The US Federal Communications Commission (FCC)’s recent revamp of how the 5.9 GHz safety spectrum is used can politely be described as ‘controversial’. ITS America went further, calling it ‘reckless’.

It is certainly a major change: as well as making new spectrum available for unlicensed services such as WiFi, FCC is giving up on “long-stalled” dedicated short-range communications (DSRC) technology in favour of cellular Vehicle to Everything (C-V2X). The FCC’s line is simple: 5.9 GHz has been designated for DSRC for over 20 years. In that time, “deployment has been painfully slow, and as a result, DSRC has done virtually nothing to improve automotive safety”.

C-V2X, on the other hand, shows great promise, “which is why automakers here and around the globe are turning the page on DSRC and moving to implement C-V2X”. So, DSRC hasn’t worked, let’s try C-V2X instead.

US technology firm Applied Information caused a stir late last year when it made an interesting offer: on the basis that dedicated DSRC roadside units (RSUs) will soon be obsolete, it offered to buy back installed DSRC technology from US departments of transportation, thus offsetting the cost of upgrading to C-V2X.

At the same time, Applied announced the availability of full C-V2X-connected vehicle RSUs and on-board units (OBUs) with an automatic upgrade to 5G NR when the technology becomes available.

Applied says the new units provide both C-V2X Direct and Network (4G LTE) connectivity, enabling short-range and long-range communications, and making them suitable for applications such as emergency vehicle pre-emption, transit bus priority, red-light running alarms and school zone speed warnings. The units are also configured to be upgradable to new cellular technologies such as 5G and 6G.

Applied boss Bryan Mulligan, a former civil engineer from South Africa, has been in the US for the past 25 years – and is a serial entrepreneur. “The last time somebody else worried about my salary, I was in my mid-20s,” he laughs over a Zoom call from his company’s Infrastructure Automotive Technology Laboratory (iATL) in Georgia (more of which later).

Preconceived ideas

Three things strike you about the firm’s buyback offer: it’s bold; it has the air of good sense about it; and it is a phenomenal marketing opportunity. Mulligan does not demur.

“This is the time to be bold,” he says. “America is the best place in the world to build a business: people buy stuff; entrepreneurs are respected. But the interesting thing is that the transportation business is run by the government: the Federal, the state, counties, the cities, the towns - and that makes it a little bit more difficult for an entrepreneur. The only way we’re going to deploy connected vehicles (CVs) is by private sector innovators taking a larger role and leading.”

Mulligan admits to having had preconceived ideas about the FCC’s approach to the spectrum – and admits that he was wrong. “One of my dad’s expressions was ‘when your argument’s weak, shout like hell!’” Mulligan laughs. “And to a certain extent, all of us in transportation are actually being a little bit guilty of that: if it’s not going our way we just increase the amplitude of our arguments - not the rigour of arguments.”

He argues that when CVs were first proposed, “it was really the only game in town: we were going to have radios in all the vehicles and this was going to stop vehicles running into each other – and the idea wasn’t really any more sophisticated than that”.

Meanwhile, technology moved on. Automotive radars “suddenly became a thing, they’re on every car”. Since radars can prevent forward collisions, Mulligan suggests this has removed “a big use case” for CVs: “Now you don’t need radios in both cars you can do the primary functionality of CVs with radios in one car.”

He admits to being provocative but suggests that those who are committed to DSRC aren’t giving FCC credit for making more spectrum available for automotive radar. “And I think the FCC did a good job,” he says. “I’m the first guy to say that they opened my eyes.”

Vision processing is another important development, he says. “The primary reason why people die in car crashes is because the car hits another car, hits a barrier, hits a bridge pier, whatever,” he explains. “Vision processing can do a huge amount to avoid that problem with a really inexpensive camera. You can go on Amazon and you can buy an ADAS [advanced driver-assistance system] device for the camera that looks forward, and will alert you for hitting a car in front. It’s available as a retrofit that clips onto your rearview mirror, and it costs $179.”

At present it might not work very well, he admits. “But next year, when the software is twice as good and the microprocessor is four times as good and so forth…”

Advancing adoption

He is frustrated by what he sees as a “very narrow” view of the field. “A lot of these technologies, radars and vision processing, and then particularly the combination of the two of them, are proving to be very powerful,” he insists.

For example, Mulligan drives a Tesla which “won’t run through a red light - it reads a red light like a human”. His point is: “So a lot of these applications that were the prime motivators of CVs 10 years ago have been superceded by other technologies.”

The FCC was persuaded that the adoption of CVs will be advanced if it chose C-V2X for two main reasons, Mulligan says: one, C-V2X is being championed by the majority of automakers; and two, non-critical messages can be offloaded to the cellular network.

He thinks the industry needs some persuasion. A lot of people, he thinks, “drank the DSRC Kool-Aid”.

“There’s thousands and thousands of engineers that have been working on DSRC, as if it’s the only game in town,” he continues. “I’m pretty outspoken about these things - but a number of the states don’t believe that anything to do with cellular is real CVs. It’s all become a faith-based thing because nobody’s got it all working. The FCC made the point that you can’t go onto a car lot in the US and buy a car with DSRC radio - nobody’s making them.”

He believes the FCC will be challenged strongly. “There’s an argument that, because the states have spent such a lot of money on DSRC, that it would be a ‘sunk cost’ if they had to remove it.”

The FCC rebuts this, he adds: “All the work that you’ve done, the design you’ve done, the consulting that you’ve done, the configuration, the network - that’s all preserved. You’re just going to change out the radio head. So it’s actually not sunk cost. But when you’re shouting so loud, it’s very hard to listen. And we’ve got a lot of people shouting at the tops of their voices and I think that blocks their ears.”

Allowing the private sector to take more of a role is important, he thinks: “We’ve turned the government into systems integrators, by selling them bits and pieces. And what we, amongst other companies, are looking to do is to help lead a change to outcomes-based contracting. Let’s deliver solutions to the government. And that will allow CVs to go ahead.”

For illustration, he compares the different attitudes of US space agency Nasa with Elon Musk’s SpaceX. “Nasa was an owner-operator of rockets, until about 10 years ago they said: ‘What we’re going to do is create a commercial space business’. SpaceX popped up out of nowhere and became a bus company - they’ve just got vertical buses instead of horizontal buses.”

Mulligan makes the point that SpaceX launches its test flights relatively quickly, and accepts a high possibility of failure: “There’s an expected 30% chance of success, and a much bigger likelihood of making a big hole in the ground.” In short, SpaceX has moved far quicker than Nasa: “It’s just right in front of us, these examples of how private sector innovation can lead.”

Delivering safety

Returning to earthbound traffic, he has sympathy for government officials who back CVs but now face replacing the DSRC equipment they’ve installed. “These are guys who’ve tried to deliver safety, to deliver the promise of CVs,” Mulligan says. “They chose the wrong radios. So what we want to do for those folks is to say: ‘Okay, what we’ll do is give you an upgrade programme – to buy back what you have and sell you what you need’.”

He likens Applied’s offer to getting money off a new iPhone 12 by trading in your old iPhone 8. Elements of the various radios can be re-used: “We can use the MAP files, use the mounting brackets, the Power over Ethernet injectors - a lot of the stuff is the same. So we’ll give you something for what you’ve got.”

Part of the FCC’s argument could be summed up as ‘use it or use it’: spectrum needs to be deployed for the common good. “We are just not going to sit on the spectrum anymore - so we have to deploy it,” Mulligan says.

Here he thinks the development of the internet could hold a clue: “The big thing the internet showed us is that we could deploy a set of technologies and deliver applications second.

“When we had mobile phones, who would have dreamed that would be our primary method of connection to the outside world? When we developed the internet, email was the killer application that really drove a lot of adoption - but YouTube came second. There was no contemplation that we’d actually deploy video or talk to each other like this. I’m looking at the TV screen with your face on it: it’s exactly like you’re here and you’re halfway across the world. This was inconceivable. So these are all the applications that follow – same as this is going to be with CVs.”

Applied’s strategy is to focus on Day One CV applications. “And the first one we chose was getting paramedics to citizens in need by turning the lights green and bringing everybody else safely to a halt,” he says.

This is powerful, he thinks, because it shows the technology actually working. “It also means we have a product that we can sell and generate profit which we reinvest in new stuff,” Mulligan continues. “There are only 6,000 RSU devices deployed in the US: that’s what we’ve got to show for the best part of a billion dollars and 20 years of effort. We’ve deployed more CV technology as a small private sector company than the whole of the Federal government. That’s possible because we focused on applications, and Day One and value - the private sector things. And following the model of the cell phone industry and the internet, it’s what you did and how it works that’s the most important, not some esoteric discussion about radios.”

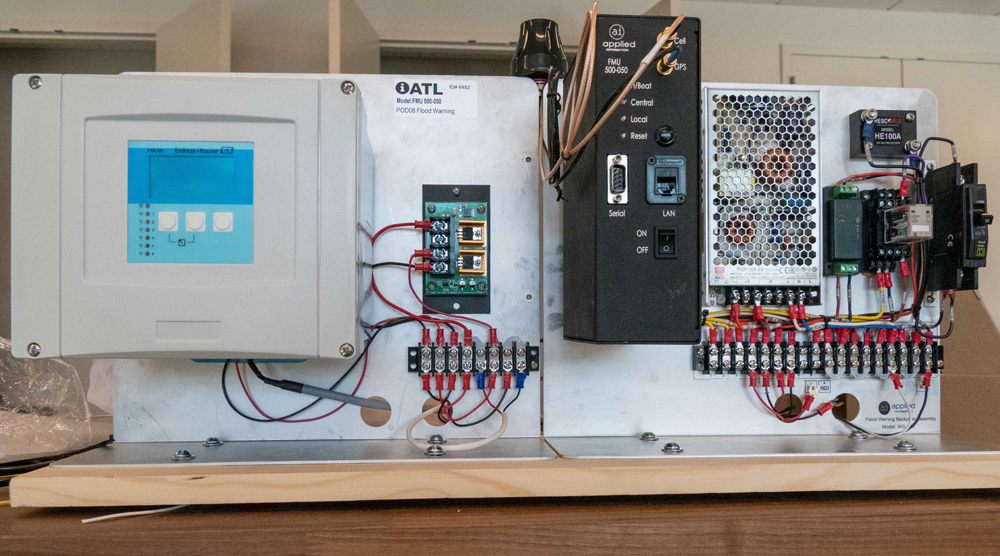

Georgia – and Metro Atlanta in particular – are seen as go-ahead places when it comes to implementing ITS technology. Applied Information’s iATL was set up with public and private money, for instance, as a facility where automakers and transportation infrastructure manufacturers can create and test CV technology and applications.

Has Applied influenced this attitude by its location, or is it a case of chicken-and-egg? “Yes and no,” begins Mulligan. “We’re an Atlanta-based technology company so we deployed our technologies in Atlanta first, because it was nearby, we had credibility and relationships and so forth. We also go to market through distribution which is a key part of this puzzle. We have been influential, but only through the success of the innovation to deliver practical solutions. Fire chiefs are a notoriously independent breed of people - you’ve got to be a special kind of person that your instinct is to run towards the burning building, not away.”

Trying to impress a fire chief by simply being a ‘good guy’ is therefore unlikely to work. But show them that your deployed technology will make fire fighters and the public safer, and that’s a message they will appreciate.

Marietta, one of the cities around Atlanta, has been running this technology and they haven’t had a crash between an emergency vehicle and a member of the public in four years. “That’s their test of CV working - they’re not interested in an argument about radios,” he says. “Their measure of success was that their fire trucks don’t hit private vehicles at traffic intersections anymore.”

And that’s the way to get authorities interested in the technology, he concludes. “Our influence comes through that mechanism of actually making it work in practice.”