Colin Sowman talks to TRL’s research director Dr Alan Stevens about the future for cash-strapped road authorities’ driver information systems.

A combination of variable message signs and traffic radio in France

Colin Sowman talks to TRL’s research director Dr Alan Stevens about the future for cash-strapped road authorities’ driver information systems.

There is no doubt that the implementation of V2I systems is at that metaphorical fork in the road – one path continues the dedicated ITS route while the other embraces mobile phone and other commercially available technology. “Road authorities across the globe need to decide how to engage; and it would be far better if they all went in the same direction,” says Dr Stevens, who gave a talk on the subject in Dublin.Commercial realities mean that the technical capabilities of intelligent transport systems are far exceeding most road authorities’ capacity to deploy the infrastructure needed to implement these schemes. Dr Stevens says: “Many road authorities are currently only able to deal with the most pressing needs - be that congestion, air quality, capacity expansion or infrastructure maintenance. Other ‘nice to have’ services like an expansion of traveller information, including V2I infrastructure, are taking a back seat. The reality is that the funds to install the infrastructure necessary to expand these services are not available to many public authorities across many parts of the world.

As far back as the mid-90s

“We demonstrated that the technology could work; but it was too expensive for large scale public sector deployment and we couldn’t find a business case strong enough for private companies to invest in the system. In the end we had to remove all the beacons.

“In the past the road authorities had complete control of driver information but now they are just one of several sources of traffic and travel information available to drivers. Many vehicles are fitted with satnav and drivers listen to traffic information on independent radio stations while others may use smartphones with travel information apps,” he says.

This can give rise to conflict when, for whatever reason, the road authority wishes to use a selected route to divert drivers from a particular area. Drivers following their satnav may be sent via a different route and those using smartphones apps or listening to the radio could be directed via a third or fourth option.

Although the road authority would probably select a detour that avoids town centres and small villages, other information providers may not be in a position to be as considerate to local residents.

“The reality is that road authorities are experiencing a loss of control over driver information and need to take a step back, define what they want to do and decide how best they can achieve that aim. They need to ‘unbundle’ what they are currently doing and question whether they need to collect, process and disseminate such information themselves or whether they can efficiently and cost-effectively utilise other data sources to achieve the same result,” Dr Stevens says.

While it is incumbent on road authorities to provide safe and well maintained motorways and highways, there is normally no requirement, implied or statute, to provide traveller information or install V2I infrastructure. “Some authorities may decide to provide the roadway and limit driver information to that necessary for protecting maintenance and recovery crews. They could put up a sign saying ‘road closed’ and leave it up to individual drivers to access information about why the road is closed and possible diversions from other means, such as the radio, a smartphone or satnav.”

He feels the more likely route is that road authorities will increasingly incorporate traffic information data collected by third-party and commercial organisations. “Road authorities don’t need to collect it, they only need access to it and they may be one of several organisations to use that data. The big issue is around data quality – how fresh, reliable and robust is that information?. If the data is poor the information reaching drivers, by whichever means, will be of little use,” he says.

The use of third party data would be particularly attractive to road authorities building new or upgrading existing roads as they won’t have to invest in the purchase and maintenance of various sensors. However, if the road authority does decide to rely on third party data for new or upgraded roads, does it make sense to continue to collect their own data on the existing roads?

“The cost to local authorities of gathering that information has come down a lot. Detecting queuing traffic on motorways used to require loops every 500m and now this can now be done with CCTV, which will probably be installed for monitoring purposes anyway,” he says.

In some countries changes to legislation or the funding process may be needed to allow road authorities to purchase licensed data on an ongoing basis. Dr Stevens says: “Much of this will depend on whether the body providing driver information is state-owned or if the provision is contracted out to a separate company. Non-governmental organisations usually have more freedom in how they do business, enabling them to access data from commercial sources.”

With several sources of traffic information now available and a range of uses for that data, Dr Stevens says road authorities need to evaluate the wider benefits of driver information against the cost of its capture and presentation. To that end TRL, along with its counterparts in Austria and the Netherlands, has participated in an EU-funded project to develop COBRA - a computer model which calculates the societal benefits of various V2I systems.

COBRA computes both the costs and benefits associated with three ‘bundles’ of V2I cooperative technology; one of which requires dedicated short range radio beacons at the roadside, while the others can or do rely on the existing cellular phone and other networks. The computer model enables scenarios to be compared and calculates the benefits of each in terms of a reduction in accidents, injuries and fatalities as well as savings accrued from shorter travel times and lower emissions.

“A national road authority will be primarily concerned with preventing accidents, injuries and fatalities but there are, thankfully, relatively few of these incidents. Conversely, traffic delays are far more costly to society because although the cost to each individual is relatively low, the numbers affected are very high,” he says.

Currently the system is designed to model the motorway and major road networks in the UK and the Netherlands, but other countries’ infrastructure can be uploaded if needed.

In the tests run to date, the case for installing roadside infrastructure such as beacons alongside motorways is very weak because the costs are so high. However, Dr Stevens points out that the case may be stronger for the use of mobile beacons in specific safety situations such as temporary roadworks.

Provided driver distraction issues can be overcome, by far the most cost-effective outcome in the tests done to date is for information to be delivered via a smartphone app. This becomes even more advantageous if a third party funds the app development and subscription fees for drivers are kept low.

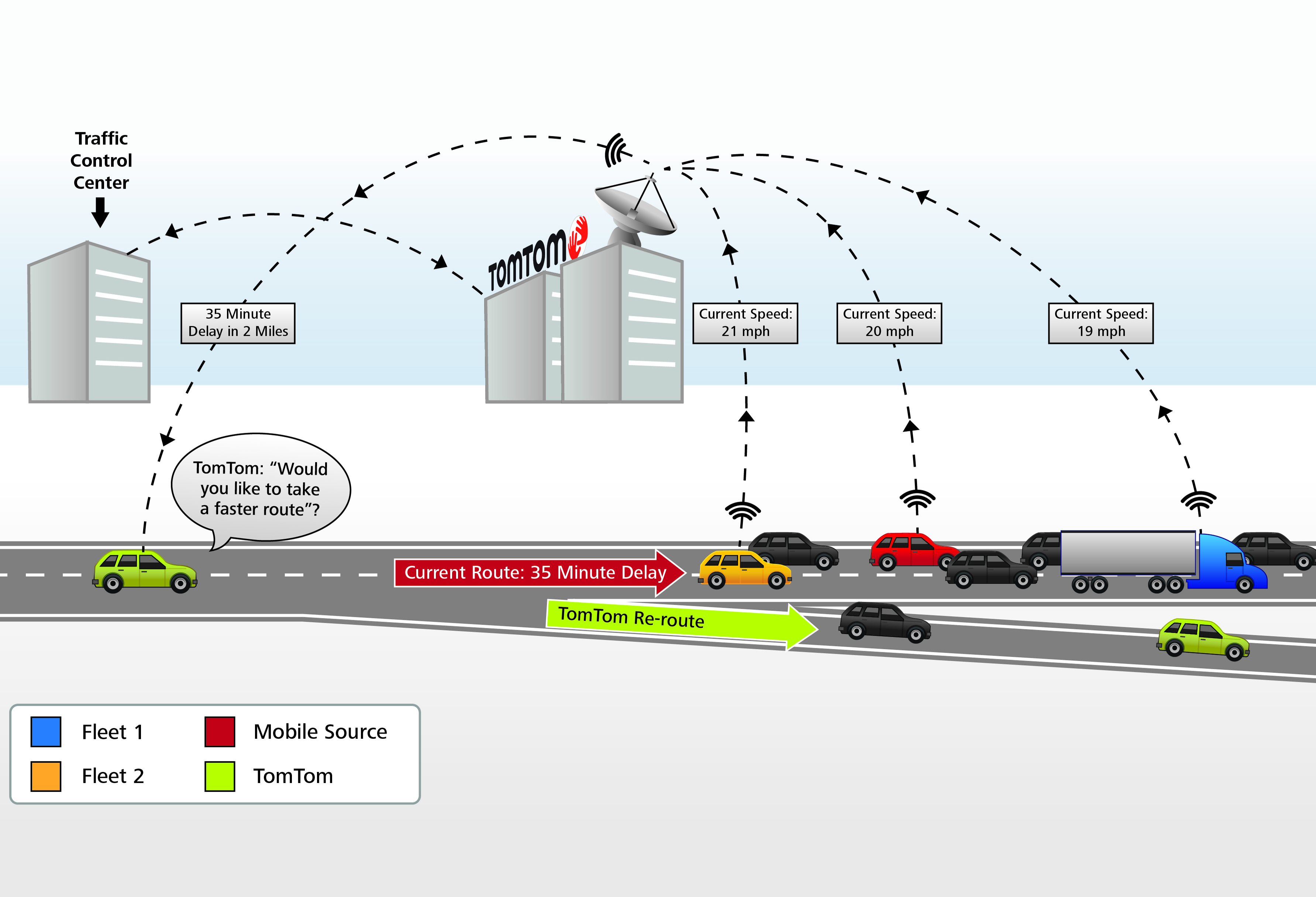

Dr Stevens encapsulates the situation by saying: “Ultimately the likes of the satnav companies have the technical means and the financial incentive to collect and disseminate driver information. What’s more, they can collect this information for all roads not just the motorways and trunk roads, so it is likely that they will become the dominant source of driver information.

“Road authorities may decide their best plan of action is to engage with the other information providers to share and potentially buy data to enhance their own service – and the EU’s Rosatte project has established a protocol to facilitate this interchange. In that way road authorities could enhance services to motorists in their area while retaining a degree of influence over the advice other service providers issue when incidents and congestion do occur.”