Well, that was good while it lasted. Suddenly, even in the middle of the biggest and busiest cities around the world, all was quiet. The roads were empty. The birds were singing. And the air was clear and clean.

The only trouble was that this pandemic-inspired idyll went hand-in-glove with economic collapse, and today most places are already heading back to previous levels of air pollution and environmental degradation. With, it seems, worse to come.

As lockdowns ease, millions of nervous travellers are shunning public transport and using their cars. Despite the rise in walking and cycling, plus the numbers of people working from home, increasing traffic congestion has meant that harmful nitrogen dioxide levels are rising fast right across Europe - from Paris, Rome and Milan to Madrid, Brussels and Budapest.

Outside Europe, the experience is much the same. When the lockdown ended in Wuhan, the Chinese city that was the epicentre of the Covid-19 outbreak, officials reported a 96% surge in road traffic but only a 26% increase in public transport use.

(© Ifeelstock | Dreamstime.com)

But even though the clean air bonus was short-lived, the crisis looks likely to have a lasting impact on transport strategies and politics, at both national and local levels.

According to the World Health Organisation, a 2015 survey of 51 cities worldwide revealed that traffic is the biggest source of air pollution, and is on average responsible for one quarter of particulate matter in the air of our major conurbations.

Detailed distinctions

Environmental campaigners point out that greenhouse gas emissions (GHG) and air pollutants are two distinct issues. The first is a global environmental problem but does not necessarily damage life directly in the locality. Air pollutants do.

Also, the precise impact of the lockdowns on air quality varies from place to place, depending on transport modes, industry and energy mix..

But such detailed distinctions miss the simple political and social impacts of the pandemic.

Populations around the globe have been given a short, sharp lesson in how behavioural change can deliver real and significant benefits, and voter demands for dramatic improvements in airborne pollution, environmental protection and urban quality of life have been given a huge boost by the crisis.

The challenge for transport authorities and politicians of all stripes is how to respond with practical policies that balance the needs of the economy, businesses, residents and the environment. And this is where the ITS sector is well placed to use its experience and insights to help.

Municipal elections in France at the end of June underlined the scale of the challenge. If the politicians were not listening before the pandemic, they are now.

The French green party EELV and its allies either took control or made major gains in a swathe of towns and cities right across the country – from Marseille and Bordeaux to Lyon, Strasbourg, Tours, Poitiers, Besançon, Nancy….

The ’15-minute city’

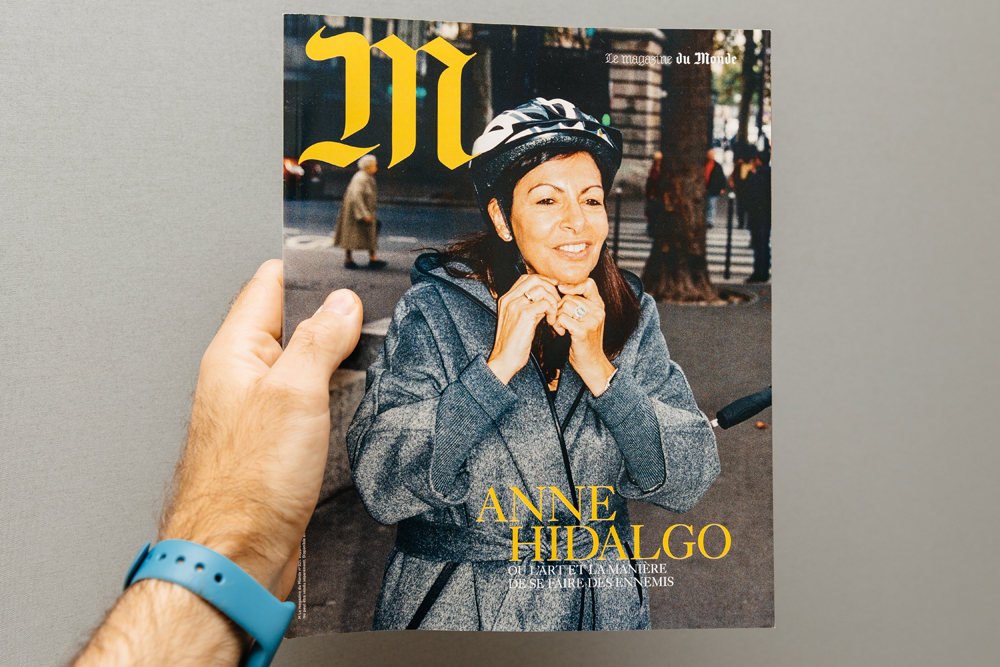

In Paris, incumbent Socialist party mayor Anne Hidalgo comfortably won a second term despite loud opposition from many car owners. Supported by the greens, she made transport and pollution central to her campaign through her “15-minute city” concept.

This radical policy envisages a city where its inhabitants can meet all of their needs – food, work, recreation, culture and so on – within a 15-minute walk or bike ride from home. It is an approach that, if delivered, will overthrow many long-standing transport and planning strategies.

Already, Paris is seeing more road space given over to bicycles and pedestrians. During the election campaign at the height of the Covid-19 crisis, Hidalgo said:

(© Christian Jakob | Dreamstime.com)

“Pollution is already in itself a health crisis and a danger — and pollution joined up with coronavirus is a particularly dangerous cocktail. So it’s out of the question to think that arriving in the heart of the city by car is any sort of solution.”

And to underline her commitment, she told her supporters in her election night victory speech: “You have chosen a Paris that can breathe.”

Andy Taylor, director of strategy for Cubic Transportation Systems, believes Hidalgo’s strategy is a positive move.

“We need to reduce commuting by bringing residences into the city and getting people living close to where they need to work – and that is going to mean a lot more mixed development,” he told ITS International. “Also, I think a lot more working from home is probably here to stay.”

Private car use will also change. “There are already increasing parking restrictions and limitations on parking,” Taylor continues. “Then there is the growth in electric vehicles [EVs] and the necessary charging infrastructure. In the US, the income previously received by the authorities from gas tax is plummeting, and a lot of cities are looking at replacing that with tolling or road charging in some form.”

Perception problem

Taylor’s immediate concern is the state of public transport systems, a crucial element in any air quality improvement plans.

“If you could end the virus and its related restrictions tomorrow, you would still be left with the perception problem – people will be so used to social distancing that travelling on public transport will be off-putting,” he warns. “Personally, I think there will have to be more central government support in some form for public transport.”

His view is that there will eventually be a switch back to public transport, partly because of congestion, but that such a return to pre-pandemic ridership will take about 18 months to two years “due to reticence, working from home and recession”.

Nonetheless, he says there is potential for a silver lining because authorities have a small window where they can rethink transport in the city.

“One major change is that people have adopted much more active modes of transport – cycling and walking,” he points out. “Even in Washington, DC, whole streets have been closed for cycling and walking and the same thing is happening in other US cities such as New York and San Francisco.”

Long view

Koen Kennis, vice mayor and the alderman responsible for mobility for the Belgian city of Antwerp – regarded by many as one of the most forward-thinking European authorities - agrees that getting people back on buses and metros is a major challenge.

But Kennis, whose city is the second-biggest port in Europe with a metropolitan area population of 1.2 million, warned against over-reacting in response to the pandemic and said authorities must take a long view (see Antwerp: investing in innovation, p30).

“When improved air quality is the result of an economy slowing down or even coming to a standstill, this is not acceptable,” he argues. “What we need are structural solutions for these problems, which means investing in innovation, research and development.”

Michael Ganser, Kapsch vice president for solution consulting in the EMENA region, stresses that pandemic response needs to deliver short-term results - and that politicians and authorities must understand the detailed implications of their actions.

“I understand the thinking behind the Paris ‘15-minute city’ concept, but it is very much a long-term approach. As a policy it is not wrong, it is just that it will take a long time to implement, and cities need quicker wins that will have an impact now.”

Most forward-thinking cities would like to see a lot more walking and cycling, he notes. “But if you are just blocking roads for traffic, then that traffic is merely pushed onto other roads, and you have simply moved the problem from point A to B. So, the solutions have to be holistic and involve - simultaneously - traffic management, congestion management and demand management as well as other measures such as active mobility and micromobility.”

Congestion charging

As with road closures, he warns that congestion charging on its own can simply make problems worse and ultimately lose public support – a critical consideration in a changing political landscape. “There has been much talk about congestion charging but most charging schemes are not delivering optimal capacity or routing solutions - they are just implemented onto the existing traffic mess,” he says.

Congestion charging should always be implemented on top of optimised road capacity and routing. “If you introduce charging, and then simply reduce road capacity through bike lanes, bus lanes and by increasing pedestrian space, you will still have a congestion problem with all the negative environmental impacts that congestion produces.”

In the short term, Ganser argues that action to deal with congestion can deliver meaningful improvements. “When you look at the damage caused by traffic – at the emissions, noise, impacts on health and so on – congestion itself is responsible for about one quarter of that impact – in peak hours even one third.

“So if you solve the congestion problem you are making a major contribution to environmental improvements and congestion is a lot easier to fight than vehicle demand as a whole.”

In the long term, Ganser agrees that “the only way forward” is to actively manage mobility demand and delivery - and he thinks that Mobility as a Service (MaaS) could be central to future strategies.

Holistic view

“The current approach of MaaS is to present the user with options and solutions, but I believe we can take it to the next level if we use the latest state-of-the-art technology to better understand the customer,” he says.

“I do not think that the whole area of incentives to influence people’s behaviour has been fully explored. For example, can we incentivise people to walk or use their bike on a sunny day instead of driving? There is clear evidence that proposing alternatives to people at the right time and occasion is a great deal more efficient than a ‘plain broadcasting’ approach.”

But whatever future strategies entail, one thing is apparent. Keeping the air clear and clean will need fully-functioning and funded public transport.

When asked what should happen next, Koen Kennis simply replied: “First of all, the impact of the coronavirus will have to be reduced by finding an antidote.”

And while a vaccine is sought, local authorities can help by taking a holistic view of transportation needs as the world emerges from lockdown.

Research: localism is key to improved air quality

Long-term policies to improve urban air quality have to be adapted to local circumstances if they are to be effective – and that will mean municipal authorities having the powers and funds to take the right decisions for their populations.

That was one of the conclusions from an award-winning research paper on micromobility and e-scooters written by French research scientist Dr Anne de Bortoli.

In her paper, de Bortoli used a model she developed while at the University of Patras in Greece to quantify the ecological impact of the emergence of shared e-scooters in Paris.

She stressed that authorities must use science-based assessments to design public policies and avoid preconceived ideas about what is ‘green’ or not. What is good for the environment in one particular country or city might be harmful elsewhere.

She told ITS International: “In my research, I was simply asking whether shared e-scooters were good for the climate – and to answer that you have to look at the issue in the round, holistically.”

From her work it was clear that the same mobility systems would not be appropriate for different countries and different cities. “For example, despite the fact that shared e-scooters have been pretty bad overall for transport in Paris, in other cities - for example in China - where the transport systems and electricity mix are different, they could be very beneficial,” she explains.

GHG increase

De Bortoli’s study found that the introduction of ‘free-floating’ shared scooters in Paris led to an increase of greenhouse gas emissions.

In Paris, urban dwellers used e-scooters mainly to replace walking, cycling and metro trips. Because electrified public transport in Paris is powered mostly by nuclear energy, its carbon footprint is already low.

Further emissions were caused by the vans used to collect and redistribute the scooters across the city and the scooters’ energy-intensive aluminium and lithium-ion batteries.

De Bortoli adds: “It is clear that the impact depends on how people change their habits. If they use shared e-scooters rather than walking, for example, the overall environmental impact could be negative. But there is no doubt that, overall, different forms of micromobility provide a huge opportunity to decrease our carbon footprint and improve the quality of life.”

Her pioneering study won de Bortoli the International Transport Forum’s 2020 Young Researcher of the Year Award. She has also added her voice to the growing number calling for a fundamental rethink of both personal behaviour and how our urban centres are planned and organised.

“Travelling less is going to mean commuting less, and in the long run urban planners will have to rethink cities, looking at the balance between jobs, housing and services within geographical areas.”