Public acceptance is crucial for the acceptance of managed and express lanes as Jon Masters discovers. Lists of proposed highway expansion projects introducing variably priced toll lanes continue to lengthen. Managed lanes, or express lanes to some, are gaining support as a politically favourable way of adding capacity and reducing acute congestion on principal highways. In Florida, for example, the managed lanes on the 95 Express are claimed to have significantly increased average peak-time speeds on tolle

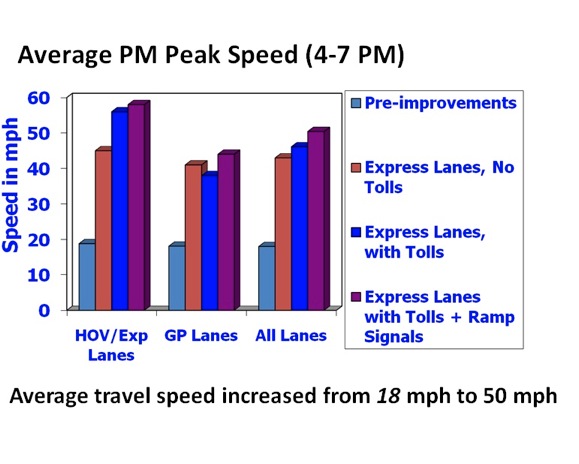

Average travel speed increased from 29km/h to 80km/h (18mph to 50mph)

Public acceptance is crucial for the acceptance of managed and express lanes as Jon Masters discovers.

Lists of proposed highway expansion projects introducing variably priced toll lanes continue to lengthen. Managed lanes, or express lanes to some, are gaining support as a politically favourable way of adding capacity and reducing acute congestion on principal highways. In Florida, for example, the managed lanes on the 95 Express are claimed to have significantly increased average peak-time speeds on tolled and non-tolled traffic lanes.

Managed lanes still represent a tiny minority of US highways, however, and not all projects are benefitting from the same political support and the importance of concerted campaigns to communicate the benefits is becoming ever clearer.

Florida and California are making some of the biggest moves to implement managed lanes. The Bay Area Infrastructure Financing Authority is reported to have begun procuring toll equipment suppliers for 145km (90 miles) of managed lanes on the I-80, I-680 and I-880. In Miami, phase two of Florida DOT’s 95 Express Lanes Programme is due to open this year. Reversible variably priced lanes are being added to the I-595 near Fort Lauderdale and Florida has approved similar projects on I-75 in Broward County and the Palmetto Expressway in Miami-Dade County.

Elsewhere, a contractor has been selected for the $834 million reconstruction of I-75 and I-575 in Atlanta with additional managed lanes, while in Los Angeles, the $1.3 billion widening of SR 91 is expected to start in 2014, extending the existing express lanes from the Orange County line into Riverside County.

The growing list of approved schemes only represents the tip of an iceberg given the volume of projects currently at early stages of development. Garnering public and political support will be critical, and not easy, for the many state and city departments keen for an affordable solution to acute traffic congestion.

A big hurdle to overcome is the general lack of awareness among the public. “Many states have been on a steep and severe learning curve. Minneapolis tried to implement tolled lanes three times before getting a satisfactory result,” says the chair of the Transportation Research Board’s managed lanes committee Chuck Fuhs.

“States generally need to demonstrate enough positive experience of tolled lanes to generate a groundswell of support, plus it needs a generation of the public to have been around and adjusted to it. With managed lanes it is not just a tolling issue. The principle is based on managing something to keep it operating below its capacity, so it may appear empty. Convincing the public of the logic in this presents a big challenge. A much higher plateau of marketing is needed.”

According to Fuhs, there is a general public view that the federal gas tax covers all that’s needed for highway construction; paying for tolls, variably priced or not, means paying for the same thing twice.

However, in 2013 the National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board (TPB) in Washington DC concluded that it didn’t know what the public thinks of traffic congestion and of road pricing and tolling as ways of reducing it.

So it embarked on a major fact-finding mission via public surveys and a series of organised forums in Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

According to the TPB’s full report on public views of congestion pricing, participants in the public forums were asked to put forward their views, via keypad voting and paper surveys, on the region’s traffic problems, They were given three possible scenarios: variably priced lanes on all major highways; variable pricing on all roads and streets using vehicle-based GPS systems; and zones where drivers are charged a fee to enter designated areas.

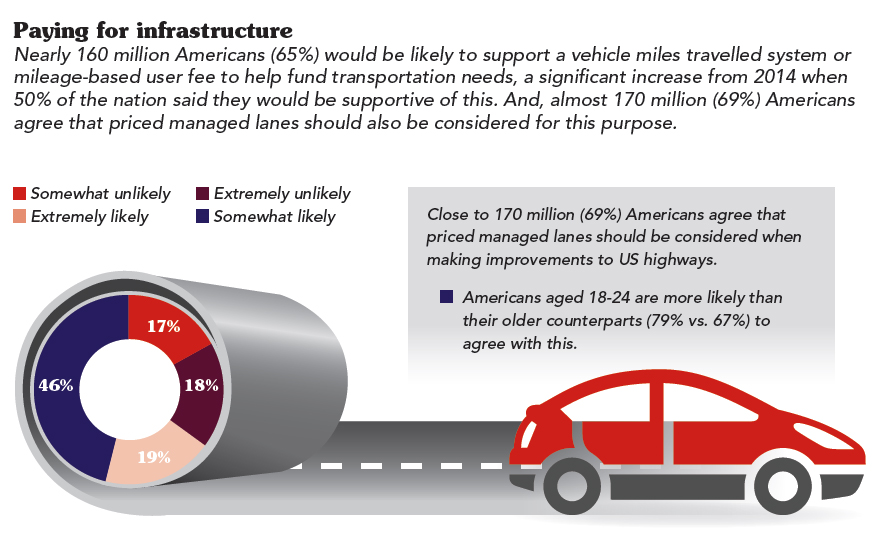

The results, in part, back up Fuhs’ impression of public knowledge and opinion. ‘Participants were generally unaware of the details of how transportation is currently funded, including the fact that the federal gas tax has not been raised in nearly two decades and is not indexed to inflation,’ the TPB’s report says.

Of the three scenarios, variably priced lanes on all major highways gained the most support with 60% of forum participants saying they would back it, partly because it presents drivers with the option to opt in or out.

This is a key finding of TPB’s initiative. Strong support can be gained if increased choice and fairness are demonstrated. The ‘Lexus Lane’ argument against managed lanes (scenario one) is not commonly held, according to TPB. A system that maintains the option to opt out is more important than the notion that variably priced lanes are there just for those who can afford them.

Other results showed strong opinion against GPS-based road charging (90% against) and were inconclusive with regard to cordon-based pricing (50%). Congestion pricing proposals must state a compelling value proposition, such as increased choice and individual control, the TPB recommends. Pilot schemes will reduce scepticism, as will education campaigns and incremental implementation, the report adds.

These findings are already being borne out in some areas with an established history of implementing tolling projects.

“In Miami, the 95 Express says quite a lot about why some schemes are successful and gain the necessary political support while others do not,” says Florida DOT director of transportation operations Debora Rivera.

“We had a number of key ingredients in place. We had a severely congested highway with HOV lanes failing because they had reached capacity. South Florida had a long successful history of toll roads, with an outstanding job done by toll operators, plus we had a very good commuter assistance programme of car sharing and van pooling in place, which was another key advantage. Other areas may be struggling to get public acceptance or political support because they have one or two of these key ingredients missing.”

The managed lanes of 95 Express were built in two stages between 2008 and 2010, along 13km (eight miles) of I-95 between Fort Lauderdale and downtown Miami, a stretch of highway serving Miami’s central business district, Fort Lauderdale airport and around 300,000 vehicles every day. Transit and HOV lanes had been built 30 years previously but, says Rivera, violation rates on these lanes and congestion in general had reached a point where people were desperate for a solution.

“There was no available footprint for widening and a double-decker solution had been considered, but the costs were huge. Fortunately, we had the Miami-Dade Expressway Authority which had already considered premium lanes within its fixed Toll facility and had done a lot of outreach with focus groups and elected officials,” Rivera says.

“When the831 Federal Highway Administration offered grant incentives for DOTs to come up with ways of solving congestion problems, we continued the Miami Dade Authority’s process. Some officials thought express lanes a bad idea, that people shouldn’t have to pay extra, but we explained it as a new choice, an alternative that will help people when they need it most.

“Trip reliability for those needing to catch a flight, for example, was terrible. We also pointed out that conditions will get better for those choosing not to pay the Toll as well, as Toll paying drivers leave the general purpose lanes. There were a number of key reasons and messages that made it work.”

Florida DOT pursued its public and media outreach programme through 2007 and had its design and build project underway by early 2008. The First tolls were being collected before the end of that year. “People saw an improvement quickly. We built and opened the northbound First rather than the whole lot in one go, which helped. It gave us a lot of encouragement and support for the second half,” Rivera says.

According to Florida DOT’s figures, by 2013 peak-time traffic speeds on the general purpose lanes of I-95 had increased from 29km/h to 64km/h (18mph to 40mph), and from 29km/h to 80km/h (18mph to 50mph)on the tolled Express Lanes. Furthermore, average daily transit patronage (on buses that automatically gain access to the Express Lanes) has risen from 1,900 to 5,400.

“Transit use has increased with some modal shift. Some park and ride facilities are now brimming. Folk that used to be in the car are switching to transit because it has become a viable alternative, which is the holy grail of transport programmes,” says Rivera.

Florida DOT has also had to pursue an ‘aggressive’ highway management strategy to make its express lanes scheme work, Rivera adds. Rapid-response recovery crews are coordinated from a strategic traffic management centre, with full routine maintenance carried out at the same time each week. All is designed to keep traffic disruption to a minimum, which has helped Florida DOT pursue further express lane projects on the adjoining Palmetto Expressway I-595 and I-75 routes.

“We are offering users a more reliable journey and increased speeds, which are important measures of success, plus it’s now financially self-sustaining,” Rivera adds.

Lists of proposed highway expansion projects introducing variably priced toll lanes continue to lengthen. Managed lanes, or express lanes to some, are gaining support as a politically favourable way of adding capacity and reducing acute congestion on principal highways. In Florida, for example, the managed lanes on the 95 Express are claimed to have significantly increased average peak-time speeds on tolled and non-tolled traffic lanes.

Managed lanes still represent a tiny minority of US highways, however, and not all projects are benefitting from the same political support and the importance of concerted campaigns to communicate the benefits is becoming ever clearer.

Florida and California are making some of the biggest moves to implement managed lanes. The Bay Area Infrastructure Financing Authority is reported to have begun procuring toll equipment suppliers for 145km (90 miles) of managed lanes on the I-80, I-680 and I-880. In Miami, phase two of Florida DOT’s 95 Express Lanes Programme is due to open this year. Reversible variably priced lanes are being added to the I-595 near Fort Lauderdale and Florida has approved similar projects on I-75 in Broward County and the Palmetto Expressway in Miami-Dade County.

Elsewhere, a contractor has been selected for the $834 million reconstruction of I-75 and I-575 in Atlanta with additional managed lanes, while in Los Angeles, the $1.3 billion widening of SR 91 is expected to start in 2014, extending the existing express lanes from the Orange County line into Riverside County.

The growing list of approved schemes only represents the tip of an iceberg given the volume of projects currently at early stages of development. Garnering public and political support will be critical, and not easy, for the many state and city departments keen for an affordable solution to acute traffic congestion.

A big hurdle to overcome is the general lack of awareness among the public. “Many states have been on a steep and severe learning curve. Minneapolis tried to implement tolled lanes three times before getting a satisfactory result,” says the chair of the Transportation Research Board’s managed lanes committee Chuck Fuhs.

“States generally need to demonstrate enough positive experience of tolled lanes to generate a groundswell of support, plus it needs a generation of the public to have been around and adjusted to it. With managed lanes it is not just a tolling issue. The principle is based on managing something to keep it operating below its capacity, so it may appear empty. Convincing the public of the logic in this presents a big challenge. A much higher plateau of marketing is needed.”

According to Fuhs, there is a general public view that the federal gas tax covers all that’s needed for highway construction; paying for tolls, variably priced or not, means paying for the same thing twice.

However, in 2013 the National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board (TPB) in Washington DC concluded that it didn’t know what the public thinks of traffic congestion and of road pricing and tolling as ways of reducing it.

So it embarked on a major fact-finding mission via public surveys and a series of organised forums in Maryland, Virginia and the District of Columbia.

According to the TPB’s full report on public views of congestion pricing, participants in the public forums were asked to put forward their views, via keypad voting and paper surveys, on the region’s traffic problems, They were given three possible scenarios: variably priced lanes on all major highways; variable pricing on all roads and streets using vehicle-based GPS systems; and zones where drivers are charged a fee to enter designated areas.

The results, in part, back up Fuhs’ impression of public knowledge and opinion. ‘Participants were generally unaware of the details of how transportation is currently funded, including the fact that the federal gas tax has not been raised in nearly two decades and is not indexed to inflation,’ the TPB’s report says.

Of the three scenarios, variably priced lanes on all major highways gained the most support with 60% of forum participants saying they would back it, partly because it presents drivers with the option to opt in or out.

This is a key finding of TPB’s initiative. Strong support can be gained if increased choice and fairness are demonstrated. The ‘Lexus Lane’ argument against managed lanes (scenario one) is not commonly held, according to TPB. A system that maintains the option to opt out is more important than the notion that variably priced lanes are there just for those who can afford them.

Other results showed strong opinion against GPS-based road charging (90% against) and were inconclusive with regard to cordon-based pricing (50%). Congestion pricing proposals must state a compelling value proposition, such as increased choice and individual control, the TPB recommends. Pilot schemes will reduce scepticism, as will education campaigns and incremental implementation, the report adds.

These findings are already being borne out in some areas with an established history of implementing tolling projects.

“In Miami, the 95 Express says quite a lot about why some schemes are successful and gain the necessary political support while others do not,” says Florida DOT director of transportation operations Debora Rivera.

“We had a number of key ingredients in place. We had a severely congested highway with HOV lanes failing because they had reached capacity. South Florida had a long successful history of toll roads, with an outstanding job done by toll operators, plus we had a very good commuter assistance programme of car sharing and van pooling in place, which was another key advantage. Other areas may be struggling to get public acceptance or political support because they have one or two of these key ingredients missing.”

The managed lanes of 95 Express were built in two stages between 2008 and 2010, along 13km (eight miles) of I-95 between Fort Lauderdale and downtown Miami, a stretch of highway serving Miami’s central business district, Fort Lauderdale airport and around 300,000 vehicles every day. Transit and HOV lanes had been built 30 years previously but, says Rivera, violation rates on these lanes and congestion in general had reached a point where people were desperate for a solution.

“There was no available footprint for widening and a double-decker solution had been considered, but the costs were huge. Fortunately, we had the Miami-Dade Expressway Authority which had already considered premium lanes within its fixed Toll facility and had done a lot of outreach with focus groups and elected officials,” Rivera says.

“When the

“Trip reliability for those needing to catch a flight, for example, was terrible. We also pointed out that conditions will get better for those choosing not to pay the Toll as well, as Toll paying drivers leave the general purpose lanes. There were a number of key reasons and messages that made it work.”

Florida DOT pursued its public and media outreach programme through 2007 and had its design and build project underway by early 2008. The First tolls were being collected before the end of that year. “People saw an improvement quickly. We built and opened the northbound First rather than the whole lot in one go, which helped. It gave us a lot of encouragement and support for the second half,” Rivera says.

According to Florida DOT’s figures, by 2013 peak-time traffic speeds on the general purpose lanes of I-95 had increased from 29km/h to 64km/h (18mph to 40mph), and from 29km/h to 80km/h (18mph to 50mph)on the tolled Express Lanes. Furthermore, average daily transit patronage (on buses that automatically gain access to the Express Lanes) has risen from 1,900 to 5,400.

“Transit use has increased with some modal shift. Some park and ride facilities are now brimming. Folk that used to be in the car are switching to transit because it has become a viable alternative, which is the holy grail of transport programmes,” says Rivera.

Florida DOT has also had to pursue an ‘aggressive’ highway management strategy to make its express lanes scheme work, Rivera adds. Rapid-response recovery crews are coordinated from a strategic traffic management centre, with full routine maintenance carried out at the same time each week. All is designed to keep traffic disruption to a minimum, which has helped Florida DOT pursue further express lane projects on the adjoining Palmetto Expressway I-595 and I-75 routes.

“We are offering users a more reliable journey and increased speeds, which are important measures of success, plus it’s now financially self-sustaining,” Rivera adds.