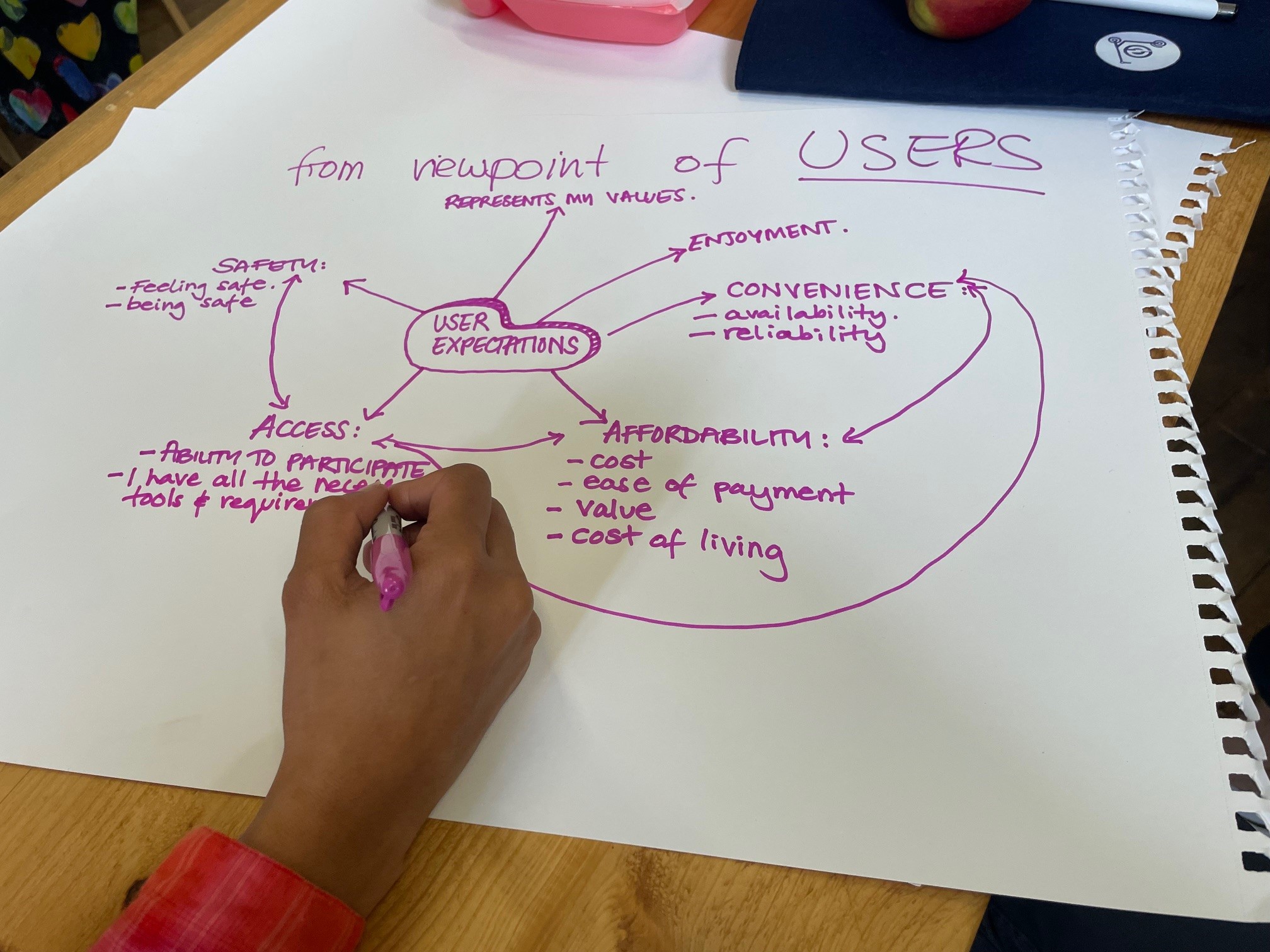

We are sitting in a room, writing down on big sheets of paper what we think users want from their journeys with shared cars, bikes or e-scooters - and also coming up with reasons why they might not want to use these services at all.

Around the room, other groups are doing the same, from the point of view of operators: the first day of Movmi's Shared Mobility Fall Masterclass: From Mindshift to Modeshift is well underway. Where are the gaps in shared mobility? Which are the underserved groups and what are their specific needs and challenges? More widely, how do you make mobility services inclusive and accessible to all?

I was invited to join the three-day course, which is supported by EIT Urban Mobility, and held at Loud Mobility's HQ in London, UK. Mobility professionals from countries including France, Sweden, Netherlands and Germany, as well as the UK, were in attendance.

My job is to write about mobility rather than shaping its services. In many situations it is my job to ask the 'stupid' questions; these often get the best answers. It saves other people being embarrassed, too: if I ask these questions, it means they don't have to.

The importance of asking 'stupid' questions

One of the chief pleasures of the Shared Mobility Fall Masterclass was spending time with people who know more than you, and who think differently about the same problems. Perhaps this goes for ongoing professional training more widely, too - either way, this is a large part of the reason why this course was among the most interesting educational events I've attended.

Back to the stakeholder mapping exercise. It is well known that women and men travel differently. The concept of 'trip-chaining' - making multiple short trips as part of a longer journey - is likely to be more apparent to women, who are often over-represented in caring responsibilities which necessitate taking children to doctor's appointments, or looking in on elderly relatives. Clearly there are differences in the way women and men move when it comes to safety considerations, too.

But it also emerged that some users might care that a brand or experience represents their own values, while others may also think it important that they get some enjoyment from the mode they use. 'Values' and 'enjoyment' have not necessarily been on my tick-box list when I'm writing about micromobility. They will be in my mind now.

Why aren't all users at the table?

In order for agencies and planners to make the most sensible decisions on mobility, all users need to be present at the table. So why are planning and business decisions often taken without reference to those who don't shout the loudest? Do we think enough about what the people who actually use shared mobility services really need, as opposed to what we think they need?

Many thanks to Natalia Le Gal, Georgia Yexley and Michael Glotz-Richter for leading the sessions on Day 1 - a more experienced crew would be hard to find.

Bringing shared mobility into neighbourhoods; behaviour change and user adoption; operational reality in London; mobility through partnerships; working with developers; and financing were among the other topics covered, with various workshops and external speakers,over the next two days of the course.

My favourite quote from the day was on e-scooters: "It's a relationship of love and hate with, quite often, nothing in between." Quite so. My impression is that scooter companies often don't help themselves in this regard, but that's another story for a different time.

Among the questions I took from the Shared Mobility Fall Masterclass were around the need to consider the difference in users' perceptions about what constitutes risk, or convenience, or a good experience, and so on. Also, we need data: but there are good reasons why shared mobility data points are not as reliable as we might hope - for instance, how do you report near-misses?

Also, be prepared to challenge yourself...

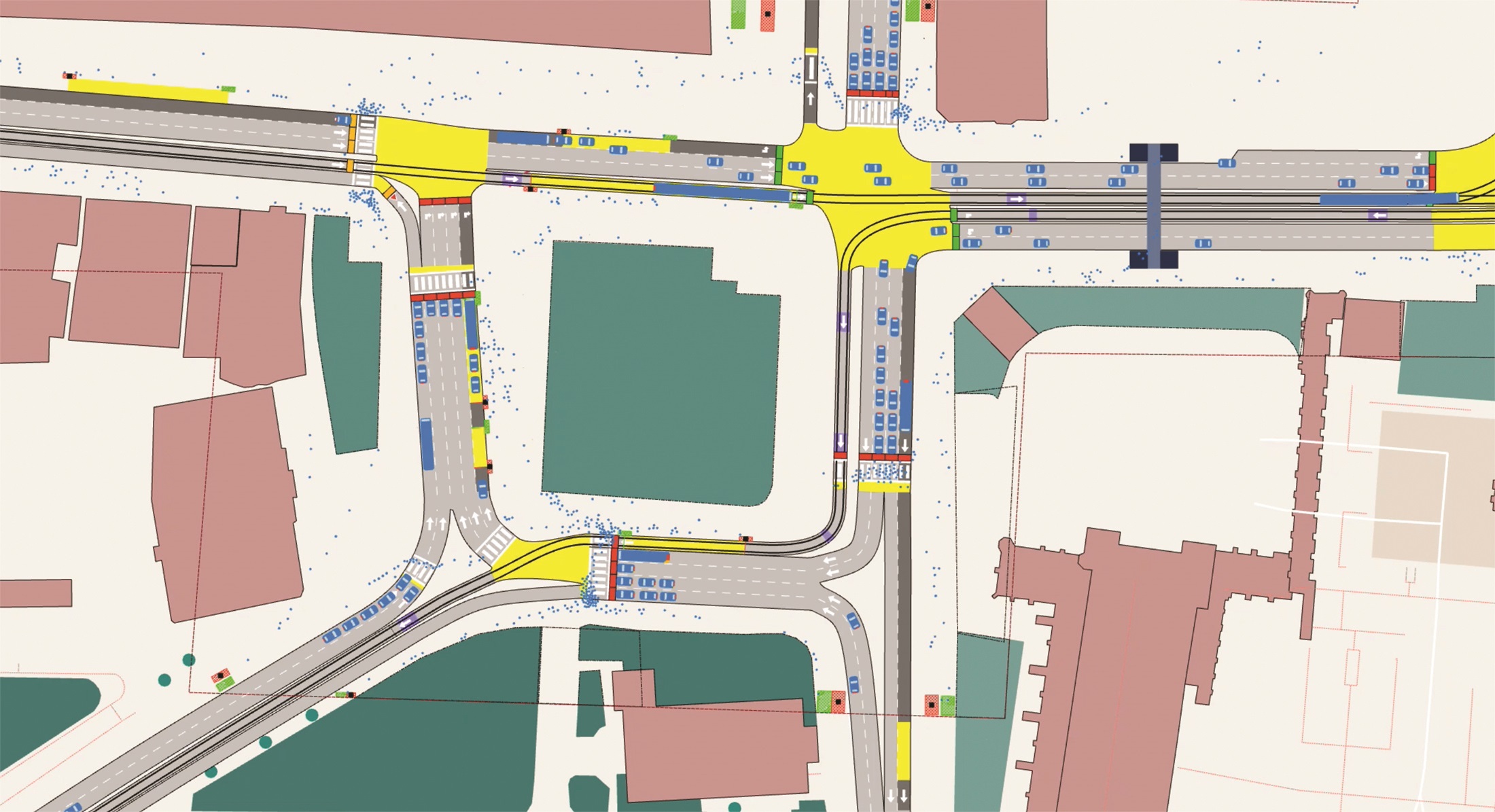

The afternoon was taken up meeting Transport for London's shared mobility teams at their central London HQ - a few miles through the busy city, around 30-40 minutes on a good day from Loud Mobility's offices in north London. This was exciting: the first time I've had to split venues at a course, with everyone invited to make their way to the centre of the city by any means of shared mobility they liked.

I was looking forward to the challenge. While I have used shared bikes in London for short journeys from time to time, I haven't really cycled since my own bike was stolen (in London) about a quarter of a century ago. The London Underground (Tube) and bus services are more than adequate for me to navigate the city. But this was a cast-iron opportunity to use shared bikes for a longer journey on unfamiliar territory.

So to be clear, I had fully intended to cycle: the London borough of Camden is home to Lime, Forest and Santander bike-share schemes so there's no problem finding one. So how did that work out for me, on the ground?

Listen to my tale of woe

The first bike I attempted to unlock was not working. Fair enough, this happens. The second worked but then seemed to indicate that I wouldn't be able to use it in central London. I can't remember the exact message which flashed up but it was enough to place doubt - utterly unwarranted, I'm now sure - in my mind. But I have fallen foul of geofencing restrictions on shared bikes in outer London before and wasn't taking any chances now that the clock was ticking.

The third was Santander - the friendly-looking red ones run by TfL itself. I've never used them but had downloaded the app ages ago. Only when attempting to unlock one did I realise I hadn't entered my payment details on the app. Getting out my credit card, finding my glasses so I could read the numbers, standing at the kerbside, holding my card and my iPhone together and not concentrating remotely on my surroundings in a bustling London street suddenly seemed like a bad idea.

I'm a middle-aged, streetwise Londoner: I know that phones are snatched frequently in the street - in fact, I've seen it happen. I've always impressed on my teenage daughter the need to be careful with her phone for this reason. Holding out my phone and debit card in one convenient package for any opportunistic, would-be robber seemed over-generous. I would have to tell the police how this happened; then come up with a convincing argument to my boss about why I really should be given a replacement phone; and finally, trickiest of all, explain to my daughter why she should carry on listening to me, despite evidence to the contrary.

By this point, time was beginning to press rather uncomfortably. I was frankly embarrassed at the prospect of being the Londoner on the course who would have either failed to turn up at TfL HQ, or would message to say he'd been taken to hospital, or would have to ask someone to 'talk him in'. My classmates were mainly continental Europeans who seemed to take to the idea of shared bike rides - even in a foreign city - as easily as breathing.

Reader: a confession. I did take shared transport to the meeting at Palestra House. Unlike most of my fellow attendees, however, I did not make the journey by bike. I reverted to my comfort blanket of the Tube network. I felt slightly ashamed.

The shame disappeared (embarrassingly) quickly as I reflected that, rather than fear of being knocked off my bike - eight cyclists were killed in London in 2023 and this undoubtedly informs my attitude to cycling in the city, too - my major danger was now the potential need to give up my seat to someone more deserving. I also knew exactly where I was going and how I'd get there.

As a compromise, I thought I'd arrive at Waterloo station, then enter my card details on the Santander app while sitting down in a safe, quiet spot, and then cycle the final few hundred metres to TfL HQ. However, at Waterloo, I couldn't get a phone signal, which meant I couldn't even access the app. I walked: at least this was active travel, I suppose.

So what have we learned?

The whole episode was a very, very instructive way of pointing out to me the street-practical issues involved in the on-page theory we had been discussing. Useful, to say the very least. I probably need to address my assessment of risk, and be better-prepared in future. Still, failure is good for the soul.

The afternoon with the TfL shared mobility team was a helpful insight into the work they do and the success they've had in increasing take-up in active travel. They were also candid about some of the frustrations involved. I also came away thinking how, given the regulatory, behavioural, jurisdictional, social and legal complications that London faces, its transport network as a whole actually works as well as it does.

Thanks very much to the Loud Mobility team for hosting, and to the Movmi team, especially Aoife Rafferty and Venkatesh Gopal - and of course to his predecessor as Movmi CEO, Sandra Phillips, who invited me to take part in the first place.

Leonardo da Vinci apparently said that 'learning never exhausts the mind'; this is probably why I left day 1 of the course feeling refreshed and stimulated.

(Also, I really need to take the plunge and cycle in central London. Thousands and thousands of people do it, perfectly safely, every day in big cities all round the world. It's time for me to get a grip).