London’s newly-expanded ULEZ is big. Really big. Said to be the largest in the world, it has grown far beyond its urban core to the edges of its suburban crust.

The £140m expansion at the end of August saw the zone more than quadruple from 380km2 (147 sq miles) to 1,579km2 (610 sq miles), encompassing all 32 London boroughs. The zone now encroaches close to the city’s orbital M25 motorway at most compass points, covering 8.8 million residents and including the city’s main air hub, Heathrow.

The expansion has been, to put it mildly, a turbulent one. It’s fair to say that a significant minority of Londoners oppose the scheme (although according to one poll, not most of them). A few took criminal action against the imposition of the £12.50 daily charge payable by owners of non-compliant vehicles, vandalising hundreds of enforcement cameras in the expanded zone. Many thousands more (one UK paper claims up to two million) attempted to defeat ANPR cameras with reflective ‘stealth’ tape.

“Beyond the political pantomime, is there merit in the criticisms of the scheme’s expansion?”

Confusion about the zone’s new borders, patchy implementation of the infrastructure to police them and a simmering political furore all further clouded the expansion.

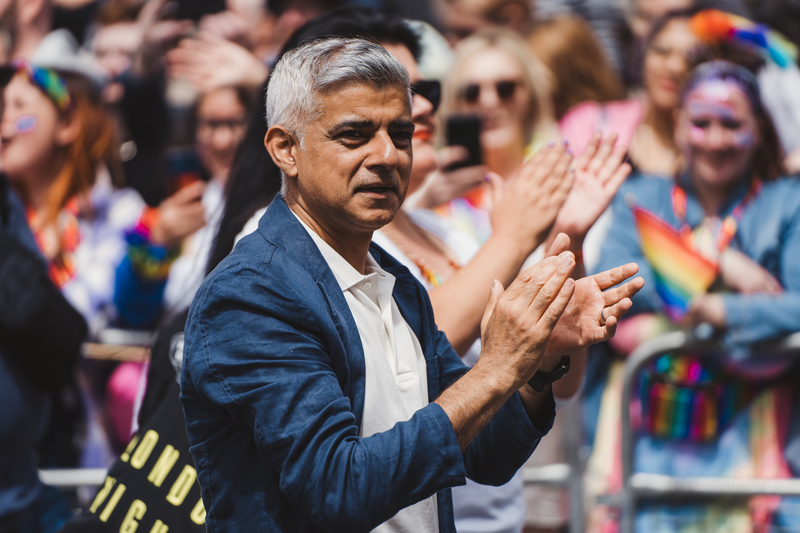

Opposition has been fierce. Four councils (run by the UK’s Conservative party, which also forms the national government) have unsuccessfully fought the scheme’s expansion through the courts: Hillingdon, Harrow, Bexley and Croydon. The (Conservative) UK prime minister Rishi Sunak weighed in against (Labour) London mayor Sadiq Khan’s ‘war on motorists’ (omitting to mention that it was a Conservative London mayor, Boris Johnson, who originally initiated plans for a London ULEZ).

ULEZ as a political football

There is a wider context here. Feeling the political heat, the Conservative party of government – facing defeat in 2024’s general election if the polls are to be believed - senses political capital to be made in slowing and even reversing plans to limit car use, rolling back low-traffic neighbourhoods (LTNs), fighting the expansion of 20mph urban speed limits, delaying controls on the most polluting vehicles and slowing the phase out of fossil fuel burners.

The fact that the Conservatives retained one Parliamentary seat in a recent by-election (the London borough of Uxbridge, ironically the seat formerly held by Johnson himself) is - in part at least - owing to its residents’ anger at the ULEZ expansion.

Beyond the political pantomime, is there merit in the criticisms of the scheme’s expansion?

What are the arguments against ULEZ?

Too many vehicles will be penalised

Organisations including motorist membership group the RAC have challenged TfL’s claims that more than 95% of vehicles in the zone are compliant – and, by implication, the suggestion that only a few laggards will be penalised by the scheme. The RAC claims that in fact more than 850,000 vehicles will not be compliant - one in six cars. The Office for Statistics Regulation (OSR) has criticised TfL for lacking transparency about the data supporting this claim.

Less affluent workers are being unfairly penalised

The ULEZ penalty hits car-dependent people towards the bottom end of the income scale, who cannot afford more modern, cleaner vehicles. To address this, a £160m scrappage scheme offers up to £2,000 for scrapping a car and more for small business owners who run commercial vehicles. This only applies to Londoners, however, and not to affected residents outside the city who travel regularly into the capital.

The scheme is a mayoral tax grab

Estimates of the fines levied on non-compliant vehicles range from annual totals of £260m to £400m a year. Both figures are more than annual council car parking penalties nationwide and they serve as a useful benchmark – a recent Freedom of Information (FOI) request found London’s smaller, pre-2023 ULEZ zone generated over £224 million in 2022. TfL rejects criticisms that the scheme is a ‘cash grab’ by Khan to do with as he wishes, pointing to the fact that all revenues will be reinvested in London’s public transport network. Critics will seek reassurance that this will happen. TfL forecasts that the LEZ/ULEZ scheme will generate net proceeds of under £200m per year for the first two years with declining net proceeds thereafter as Londoners' vehicles increasingly come into compliance.

Alternative transport options don’t exist

While ULEZ revenues may be hypothecated to pay for mass transit improvements, addressing transit in the city’s outer suburban edges will take time and in many cases will not achieve what private cars can in terms of connectivity. London’s highly suburban outer boroughs lack the dense public transport networks of the city’s centre, with patchier tube and bus coverage, for example. Will investment help address public transit options outside the zone’s immediate boundaries?

ULEZ expansion will hardly impact air pollution levels

The primary goal of the ULEZ is to reduce harmful air pollutants, particularly nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and particulate matter (PM2.5 - the fine particles emitted by cars, industry and other harmful sources), which have been linked to respiratory and cardiovascular health problems. TfL points to the fact that since in the initial phases of the ULEZ’s introduction, pollution levels in London have dropped significantly, by more than 50% in some areas.

But the newly-expanded zone will have much more modest impacts, according to the mayor’s own impact assessment, which predicts a reduction of 1.3% in the average Londoner’s exposure to NO2 and negligible reductions of 0.1% in exposure to particulates. According to calculations by the UK’s Channel 4 News, spread across the city’s population, expanding ULEZ to outer London adds just 0.0089 days – or 13 minutes – to the average Londoner’s life expectancy this year.

Despite the above criticisms, Khan is unrepentant and can point to some stark statistics that support the need to tighten air quality standards further still. Even with the expanded ULEZ, it is estimated that no Londoners will live in areas that meet the tough new World Heath Organisation annual average guidelines of 10 microgrammes per cubic metre of air for NO2 or 5 microgrammes per cubic metre of air for PM2.5.

Beyond London and the UK, there are lessons in London’s ULEZ expansion for other mayors and major municipalities in Europe in particular - who will be aware of the sobering fact that London’s air was already relatively clean compared to many European cities.

“City mayors must carefully weigh the costs of ULEZ expansion alongside the costs of poor air quality”

An investigation by German broadcaster Deutsche Welle (DW) using satellite data from the Copernicus Atmospheric Monitoring Service (CAMS) found that in 2022, 98% of Europeans lived in areas where PM 2.5 levels were over WHO limits.

Pollution was especially severe in parts of central Europe, the Po valley in Italy and in larger metropolitan areas, such as Athens, Barcelona and Paris with the most polluted reaching annual averages of PM 2.5 of around 25 micrograms.

According to a study published in science journal The Lancet using pollution data from 2015, around 10% of deaths in cities like Milan could be prevented if average PM 2.5 concentrations dropped by 10 micrograms per cubic meter.

And if Europe's major cities were able to hit the five micrograms per cubic meter target, the researchers concluded there would be 100,000 fewer pollution-related deaths every year.

Expanding a city ULEZ beyond a core area is, however, clearly fraught with complexity and is hostage to considerable opposition. Those wanting to expand their own zones might consider the following:

Focus on the ‘why’

Imposing ULEZ zones based on carbon emissions or Net Zero arguments is likely to have less appeal across a city’s electorates - and especially its drivers. The political arguments for imposing limits on these grounds are at the least contested and in some cases are being rejected.

It may be better to focus on the very well-evidenced impacts of poor local air quality. Car drivers are quite capable of grasping that using their vehicle imposes externalities on all and that cleaner air is in their interests too, but this messaging can get lost.

The pernicious – and very well-documented - impacts of poor air quality need to be driven home – such as particulate matter’s ability to be absorbed into the bloodstream and even into the brain stem.

The social and business implications of this need to emphasised - workers are estimated to be 5%–6% more productive when air pollution levels are rated as good, and greater exposure to fine particles is associated with lower intelligence and diminished performance over a range of cognitive domains.

Air pollution impact on cognition among the young is another powerful argument. The implications for city schools located close to busy roads where traffic air pollution peaks when children are at or travelling from or to school are obvious. Studies show children from highly-polluted schools have smaller growth in cognitive development than children from less-polluted schools.

The economic and political context matters

The furore over the London ULEZ expansion was so intense in part because of the financial pressures on working people during a cost-of-living crisis. The imposition of restrictions on movement, however well-justified and proportionate, require some level of assent from those who experience them and support to help them upgrade vehicles.

Assess the trade-offs and opportunity costs

Could the capital (both financial and political) invested in London’s ULEZ expansion have been better directed to achieve air quality improvements elsewhere? Road traffic is not the only contributor to poor air quality. London’s Underground network - where PM2.5 concentrations are approximately 15 times greater than in the surface and roadside environments in central London - is one area of focus that critics claim is being ignored. Air quality improvement measures here would seem an important priority – would money be better spent on these rather than on relatively modest improvements in the outer boroughs? Closer econometric study here might provide clearer answers.

Consider alternative, cheaper measures

City-wide ULEZ enforcement is costly and not every city will be able to afford the infrastructure to encompass the city beyond a core area. Other measures may be able to achieve similar aims for less. One such is emissions-based parking (EBP), which targets higher-polluting vehicles when they park, instead of charging a one-off toll when they pass a certain point. Simplicity, fairness to all vehicles – including ones inbound from beyond an ULEZ - and cost-effectiveness are arguments for it. The fact it enforces and encourages - rather than forces - cleaner vehicle adoption is a further benefit. EBP, for example, led to a 16% reduction in polluting vehicles when introduced by London’s Westminster City Council in 2017. The scheme has now been adopted by almost half of London boroughs.

Complex calculations

“There are no solutions, only trade-offs,” wrote economist and commentator Thomas Sowell. City mayors must carefully weigh the costs of ULEZ expansion (financial, political and economic) alongside the costs (in human lives and stunted productivity) of poor air quality.

These are complex calculations, but they must be done. Where the predicted air quality improvements for ULEZ introduction or expansion are modest and the costs high, city halls might do well to consider alternatives that may achieve more for less while imposing fewer restrictions on movement - and also lowering the political heat.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR:

Andrew Stone is a freelance writer on transport and urban mobility issues