Road crash statistics are shocking: but there is a danger that lists of numbers become abstractions. When Lives Collide, a photography exhibition to mark the 30th anniversary of RoadPeace, the UK national charity for road crash victims, aims to show the human faces behind the numbers. There’s no escaping the grief and pain in what is at times a shattering experience. Shot by Paul Wenham-Clarke, professor of photography at the UK’s Arts University Bournemouth, the images were exhibited in London in January and there are plans to tour them in the UK and abroad.

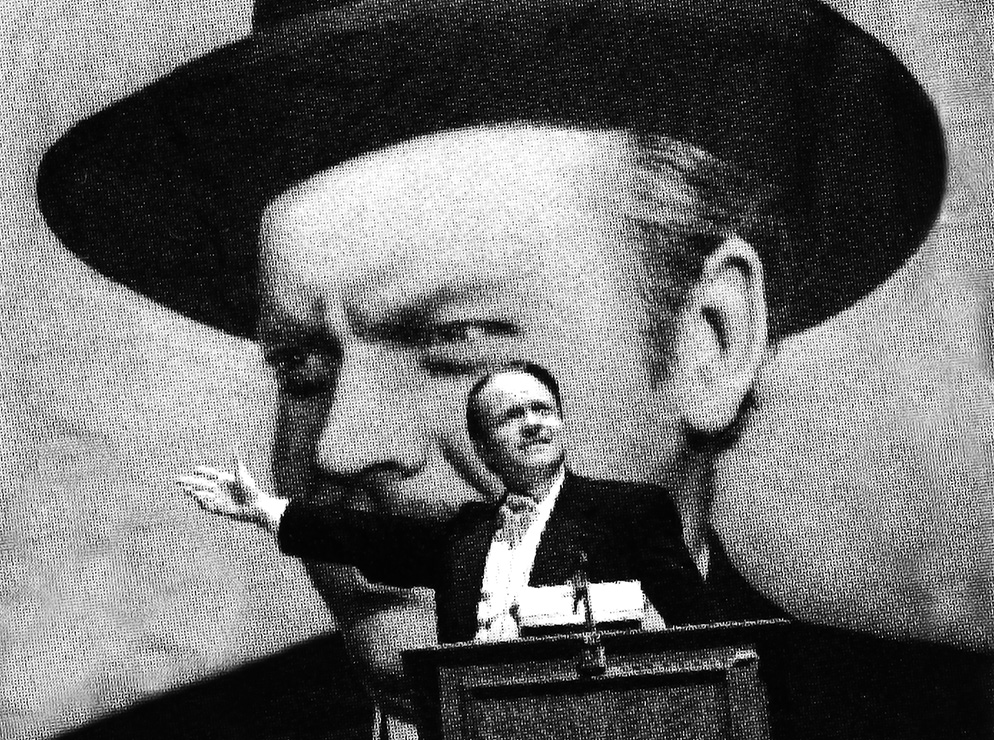

This is the second exhibition with the name – RoadPeace’s first When Lives Collide exhibition (also with pictures by Wenham-Clarke) took place two decades ago in 2002. Again, it features pictures of crash scenes as well as black and white portraits of people whose lives have been irrevocably affected by the deaths of loved ones. Designed to show that crashes affect everybody, it succeeds to an extraordinary degree. Each of the portraits comes with text explaining who people are and who they’ve lost: truly, these are the faces behind the statistics.

Wenham-Clarke started out as an advertising and commercial photographer. “When you're doing that kind of work, you get to think about how image and text work,” he tells ITS International.

He began applying the same principles to his documentary work. “I started to think: ‘how could I use the text to make the pictures more effective?’” Wenham-Clarke explains. The portraits for When Lives Collide have a write-up, with headline and detail, giving viewers as much or as little information as they want for maximum engagement.

“You can just read the headlines and move around from person to person to person,” he says. “Members of the public these days are very used to the language of advertising, so feed it to them in a way that they will take it in.”

For the original When Lives Collide, Wenham-Clarke photographed people in their own homes. The timescale for this second exhibition was too tight to allow that, so RoadPeace organised one-day meetings with its local groups and Wenham-Clarke took his cameras and lighting equipment to the various locations. “It was like a touring studio basically,” he says. “I asked some very simple questions to get things going and then they would just tell me their story - I was silent through a lot of it. When someone's telling you something painful, whatever you say sounds trite. A lot of the time it's just body language, nodding and facial expressions that let the person know you are understanding what they're going through.”

People opened up to Wenham-Clarke, and this is reflected in his powerful portraits. “With some, the emotions would literally gush out, you’d see them rollercoastering through agony moments and then choking back the tears and smiling because they remember their loved ones. It was really quite difficult to do as well: there were quite a few times when they'd get me in tears from what they were saying. And I felt if I can get some of that when you look at the picture - and then you go to the text and [the story] can be conveyed to somebody viewing that work - then I’ll be happy with that.”

The human element of the exhibition is overwhelming: in particular, When Lives Collide throws light on the trauma that’s left behind. “When you read the stories you get the sense of the massiveness of the effect on people: terrible, emotional – and also financial,” says Wenham-Clarke. “Sometimes people that are left behind, their life will fall apart because of all the financial implications of what's happening.”

His other documentary work includes a project on the Westway, the highway which splits west London, and one on wildlife killed by cars. The linking theme running through these and When Lives Collide is “the negative consequences of being so car-focused in our way of thinking”.

For him, one overriding message came through his latest work. “We want cars to be shiny and beautiful and show your status and all those kind of things,” Wenham-Clarke says. “We'd like to forget about all the pollution and global warming, people dying, animals dying - that's all ‘oh dear, it's just an accident’. And it's totally avoidable. In Britain, there's something like 1,500 people a year dying - but globally, it's a massive issue. Britain is one of the safest places to drive - so imagine how bad the bad places are. We basically get told about the statistics: so it's how many deaths a day or some figure about how many deaths are caused by certain types of driver. But what you don't get to is all the personal grief. And for every one person that dies there's a whole circle of people that are affected by it, and nobody thinks about it.”