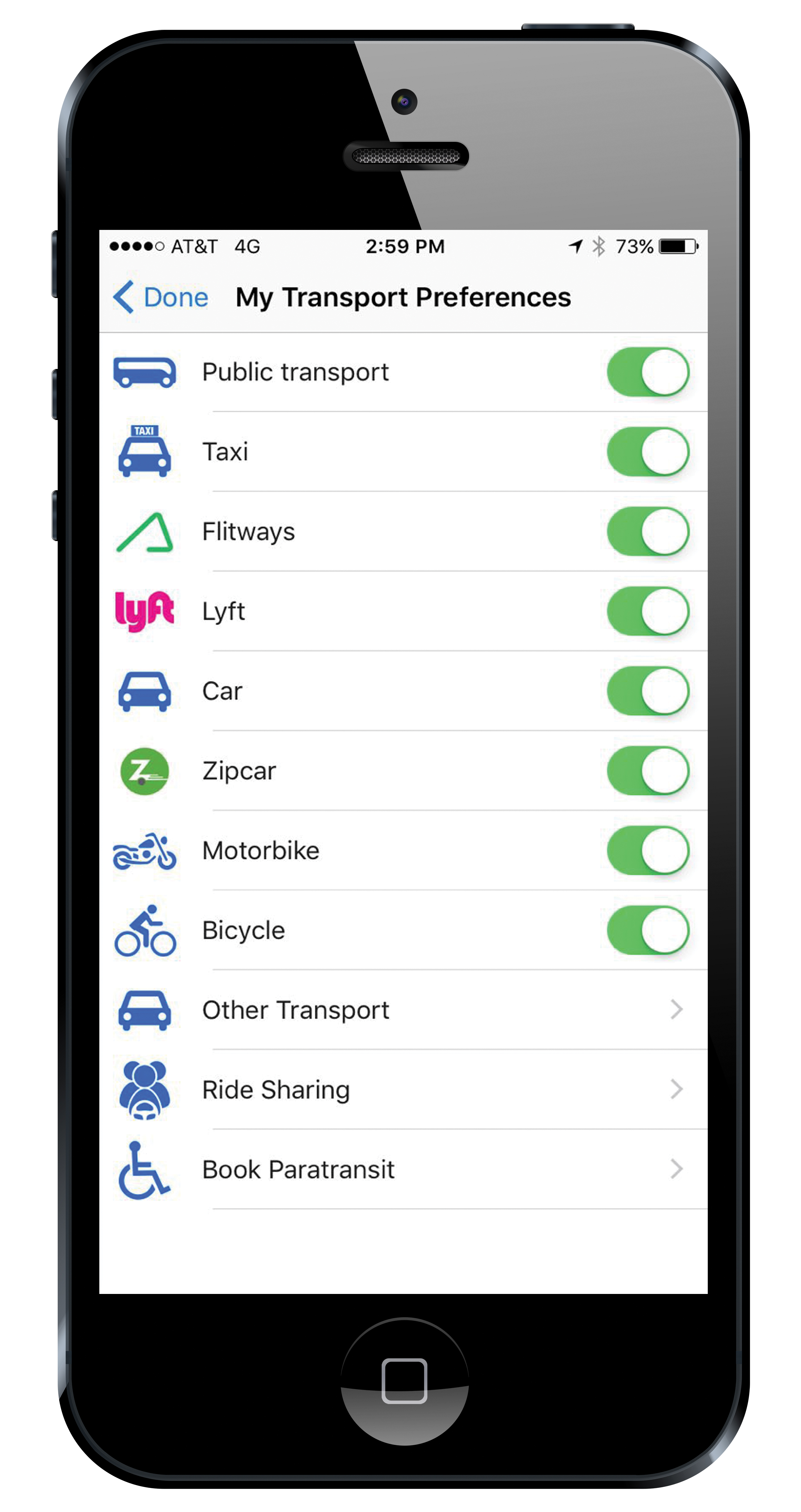

And now, a few municipalities are leveraging private shared-use providers to help bridge gaps in transportation services.

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Agency (MBTA) has a partnership with Lyft and Uber to complement its RIDE paratransit service that provides special needs riders with on-demand transportation across the region. Riders pay the first $2, and MBTA will pick up the remaining cost of the trip up to $13.

A similar programme in the St. Petersburg, Florida, area provides subsidised Uber, Lyft or taxi rides to and from selected bus stops, helping to bridge the first/last mile gap.

Centennial, a suburb of Denver, has also teamed up with Lyft to provide free rides to its Dry Creek Light Rail station.

The most aggressive subsidy is offered by Altamonte Springs in Florida which subsidises 20% of all Uber rides that begin and end inside city limits and 25% of rides that start or end at the Orlando light rail system.

Everybody’s problem

“We all have a role to play to solve these stubborn municipal problems. It’s an opportunity to reduce costs without cutting service completely,” Darst says.

While subsidies encourage preferable commuting behaviour, transportation agencies can also discourage poor driving habits by implementing demand pricing policies—kind of a stick versus the carrot approach.

According to Darst, US cities have danced around the issue for decades but have yet to implement much meaningful progress.

Demand pricing parking has taken root in some cities but charging single-occupancy vehicles a fee to drive on public roads has yet to catch on—mainly because, according to Darst—toll roads, the most obvious way to implement demand pricing, are controlled on the state level rather than by municipalities.

“The ability to charge more for single-occupancy vehicles can change behaviour significantly,” Darst said.

Carpooling and ridesharing

Carpooling is a great way to reduce traffic volume without asking commuters to radically change their commute behaviour. However, making connections between riders and drivers can be tricky.

James Glasnapp, senior UX researcher at Xerox company PARC, has studied people’s mobility needs for years. He recently focused his attention on carpooling and private ridesharing, even becoming a carpool driver through three different companies in the Bay Area to gain a deeper understanding into the driver’s point of view.

Based on his research, he’s come up with nine conditions he thinks a carpooling offering needs to be successful. First and foremost, he says the offering must be mutually beneficial for both the rider and the driver, so they feel like the system was built specifically for them. Additionally, he says the offering must allow drivers to choose the distance they’re willing to deviate from their usual journey to pick up other riders.

Encouraging sharing

Here are his nine tips for local transportation agencies and app developers to encourage carpooling and ridesharing:Offerings must be equally rider- and driver-centric, as stated earlier. Some offerings cater more to one or the other, but both riders and drivers must experience a version of the system that makes them feel the system was built for them.

The price must incentivise drivers while not deterring riders. Glasnapp believes the right amount seems to be the current governmental reimbursable rate for mileage which, at $.54 per mile in 2016, is less than competing alternatives like Uberpool or Lyft Line. In addition, the length of the ride must also match driver expectations for compensation. In Glasnapp’s case, his commute is 64km (40 miles), and if he had the opportunity to give a ride to someone that would take him off route for 17 minutes (roughly a third of his commute) yet only pays him $6.99, it would not be worth the time and effort.

Pick-up and drop-off must be in ‘sweet zones’. Sweet zones indicate the distance drivers are prepared to deviate from their usual journey in order to pick-up or drop-off riders and is as, or more, important than the length of the rideshare itself. As the sweet zone varies by driver, a recommended app feature would allow drivers to generate their own personal zone, indicating how far they are willing to deviate. This could be set by distance or by time (say 10 miles off route or an additional 10 minutes).

Systems must be able to learn and improve. Riders and drivers should be able to give feedback on quality of routes and riders, for instance. A mechanism to gather that feedback should be built into the app.

Drivers should have moderate insight and control into how and when they receive ride requests. One carpool system Glasnapp tried did not give drivers any input into managing their drive, and it was chaotic while another gave too much, and was burdensome. A third was clear about when it would accept ride requests for either driver or rider, which was useful but it became inflexible because after the cut off points, users couldn’t make changes without being penalised. Prior to the cut-off points, users did not know if rides had been accepted.

Safety and comfort must be considered. With carpooling, drivers and riders are concerned about safety, privacy and comfort—more than with other types of ride-sharing, which are often shorter rides. Longer routes give carpooling an intimacy.

People care who they are going to spend time with in close quarters for longer periods of time. One of the systems Glasnapp tried linked to Facebook and LinkedIn to profile the users, so people on the ‘other end of the app’ are known entities before any rides take place. If a user does not attach a profile, drivers or riders can choose to reject the request. All systems allowed drivers and riders to rate each other and block future contact if things didn’t go well. Having picked up a rider who was rushing through breakfast in his car, and because of other personal hygiene habits, Glasnapp blocked future requests from that person.

A culture of carpooling needs to be developed. Although the driver often dictates the culture, it would be helpful for the website or app to have a suggested etiquette for both riders and drivers. As carpooling grows, this would help users know how to behave and understand the culture.

Choice is essential. As the number of riders and drivers expands in a system, riders and drivers will be able to drill down to more specific requests—things like a quieter car, a limited number of pickups, the ability to participate in conference calls during the ride and smoking and eating options.

Drivers should have the option of taking multiple riders. Only one service used by Glasnapp used gave the opportunity to pick up two riders at once - and that app does not allow the driver the option of limiting pickups. Riders may be willing to pay more for a solo ride, but, theoretically, allowing for multiple riders would bring costs down for the riders, while the driver could earn additional income, particularly if the riders live or work in close proximity to each other.

Ridesharing and carpooling have a tremendous potential for reducing congestion and offering services to individual riders who may otherwise face difficulties travelling. In facilitating these services and rewarding drivers (financially or otherwise) authorities are improving conditions for drivers and the public alike – be they city residents, commuters or paratransit users.