The technology developed for vehicle automation can (and already does) save lives on the road – which has to be celebrated - and if the decision about licensing driverless vehicles (DVs) is left to departments of transportation worldwide, then green lights are a certainty.

However, the impacts of DVs will not be confined to the roads: they will resonate throughout society and spread well beyond the brief of any single governmental department. Strange, then, that a comprehensive evaluation of the technology’s impact appears noticeably absent.

Research and statistics regarding the impact of automation are available and can be used to assess the wider implications. Coupled with other research they can give an idea of the impact DVs will have throughout society and reveal some disturbing implications that could see countless lives ruined and premature deaths increase.

Before dismissing such thoughts as ridiculous, take time to consider the ‘bigger picture’ using available statistics and research.

Initial claims were that DVs will prevent more than 90% of crashes and therefore the death toll will reduce to almost zero as the manually-driven fleet declines. That claim did not stand up to analysis by safety expert Alan Thomas who calculated crash reduction will be less than 50% (ITS International March/April 2017), although any reductions are to be welcomed.

Road deaths

According to the World Health Organisation, global road deaths exceed 1.3 million annually (half being pedestrians or cyclists) and are the biggest killer of five to 29-year olds.

It also points out that road safety levels vary enormously around the world and more than 90% of road traffic deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. Many of these have not adequately addressed the major contributory factors for fatal crashes: speeding, alcohol use, not using motorcycle helmets and seatbelts, distraction, unsafe roads and unsafe vehicles.

Countries that have addressed these issues have far fewer road deaths, including Great Britain which has one of the lowest rates of road deaths in the world at about 3.1 fatalities per 100,000 population. Even so, 1,752 people died on UK roads in 2019.

But removing the driver is not the only option for deploying safety technology and while DV advocates may want to confine the debate to road safety, the wider implications have to be considered, starting with ‘driverless’ – a word that big business studiously avoids.

Financial incentive

For transport companies in developed countries, paying the driver is usually their biggest running cost. Therefore the financial incentive to adopt DVs will be enormous - particularly as one DV can replace up to three drivers and possibly more than one vehicle. Cutting running costs is the big prize and any reduction in road crashes is a bonus – the loss of jobs may be seen as somebody else’s problem.

While vehicle manufacturers, financiers, research establishments and business operators can ignore the fate of displaced drivers, governments and societies must assess and address this issue before allowing the sale of DVs.

The UK, for example, has 411,000 taxi and private-hire vehicle drivers, 600,000 HGV drivers, four million vans on its roads and there are 114,000 bus and coach drivers in England alone. Therefore, in total the UK has more than five million jobs that require driving and one survey estimates a million of those could be lost to automation.

Driving as a living

A recent study by the UK’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) assessed the risk of jobs lost to automation across England. In a table of 370 employment categories, it ranked van, taxi, truck and bus/coach drivers as the 17th, 31st, 43rd and 51st jobs at highest risk of automation, with probabilities of 65.5%, 63.4%, 62.2% and 61%, respectively.

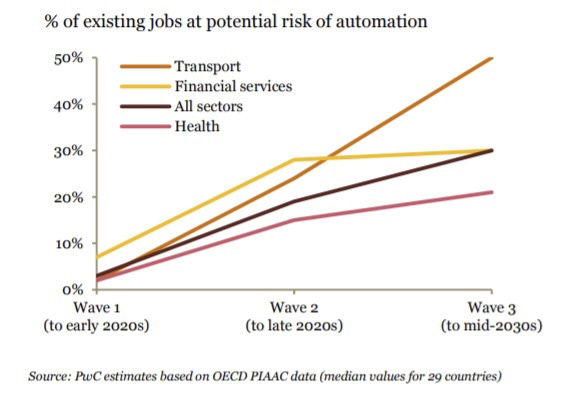

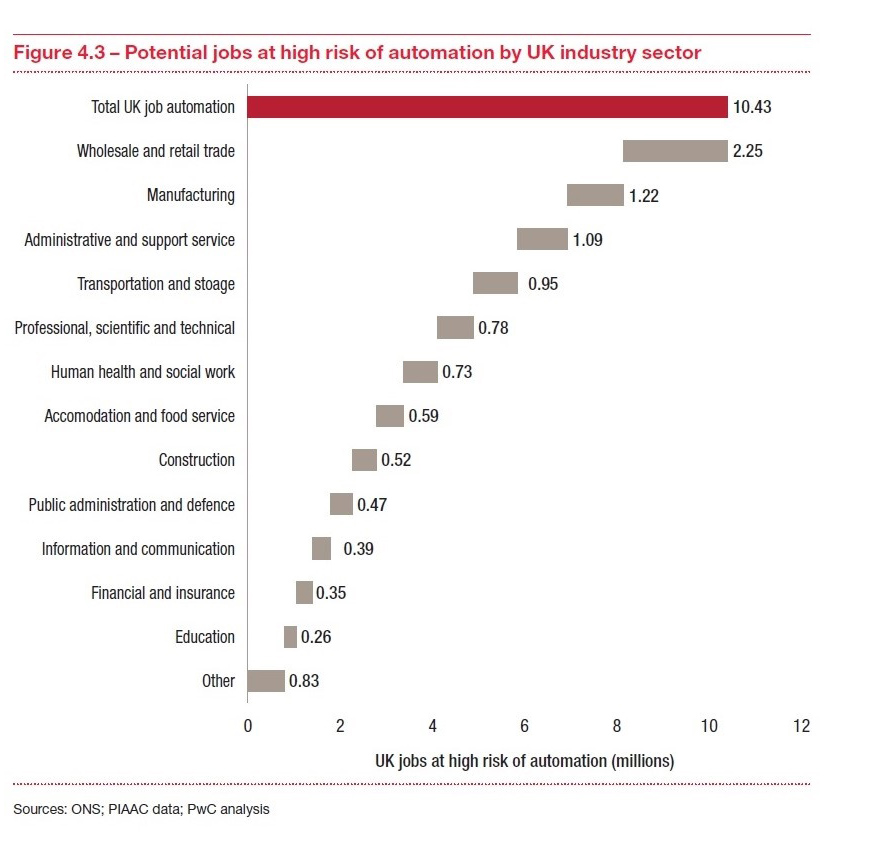

PWC’s 2017 multinational study concluded the transport sector will see the highest rate of automation-related job losses with half of the jobs disappearing by the mid-2030s. In the UK it predicts up to 30% of all jobs (more than 10 million) are at high risk of automation and the highest of all are transport jobs, 56% of which will disappear with 950,000 people losing their livelihood.

Of course, not all of the transport sector jobs lost to automation will be drivers and driving is not the only task many of the employees undertake, so the job losses will not be uniform. For example, DVs cannot collect or deliver letters and packages to individuals in their homes or offices, nor can they help people with disabilities into and out of taxis or buses.

So realistically, how many drivers would taxi firms need to retain to cover situations such as passengers with disabilities? Perhaps 20% - which means 80% of drivers could be laid off.

Across the UK that would equate to 328,000 job losses.

Echoing the ONS findings on truck drivers is research from the US which concluded that (despite apparent driver shortages), between 50% and 75% of drivers could be replaced by DVs. If applied to the UK it equates to between 300,000 and 450,000 job losses.

For reasons already mentioned, only a minority of van drivers would be replaced by DVs although even if 10% of them were laid off that could equate to 400,000 lost jobs. The impact on bus and coach drivers may be minimal as there are public confidence and service (stowing/unloading) aspects to these jobs, although the driver may become a DV minder/passenger assistant.

This gives a total of around one million, roughly echoing PWC’s estimate.

Given that Ford is expecting to launch a driverless car in 2022, PWC’s linear timeline of job losses stretching to the 2030s seems unlikely as businesses adopting DVs early could undercut those still using drivers.

This could prompt a fleet renewal race that would accelerate the rate of job losses, perhaps halving the usual fleet renewal times to three years, then (using PWC’s prediction) the pace of job losses would be 316,000 per year with, let’s say, 90% (285,000) being men.

Employment prospects

If the prospect of a million drivers losing their livelihood isn’t bad enough, the statistics about what can happen to the unemployed is chilling.

In its report Men and Suicide, UK-based support group The Samaritans, states: “There is a well-known link between unemployment and suicide. Unemployed people are 2-3 times more likely to die by suicide than those in work.”

Furthermore, most of those replaced by DVs will be low-skilled individuals who face the greatest difficulty in getting another job and ONS figures show unemployed low-skilled workers are at a 44% higher risk of suicide.

Although the reasons behind each suicide are varied and complex, with 10 million other low-skilled people losing their jobs to automation at the same time, that may be an underestimate.

Historian Yuval Noah Harari believes automation will cause mass unemployment of unskilled workers and could herald the creation of what he calls The Useless Class, leading to potential civil unrest.

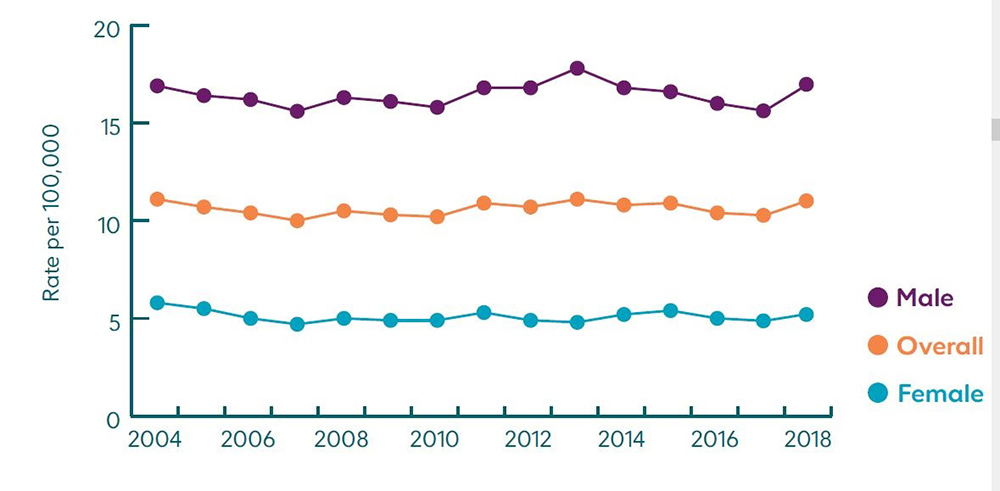

Suicide is already the biggest cause of premature death for those between the ages of 10 and 34 for women and 10 and 49 for men, according to Public Health England. Road deaths rank second, third and below fifth in the various age bands.

The UK recorded 6,507 suicides in 2018 - three and a half times the number of road deaths and three-quarters of the victims (4,903) were men. Male suicide peaked at 27.1 per 100,000 between the ages of 45 and 49 – that’s almost nine times the rate of road deaths.

Following the 2008 economic recession, a study by Coope, Gunnell, Hollingworth et al (2014) concluded that a 10% increase in the number of jobless males creates a 1.4% increase in suicides.

Due to the cause and nature of the 2008 recession, this must be considered an average figure and as low-skilled workers are at a 44% higher suicide risk, that figure could be above 2%.

Before the Covid-19 pandemic, 746,000 men in the UK were registered as jobless. In the scenario above, an additional 285,000 males would become unemployed - a 38% rise – for which Coope, Gunnell and Hollingworth would expect a 5.3% increase in male suicides or an additional 260 deaths. If the ONS is correct about low-skilled workers’ suicide risk, then the additional death toll could top 370.

On that basis, the introduction of driverless vehicles will lead to more deaths (combining on and off the road) than would otherwise be the case.

All these additional deaths are avoidable as the road safety technology developed for DVs can be fitted in manually-driven vehicles.

DVs’ other problems

DVs will reduce road efficiency. Robin Chase’s Heaven or Hell scenario sees empty DVs being sent home to take children to school or collect groceries or even circling while the owner is in a meeting.

Numerous studies have concluded DVs will increase vehicle miles travelled (VMT) and at the 2019 MaaS Market Conference, Dallas Area Rapid Transport’s Gary Thomas raised the prospect of vehicle occupancy rate actually falling below one.

Circling ride-hailing vehicles show how easily traffic congestion is amplified – not that this will concern venture capitalists and vehicle manufacturers or even DV users who can utilise the journey time to work or make phone calls. However, for pedestrians and other road users, local residents and the environment, such congestion will be intolerable.

There is also the potential misuse of DVs for terrorism. A DV could take a miscreant to the airport before heading downtown with a ticking payload in the boot - as accurate as an Exocet at a thousandth of the cost.

I have questioned government officials from three continents about this deadly potential, and none has suggested viable counter measures. Most say ‘extremists can already drive [the bomb] there themselves’ while ignoring the potential for many less motivated terrorists deciding to act because they do not need to put their own lives at risk.

This is no theoretical scenario. In July 2019 a UK-based Iraqi national, Farhad Salah, was sentenced to 15 years in jail for plotting to use a driverless car to carry a bomb.

UK authorities alone list more than 3,000 terror suspects and there have been up to five major terror attacks per year, with car or van use featuring in several more recent incidents with the perpetrator(s) either being killed or arrested in each. How many more potential terrorists would act if they can be miles away from the scene (or on an aircraft) and deliver their deadly payloads remotely?

Win-win alternative

It doesn’t have to be this way.

Using the technology developed for DVs in advanced driver-assistance systems in manually-driven cars will alert drivers to a hazardous situation or take control to avoid/mitigate an impact. In many high-income countries such systems will soon be mandatory for new cars.

This approach will achieve the lower road crash and fatality rates without enabling empty running. It won’t provide a bomb-carrying system for terrorists, nor will it increase VMT and journey times.

It would also keep millions of drivers (worldwide) gainfully employed and paying tax rather than claiming benefits. The only losers (or more accurately non-gainers) would be city financiers, vehicle manufacturers and some transport companies.

While governments must consult on these topics, public transit expert Jarrett Walker warns: “There is an enormous venture capital budget to shape the debate, to steer policy in a direction that is profitable.”

The safety smoke screen created by vested interests must not be allowed to blind or divide governments - or close down the full debate societies must have about the long-term effect and unintended consequences of DVs.