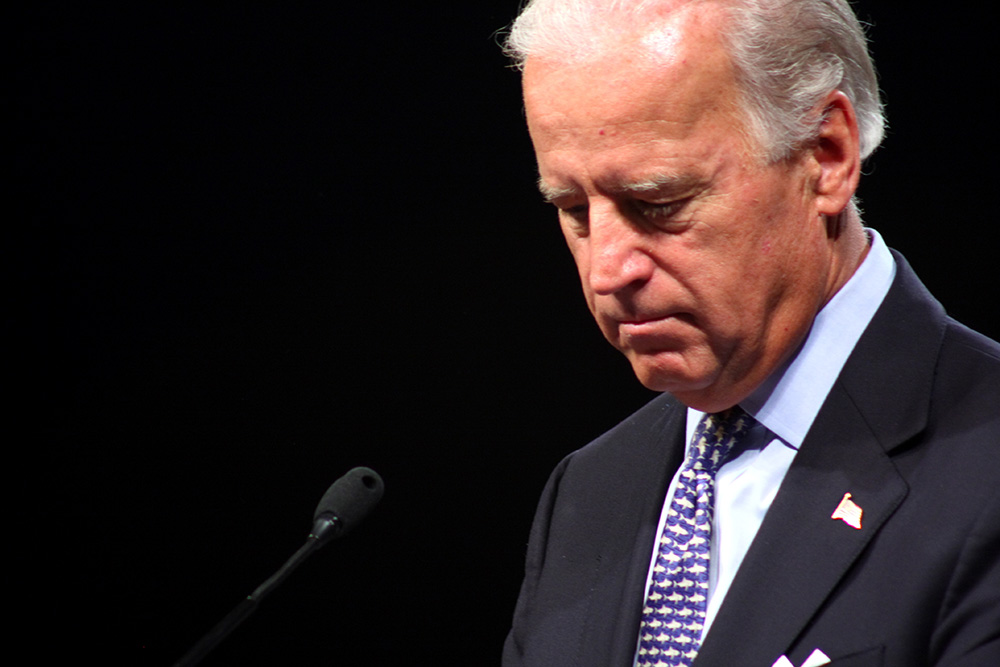

President Joe Biden has signed a $1.2 trillion infrastructure bill into law, which will include $110 billion of new investment in the US’s bridges and roads, $11 billion for transportation safety, $39 billion for public transit and $7.5 billion to boost the country’s electric vehicle charging network.

So what’s the problem? The problem is the lack of emphasis on public transport and active mobility. The Infrastructure Act fails to hit the mark in terms of meeting the needs not only for building back resiliency for public transport operators to get back to where we were in 2019, but to actually move the needle in terms of the modal shift that is necessary.

At the Cop26 climate conference in Glasgow, we heard of the need to double the usage of public transport in the next five to 10 years. So the US legislation fails on that front because only a small percentage of funding is allocated to public transport, if you look at the entire pie.

That shows you that the emphasis is really on an entire mix of different kinds of policy initiatives for physical infrastructure. They’re quite important, but the fact that so little spending is going to public transport - the mode that will have the most impact towards decarbonisation - just demonstrates how watered down it has become because of the corporate lobbies that have been influencing and affecting the outcomes of this bill.

Perpetuating the status quo

While it’s being hailed as a win for Joe Biden and Pete Buttigieg, if you look a little bit deeper in terms of the actual impact it’s going to have physically, environmentally and economically, it’s basically perpetuating the status quo because 30-35% of that budget allocation is going to roads and highways.

And this is really not even earmarked towards what is called ‘fix it first’ policy - meaning that you use the money to fix what’s in the ground right now – you don’t expand the physical infrastructure beyond that.

Also, the federal government has very minimal oversight on the actual decision-making at the local and regional state level, meaning that these monies are going to flow through the US Infrastructure Bill and be allocated in a very inconsistent manner by each individual state.

My home state of California, for example, may be more progressive and use its infrastructure funding to influence policies that support decarbonisation, climate and net neutrality; but you would have other states that could simply allocate that 30% of the pie towards building new roads - because there is no requirement for ‘fix it first’.

This means the US Infrastructure Bill falls short because a huge portion of that $1.1 trillion is going to go towards unsustainable highway building and urban sprawl. To reiterate, the bill promotes the status quo: it does not fundamentally change the structural fabric of US cities and it minimally addresses the needs of transport decarbonisation as set forth in climate policies and targets at Cop26.

Over-emphasis on EVs

But even Cop26 fell short, with its over-emphasis on electric vehicles (EVs), and virtual silence on active travel modes such as walking and cycling. In fact, the US Infrastructure Bill is a mirror image of what happened at Cop26. By this I mean: let’s double down on EVs; let’s just move people out of internal combustion engines into EVs - but we’re going to continue with urban sprawl, we’re just going to get into Teslas or into Rivian electric trucks. But these are still cars, these are still trucks: this is not shared mobility, and this is not active transport.

Moreover, if they cannot pass that reconciliation act for Build Back Better, which is the other piece of the legislative pie, then President Biden will simply not be able to match the mandate that he put forth on his election promise over a year ago.

In its original incarnation, the legislation had a healthy split of climate-facing initiatives that were reinforced by the Build Back Better Act; both of these two components reinforce each other to promote decarbonisation and modal shift. But because of the political jockeying on Capitol Hill, it fell short.

There’s another way in which Cop26 and the US Infrastructure Bill are related: in Glasgow there was a lack of emphasis on active travel too.

Which lobby is going to have the lion’s share of the voice and the influencing in terms of policymakers and outcomes? It is going to be the automotive industry and other well-funded enterprises that are looking to align with the corporate sustainability goals that are required by their shareholders and the public.

Near silence on active travel

That’s why the Teslas and the Rivians and the Fords are getting a lot of press in terms of the electrification of their fleets and how they can contribute to sustainability; but there is a very minimal presence from the bicycle lobby and there’s an even smaller pedestrian, active transportation lobby.

At least public transport had a voice at Cop26: I’m a big supporter of UITP and they both presented at Cop26 and submitted an open letter discussing the importance of public transport in decarbonisation. However, they were given a very minimal slice of the pie - but even that was more substantial than what the cycling and pedestrian lobby got, which was near-silence.

In fact, it was only a global campaign led by the European Cyclists’ Federation (ECF) that helped to get a last-minute recognition of active travel in the official declaration published at the Cop26 Transport Day on 10 November. It protested the near-exclusive focus on EVs and total absence of active mobility.

The Cop26 declaration eventually read: “We recognise that alongside the shift to zero-emission vehicles, a sustainable future for road transport will require wider system transformation, including support for active travel, public and shared transport, as well as addressing the full value chain impacts from vehicle production, use and disposal.”

ECF admits that this small reference is a far cry from what’s needed to cut transport emissions and reach climate goals, but says it can be built upon at Cop27 in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt.

“The addition of walking and cycling in the Cop26 transport declaration is a small but important first step,” said ECF president Henk Swarttouw. “For the next step, signatories of the declaration will have to put their money where their mouths are and invest in significantly boosting cycling levels.”

This marginalisation of active travel and public transport is seen on both sides of the Atlantic, with the US Infrastructure Bill and Cop26. More work needs to be done in the Build Back Better act and at Cop27 in Egypt next year to place greater emphasis on the role shared mobility plays in decarbonisation and meeting our near-term sustainability goals.

Anything less is a missed opportunity, for the planet.

About the Author:

Scott Shepard is VP of global public sector at Iomob