Having worked in both the public and private sectors, Ken Philmus, currently senior vice president of transportation solutions at

Currently authorities have more pressing problems as the recent issues with the US Highway Fund exemplify. Despite a formula being agreed, Philmus asserts that there is still not enough money to repair, replace or upgrade America’s ageing infrastructure and he believes more authorities will consider tolling. “Already we can see that facilities backed by tolling are in a better state of repair than those that are not,” he says.

His experience is that politicians see maintaining roads and bridges as expensive and inconvenient to the travelling public (or voters) and prefer projects that will be completed while they are in office with a ribbon-cutting photo opportunity.

“Many authorities are considering tolling not only as a means of repairing and improving the infrastructure but for congestion management. In the US, in particular, we are seeing a proliferation of toll lanes, HOT lanes, managed lanes and express lanes where pricing is being used as a manager of congestion.

“Authorities in other countries do or will find themselves in exactly the same situation: more and more vehicles using older and older infrastructure.”

Says Philmus: “We know the fuel tax model no longer works. Hybrids and electric vehicles are becoming commonplace and they do as much damage to the roads as other vehicles but pay little or no fuel tax, so a mileage-based user fee is beginning to gain traction. Many states are considering this and it is attractive to politicians who are worried that simply tolling the highways will cause some drivers, and especially truckers, to divert onto the smaller local roads.

“Paying for how far you drive can be configured many ways and, ultimately, paying per mile seems to be a much fairer approach.

“This will happen at state level as we are seeing in Oregon, California and several other US States, and sooner or later we will need a major change in how we fund transportation both in the US and elsewhere. How that will fit with tolling will be interesting because, for instance, the George Washington Bridge cannot be maintained if it only receives 10 cents per mile; it would still need tolls.”

He says the sector needs to think about the long term future of transportation - decide in a sustainable model and devise how to get there - but currently that is not happening. The application of intelligent system technologies will certainly be useful and may lower the overall costs for improvement, but without a workable funding mechanism basic maintenance will prove to be very difficult, let alone changes and improvements.

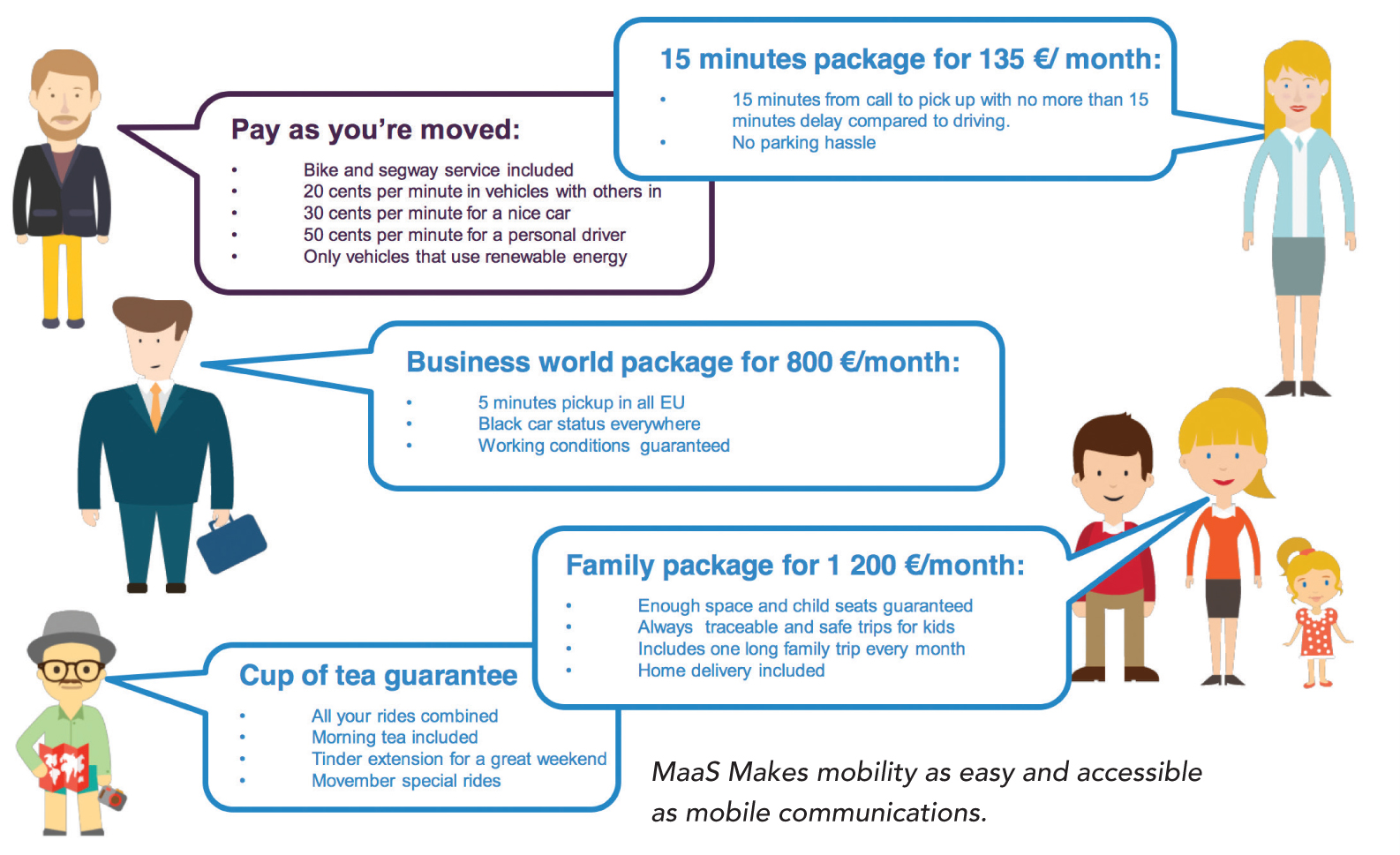

“Much of the problem is that the public and private sectors typically think in silos and focus on single modes – this will not serve anymore. What the future holds is the integration of modes and the rise of Mobility-as-a-Service [

Surveys by Xerox and others show the younger generations are not wedded to any one form of travel and do not aspire to own cars as much as in the past. Instead they are more interested in getting to their destination by the fastest, cheapest and most convenient means possible – regardless of mode or intermodal changes.

Philmus spent 34 years at the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey which manages the three major New York region airports, one of America’s largest container ports, all bridges and tunnels between New York and New Jersey, and all of the New York City bus terminals. During that time he had to consider all transport modes for both people and freight and he retains that ‘big picture’ thinking, citing the Lincoln Tunnel which he describes as a mass transit facility.

“In the morning peak more than 110,000 people pass through the Lincoln Tunnel - and 80,000 are in buses. We need to think about how many people we move not how many vehicles, and the younger generation, in particular, wants linkage to parking, cycling and walking as well as all forms of transit. That is simply not how authorities are considering things at the moment – we need to get out of our silos.”

This will be difficult as most governments around the world have created separate agencies to consider single modes which focus on their individual mandate. However, he believes that situation is changing, partly through the advent of ‘smart city’ thinking, and says this must become the norm and not the exception.

“We have to look at this holistically, not individually and government agencies worldwide are not able to adapt to all the new technology being introduced by the private sector. Globally, publically funded agencies have been repeatedly squeezed causing a huge outflow of talent to the extent that the public sector cannot keep up with what the private sector is developing. Further, publicly approved procurement systems have great difficulty keeping up with rapid technology changes.”

This will create a major lag in the implementation of new transportation technology as a major project may take five years to come to fruition while the technology can change every few months. “It will take creative and exceptional public sector leaders to take the risk to design and implement some of this technology. They should consider leaving it to the contractors and say ‘whatever is the best technology at the time, then put that in,’ otherwise the technology is five years out of date before it enters service."

His solution is twofold: public private partnerships (PPP) and pilot projects. The PPP model allows private sector participation in the project while ensuring it wants to achieve the best outcome rather than simply supplying products and moving on. In the case of technology pilots, he says politicians can minimise risk and implement projects with a degree of certainty instead of sacrificing potentially superior unproven systems for tried and tested technology.

“Politicians face re-election every two years or so - they are often not thinking long term.”

So how does he see the future? “One of the most exciting areas is the relationship between the modes,” he says citing Xerox’s management of the HOT lanes in Los Angeles. Its implementation of HOT lanes allows for a back office that can transfer benefits such as reduced tolling for those that frequently use transit as an alternative.

“It’s about managing the way people travel and encouraging them to make certain choices; looking at transport as mobility and not road, rail or transit but, ultimately, as a concept rather than in silos is the way forward. Authorities at state or federal levels or a multi-transportation unit like the Port Authority in New York/New Jersey need to focus on the mobility of people and goods rather than vehicles.” A consolidated all-mode payment system will help achieve that but agencies are entrenched, and he cites tolling interoperability, saying a technical solution has long been available but political difficulties have held the process up for many years.

"The various authorities had made substantial investments in equipment and have been unwilling to change all that equipment and investment in order to achieve broader national interoperability. We will probably get there by the end of this year but particularly for national freight movement we should have been there five or 10 years ago.”

In the longer term, he foresees that the tolling tags will be built into the number plate or the vehicle itself.

Currently, however, congestion remains a huge issue and according to Philmus, some drivers are willing to pay to avoid it – and that is not just the rich. "We've found that a teacher, a nurse or somebody with a child in a nursery is just as likely to pay to use an express lane because they have some place they need to be. And the HOT lane users typically reduce the load on the other lanes, thereby minimising congestion overall.

“Today, more than ever, we need folks that are willing to look ahead 30 or 40 years from now – it’s a real problem,” and turning his thoughts to MaaS he says: “If people are more interested in getting from A to B than they are in doing it themselves, this represents a seismic shift and a lot of current infrastructure and technology will become obsolete. This will act as a restraint on both the public and private sectors and we will not make the quantum leaps we might otherwise take unless we all adapt."

His experience is that most public agencies want to be on the Leading Edge and not the Bleeding Edge; they don’t want to be the first to try a system as it might not work - but they want to be the third or fourth once they know it works. "That’s why pilot projects with federal funding are so important - they allow authorities to effectively take a risk without jeopardising local taxpayers’ dollars. Once a system is tested and proven, other authorities can jump-in telling their voters ‘this is already working in Oregon’ or wherever."

He cites Xerox’s automatic occupancy counting system for HOT lanes: "We have had to do pilots around the world to show that it works because nobody is willing to take all the risk," he says adding, "The pilot concept definitely seems to work for governmental agencies."

One of the biggest problems he sees facing the sector is the mixing of trucks and cars on the road and points to the 14 lane, double-deck George Washington Bridge which carries more than 300,000 vehicles a day. “Post 9/11, I decided to take trucks off the lower level so the lower level was left for cars only and guess what happened? Travel times were reduced by 15 to 20 minutes for all because trucks take up so much space and people are afraid of trucks.”

Looking ahead he predicts that in another 40 years MaaS won’t be a way to travel, it will be the way to travel. "I love the idea that perhaps you pay $100 a month and get use of all the transit and city taxis and, while we will still recognise the component parts of transportation, we will see full integration and the digital world will be such that people will have less need to travel. Integration will happen in stages because it takes time for people to become comfortable with the technology. The technology, along with MaaS, will change the modal market share.

"Agencies have to change and get out of those silos. They are starting to realise that in New York and San Francisco where they are really thinking about how these services fit together and support each other. Market shares will shift and we are not need to build more highways but maybe we need more buses – whatever a bus is in those days – more rail and other technologies.”

But there will still be a need for new transport infrastructure and related technology, and funding its upkeep remains one of the most difficult problems.”