Over four days in August 2017, Hurricane Harvey caused more than 100 deaths as it delivered over 40 inches (1,000 mm) of rain to parts of Texas, leaving Biblical scenes of destruction as it went. Hundreds of thousands of homes were flooded, displacing residents and leaving a clean-up and repair bill estimated at $125 billion.

In the eye of the storm – at least in ITS terms – was Houston TranStar. The partnership of four agencies – Texas Department of Transportation (TxDoT), City of Houston, Harris County and the county’s Metropolitan Transit Authority – was the focus for anxious residents faced with massive travel disruption.

As Harvey swept through, Dinah Massie, Houston TranStar’s public information officer at the time, was responsible for answering all website emails and Facebook inquiries. “We received about 275 emails, and about that same number in

Street flooding

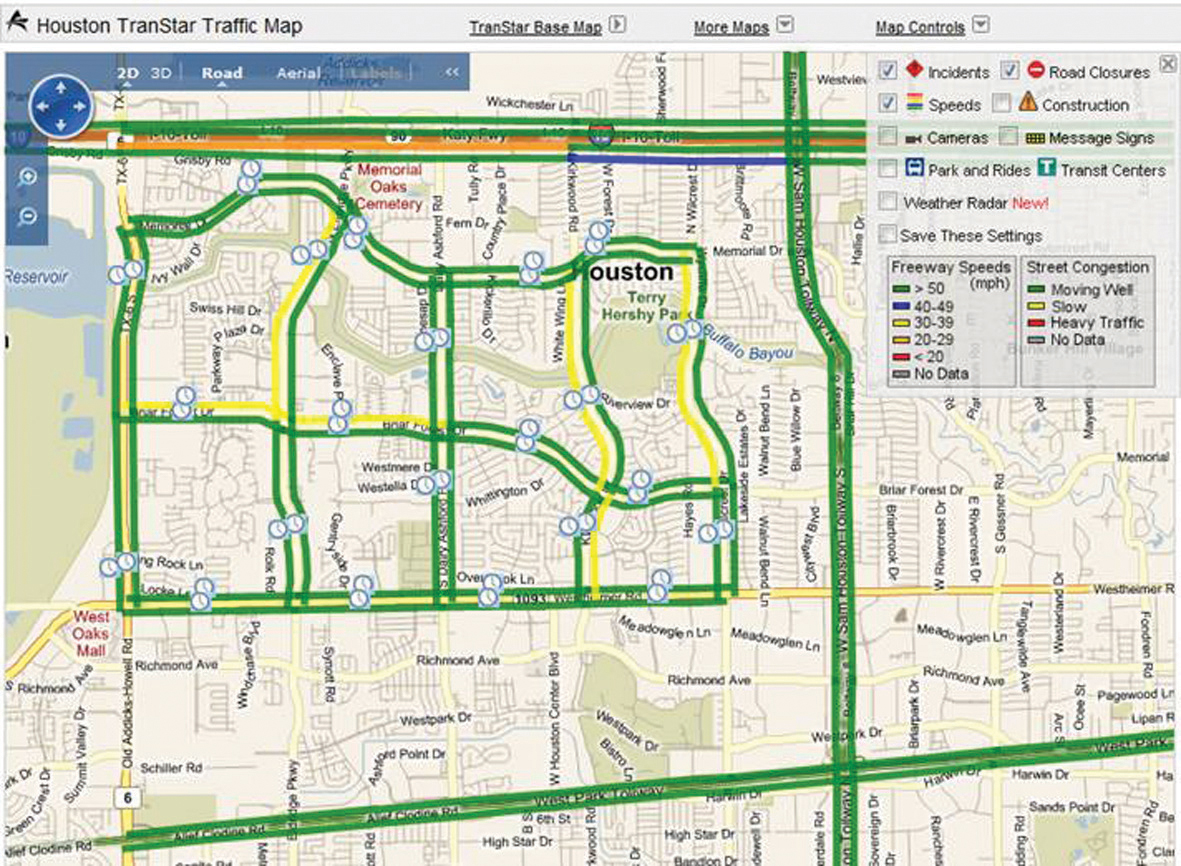

Many people were asking about travel conditions as they moved from point A to point B – which was simple enough if they wanted to stay on freeways, because the system managed by TxDoT has CCTV and 24/7 techs who enter freeway flood locations on a real-time traffic map.

However, no data existed for street flooding, and some of those smaller roads tend to carry about as many vehicles as freeways do. This led to huge confusion. Massie, who is now Houston TranStar executive director, says: “

The dangers are obvious, with motorists either tempted to try to use impassable roads, or simply unaware that they are driving into peril, thus putting themselves – and rescuers – at risk.

From this chaotic situation was born a tool – the Roadway Flood Warning System - which now predicts street flooding locations and displays the information on TranStar’s website and a mobile app. Since there were no CCTV images to access, there was no way to verify whether a local road was actually flooded. Massie found herself piecing together information from a variety of sources. “I was toggling back and forth between our map (for freeway info), Google Maps (to see if anything had been updated there) and the Harris County Flood Control District’s (HCFCD) maps to try to figure out where arterial flooding was occurring,” she says. “So yes, necessity was the mother of invention.”

Push notifications

A lightbulb had clicked on in Massie’s head. After Harvey had blown through, she contacted the webmaster at Texas A&M Transportation Institute, which manages the TranStar website through a contract with TxDOT. Her idea was to see if Mike Vickich could create a map that would incorporate better information. It turns out that he could. “By the way, he’s a genius and none of this would have happened if he weren’t so able and willing to think outside the box,” Massie says.

From her experience during Harvey, she could see that there is a wealth of data available – so long as you can pull it together and put it into a coherent package (see How does it work?) “This system will predict flooding locations based on rainfall and elevation data from the HCFCD,” Massie says. “Our next step will be to send audio push notifications to drivers when they approach an area likely to be flooding.” That is set to happen soon, she adds.

The app has been well received, and has even been recognised in awards ceremonies by Women in Transportation Services, Texas ITS and the Texas Public Works Association. Massie said media reaction was ‘very positive’ with most local TV stations – and the local public radio station, which is TranStar’s designated emergency operations communicator – covering the official unveiling of the scheme.

But what about the people who really matter, the residents who need travel information communicated clearly to them during emergencies; has it made a difference to them post-Harvey or has there been no really bad weather since to test it? “It monsoon rains here all the time!” laughs Massie. “We have had several weather events – and sometimes our so-called ‘normal’ rainfall can reach levels that trigger alarms on a localised basis.”

How does it work?

The Roadway Flood Warning System helps motorists travel more safely in the Greater Houston region by giving them information to avoid roadway flooding conditions. Harris County Flood Control District (HCFCD) shares rainfall and stream elevation data with Houston TranStar from more than 190 bayou sensors. Two thresholds must be met: First, 0.8 inches of rainfall must occur in a 15-minute window. Second, the sensor must detect the stream level in the bayou near or at the top of the bank, when the bayou is close to cresting.

“Each time these thresholds are met, the information is displayed for a 90-minute window,” TranStar’s Dinah Massie explains. “If rainfall continues unabated and the stream continues at or above bank, the sensor continues to display until 90 minutes after the rain slows and the bayou recedes.”

HCFCD sends its information to TranStar every 15 minutes. The website and apps ‘translate’ this data into a pinpoint at the HCFCD sensor location, then draw a three-mile radius around the sensor. This formula was derived after conversations with HCFCD about what would and wouldn’t work, plus plenty of testing.

“The traffic map refreshes every 15 minutes, so there is somewhat of a time lag, but we are careful to say that the area within the circle displayed on our map is ‘highly likely’ to be experiencing flooding,” Massie explains.