The more you know about traffic analysis, the more careful you’ll become about reforming traffic analysis methodology. The more you know about intersection design, the more timid you’ll become about innovative intersection design.

It’s human nature to mentally codify something as you become more familiar with it. There are times when the best way you can up your professional game is to embrace sheer ignorance.

‘Applied ignorance’ is a significant part of my career, so I’m always happy to hear about others who have experienced some form of success by similar means. I’m a sucker for behind-the-scenes stories about my favourite movies, screenwriters, and directors.

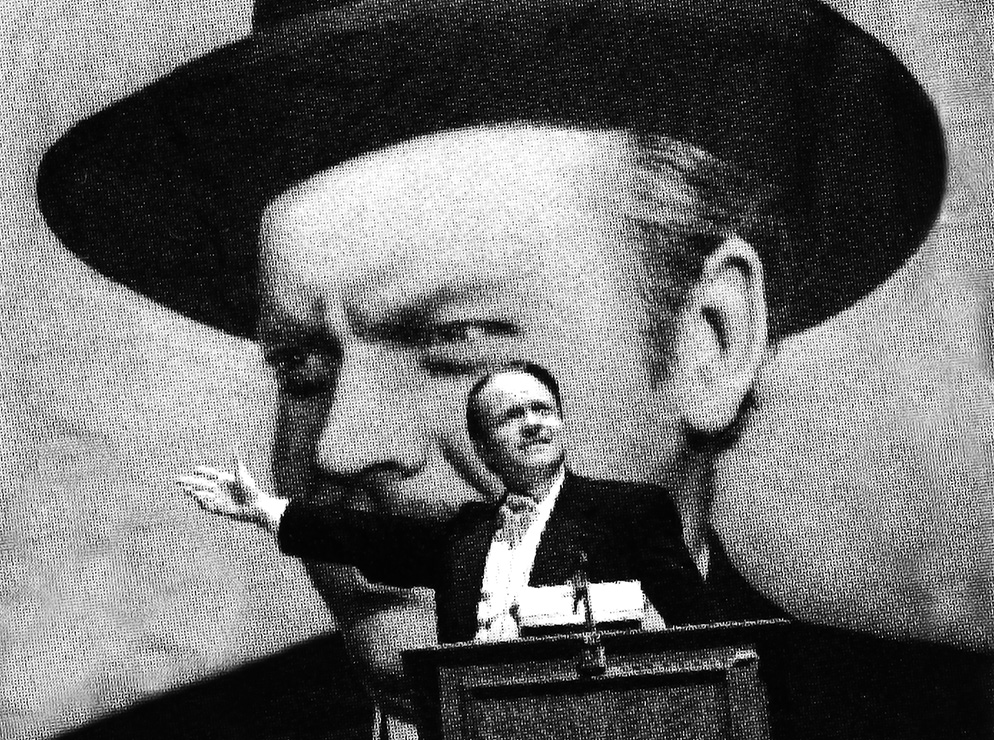

Legendary film critic Roger Ebert used to say Citizen Kane was the greatest film of all time and there could be no competitor. Hundreds of polls and articles have been published over the years sharing Ebert’s opinion. ‘Innovation’ is the short answer to why Citizen Kane is so revered. The storytelling techniques, emotional soundtrack, and morally complex characters transformed the way future writers and directors approached filmmaking.

This was director Orson Welles’ debut film, and he was only 24 years old when he was crafting the masterpiece. Twenty years later, he sat for an interview with BBC Monitor. Here’s one of many insightful segments.

Orson Welles: I didn’t want money. I wanted authority. And after a year of negotiations, I got it. My love for films began only when we started work.

BBC: What I’d like to know is where did you get the confidence to—

Welles: Ignorance. Sheer ignorance. You know, there’s no confidence to equal it. It’s only when you know something about a profession, I think, that you’re timid or careful.

BBC: How does ignorance show itself?

Welles: I thought you could do anything with a camera that the eye could do, or the imagination could do. And if you come up from the bottom in the film business, you’re taught all the things that the cameraman doesn’t want to attempt for fear he will be criticised for having failed. In this case I had a cameraman who didn’t care if he was criticised if he failed, and I didn’t know that there were things you couldn’t do. So anything I could think up in my dreams I attempted to photograph.

BBC: You got away with enormous technical advancements, didn’t you?

Welles: Simply by not knowing that they were impossible. Or theoretically impossible.

I’m no Orson Welles, but I’m great at asking big and/or dumb questions about topics that I have no expertise in. And similar to Welles, colleagues have attributed confidence to something that’s just ignorance. Asking big ‘why’ and ‘what if’ questions is so unusual in professional planning and engineering, because these are industries with established processes and structure.

- Car lane width: if AASHTO allows 10 feet, why do I keep using 12 feet?

- Bike-lane width: why aren’t two-way bike lanes wide enough for two bikes to pass each other without clipping their handlebars or elbows?

- Sidewalk width: why aren’t downtown sidewalks wide enough for two people to walk side-by-side as someone approaches them?

- Signal timing: is there a way to time a corridor so as not to encourage speeding between intersections?

- Roundabout diameter: why are we designing for optimum speed instead of optimum safety?

- Streetlight type and spacing: why do downtown streets use highway-style lighting instead of pedestrian lighting?

- Design speed versus operating speed: what if we didn’t design the road for motorists to comfortably drive 10mph faster than the posted speed limit?

Innovating from within the status quo

It’s not flattering to be called a conformist, so none of us will put that in a bio. Where’s the excitement or pride in that, right? “Hi, my name is Andy, and I’m just like everyone else.” Day-to-day, transportation planning and engineering has a framework that consultants and clients work within. So while some will always be on the fringe of the industry, there is a status quo that will be maintained. And that’s fine.

It’s absolutely possible to innovate an industry from within the status quo. Orson Welles did it. Welles didn’t abolish filmmaking while coming up with new techniques and styles for visual storytelling. His end goal was the same as any other director: tell a memorable story that will entertain the audience. It just so happened that he didn’t let himself be handcuffed by the status quo methodology of his peers.

Example 1: What if technology helped agencies talk to each other?

Transportation data has traditionally been managed using centralised databases or proprietary software systems that are not easily interoperable with other systems. This makes it difficult to share data with other stakeholders, collaborate on transportation projects or make data-informed decisions.

Blockchain technology is a decentralised and distributed ledger system that allows for secure and transparent data storage and sharing. You could create a secure and tamper-proof system for managing transportation data that can be easily shared with other stakeholders, regardless of the specific software or systems they’re using. Blockchain could have a number of benefits for traffic engineering, if we even think to ask the questions.

For example, a traffic operations centre can use blockchain-based systems to securely store and share traffic data with emergency responders and local agencies, improving coordination during incidents or emergencies. Obviously, that would help reduce the risk of traffic disruption and improve public safety.

Example 2: What if transit payments were finally secure?

A benefit of blockchain technology in transit operations is the ability to create a secure and efficient payment system that can be used across different transit services and platforms. Anyone working in transit planning knows what a headache it is dealing with multiple incompatible systems. A blockchain solution could help streamline the payment process for riders and reduce the cost and complexity of managing payments for transit operators.

For example, a city bus service could use blockchain-based smart contracts to automate collecting fares and distributing payments to different transit operators. Riders could pay for their fares using a digital wallet linked to their blockchain account. The smart contract would automatically verify the fare payment and distribute the appropriate amount of funds to the different transit operators involved in the rider's journey.

Another potential application of blockchain technology in transit operations is creating a tamper-proof system for managing transit data. This could transform real-time data on ridership, vehicle performance and other key metrics.

Example 3: What if we told different stories?

Data privacy is one of the key challenges facing Mobility as a Service (MaaS). Or is it? Maybe our lack of compare-and-contrast storytelling is the problem. I don’t think it’s the acts of collecting and monetising data that keep MaaS in the shop. How do you explain the mainstream adoption of TikTok? Consider a typical reaction to zero-dollar social media versus zero-dollar transportation (the idea that you could allow the data your car produces to be sold in return for a reduction in the price of buying the vehicle):

"We want to track everything you do and say and type on all your devices in exchange for showing you videos."

"Oh it’s totally worth it. I can't believe this is free!"

"We want to track your car's sensors in exchange for a free car."

"Get out of here with your Big Brother schemes!"

As transportation providers collect more data on riders, including their travel patterns and payment information, there’s a growing concern about how this data will be used and who will have access to it. Many Americans are understandably sceptical or wary of monetised data, particularly in the wake of high-profile data breaches and scandals.

MaaS providers are going to have to ensure that the data they collect is protected and used in a transparent and responsible manner. This may involve implementing strong data security protocols, such as encryption and multi-factor authentication, to protect sensitive information from unauthorised access. It may also involve adopting data privacy policies that give riders more control over their personal information, such as the ability to opt out of data collection or choose how their data is used and shared.

MaaS may work better under business models that prioritise data privacy and user control. For example, rather than monetising user data through targeted advertising, MaaS providers could offer premium services or subscriptions that allow riders to access additional features or benefits without sacrificing their privacy.

But above all else, what if we got in the habit of connecting the dots for the travelling public? I’ve conducted a fair share of unscientific polls about Big Data, and I have yet to hear someone tell me they’re aware of how the social media apps on their phone collect, share, and sell user data. There’s a huge knowledge gap when it comes to Meta (Facebook and Instagram) and TikTok. I keep hearing “I just don’t want to know.”

Americans are perfectly willing to trade their data for something “free.” One opportunity for transportation professionals is to compare/contrast the type of data collected for integrated mobility and mindless videos.

Now what?

Practise some applied ignorance in your professional career. Humbly ask questions knowing you don’t know what you don’t know. The worst thing that happens is you learn something new about a topic. The best thing that happens is you spark a conversation that leads to a policy or infrastructure improvement.

About the Author:

Andy Boenau is a writer, filmmaker, podcaster, and consultant in the mobility industry https://urbanismspeakeasy.com