Projected benefits from implementing Mobility as a Service (MaaS) are impressive — somewhere around $156 billion by 2022 and rising to $370bn by 2026, depending on which reports you read. Europe is currently leading the charge and the sector will be worth some £14bn ($17bn) in the UK alone by 2025, according to the UK’s Transport Systems Catapult. Yet on the ground, the rate of introducing MaaS appears painfully slow. So the question is, given the range of suitable technologies readily available, why is MaaS not more widely launched - or at least piloted in most major cities?

Speaking at ITS International’s MaaS Market conference earlier this year, Transport for London (TfL)’s head of transport innovation Michael Hurwitz, said: “The real risk with the term ‘MaaS’ is that it almost becomes the thing in itself.” His point is simple: authorities have to ensure transport is available for everybody – but, as he says, 15% of people in London do not have a mobile phone.

Yet the meteoric rise in popularity of taxi-hailing apps shows how much the smartphone-equipped majority appreciate the on-demand convenience - even though, from a city’s viewpoint, the additional movements increase congestion and vehicle miles travelled (VMT), and adversely impact air quality.

Blurring lines

A plethora of new services is also blurring the line between public and private transport. Beyond the traditional public transport and local authority--licensed taxi/private hire firms, there are now car clubs, on-demand community buses and shared taxis, bike- and scooter-share and, of course, taxi-hailing (some of which have launched with little or no interaction with the local authority). Some of these new transport options are now causing authorities problems, be that licensing concerns and increased congestion, or dockless bike and scooter ‘litter’.

For his part, Hurwitz believes authorities need to engage with new services before they are launched in their cities and cites dockless bikes as an example: “These are a new idea; there are no laws.”

Introducing services without considering the ramifications and any unintended consequences is a recipe for disaster, he adds: “A ‘launch and defend’ approach will always end badly.”

Thus his message to new mobility providers is: “If you want to come to London, come and talk to us first.”

So why has MaaS not been implemented in London? “We don’t want to do MaaS for the sake of it,” he insists, reiterating that any solution must be accessible, work for everybody and produce no additional pollution: “The solution might be called MaaS or might be deregulation.”

Regulatory anomalies

This theme is echoed by Michael Mansard, head of business transformation at subscription software specialist Zuora, who says legislative changes will be needed in many countries if multimodal travel and MaaS are to reach their full potential. He highlights the example of e-scooters: these are exploding in popularity in many cities - but cannot legally be used on the UK’s roads or pavements, which deters would-be investors. Only two have even tried to launch in London: Bird has been running a trial in the Olympic Park (which is administratively private land) while Lime has applied to TfL for permission to launch.

Most countries have similar regulatory anomalies that need rectifying.

Crissy Ditmore, director of strategy at Cubic, says all city authorities are grappling with these conundrums and the waves of new technologies and services constantly change the available possibilities and solutions. “Authorities realise that there is no point in trying to keep up with this endless stream of technology launches and updates,” she says. “So instead, many are working to define their end goals and transport policy objectives against which they can evaluate the new products and services.”

When visiting authorities, her first question is: ‘What is your end goal, your policy objectives?’ She explains: “Many reply ‘we haven’t identified those yet’ while others haven’t even started to consider the new transport solutions in that context.”

Ditmore says the difficulties this poses authorities should not be underestimated: “These are government departments. They have to get these things right and that takes time.”

Transitioning from the traditional assets-centric system (where assets owners dictate the level of service) to a consumer-centric (end-to-end on-demand mobility) model was never going to be easy. However, Jonna Pöllänen, MaaS Global’s head of early markets, believes delaying implementing MaaS-style offerings risks allowing the private sector to move in with little or no authority input.

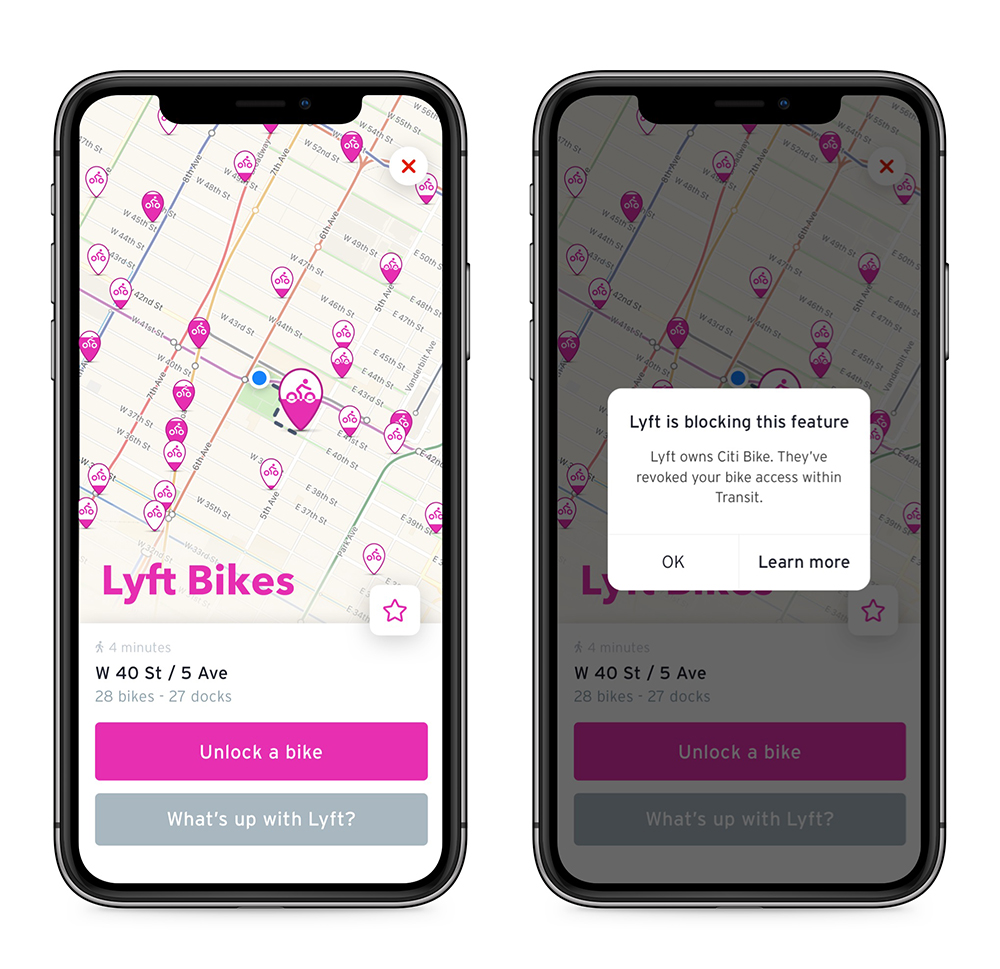

She cites Lyft’s blocking of multimodal app Transit from accessing bicycles owned by the taxi-hailing giant’s recently-acquired bike-share company Citi Bike, and the launch of Uber Bikes as examples of the private sector trying to create exclusive, standalone multimodal platforms. “The goal in creating MaaS is to make better use of the existing transport network and provide services that will benefit both the end user and the city. It is not about whether public or private is good or bad, it is about how to make those both work in good collaboration. But the type of approach being taken by Lyft will definitely not benefit either the city or the end user.”

Profit motive

Authorities also worry that commercial organisations’ profit motive sees them target the easiest and most profitable sectors at the expense of access for those with disabilities or services for less populated and hard to reach communities.

From the many authorities and transport operators she has visited, Pöllänen believes the obstacles they encounter divide into two categories: willingness and technical.

“The willingness category covers the entire transport sector,” she explains. In many cases it is the transport operators with a big market share or those exclusively operating particular services that don’t want to allow others to touch their position.” In that category, she says, are some big multinational examples, both public and private, including public transport operators, car-share, ride-share and e-scooter companies.

Pöllänen stresses that MaaS Global does not believe in a closed model approach or exclusivity with private or public transport providers and works with local authorities to agree service provision and strike non-exclusive deals with public and private transport operators. She says: “We follow an open MaaS ecosystem model where there can be more than one MaaS operator, all of which are building partnerships with existing transport providers to create the best possible solutions for end users.”

Her recommendation to cities would be to draft rules that enable MaaS to be enacted in the way they would like it to function – such as accessibility of transport services with open payment APIs. “This is one of the key factors, and the authorities have the power to demand that from providers wanting to operate in their city.”

More fundamentally, she finds that public transport in many cities is not digitised and there are still cities that have not yet implemented mobile ticketing or contactless payments, which all form the basis of mobile-based MaaS solutions. In addition, some of the private transport providers are still missing APIs used by many on-demand and multimodal services. “Those APIs could bring them additional sales channels to build partnerships with several third-party service providers.”

Open data

According to Hurwitz, the benefits from digitisation and making APIs available are considerable: “Our work on open data has led to over 80 of our data sets being made available for free, many in real-time. More than 15,400 developers have registered to use this resource and it powers around 700 apps.”

Deloitte concluded that TfL open data generates economic benefits and savings of up to £130m ($157m) per year.

A more difficult problem, Pöllänen points out, is that some cities – in the US, for example - do not yet have a public transport system capable of acting as a backbone to a MaaS-style offering. Transportation infrastructure spending is directed towards supporting the use of private vehicles rather than making it easy to cover those same journeys with clean, efficient public transportation. So, while on-demand services can get people out of their cars, if the whole journey is completed in this way there is little - if any - benefit to the city. And if those vehicles are not shared, the total VMT will increase.

Even cities with well-developed public transport suffer from this problem, leading both San Francisco and Seattle pondering levying a tax on on-demand taxi rides to counter the additional congestion and increase in VMT such services are creating.

Despite the slow pace of MaaS introduction, Ditmore is upbeat: “There are a lot of pilots going on and the authorities have learned from the private sector to try things and see where they go, iterate and try it again.”

However, with every passing month more technological solutions appear and evolve, posing a growing risk that authorities’ inaction could allow the private sector to become the dominant conduit for planning, purchasing or providing urban transport. Will Google become the way most cross-town trips are planned and paid for?

While never saying never, both Ditmore and Pöllänen highlight the complexity of administrative and fare structures, meaning the work required to implement a MaaS-style platform is considerable and bespoke to each city.

Simple and cheap

Ditmore says for MaaS-style offerings to attract end users, they must be simple to use and provide the cheapest way to complete each journey - even if the user selects a faster, more expensive option - which means the system has to apply all applicable discounts, caps and limitations. That is an enormous undertaking for each city and global technology giants can probably identify projects offering better returns for less effort.

Zuora’s Mansard also highlights complex administrative infrastructures as a major cause of delay in implementing MaaS as many cities are divided into counties or boroughs, each of which has its own transport policy.

While London is something of an exception in this respect (as its public transport is centrally planned and delivered through TfL), administratively the city is comprised of 32 boroughs which control most of the roads. Hurwitz likens London to having 32 small towns bunched together, with those on the outskirts having very different transport needs and options to those in the centre.

Other cities are also looking to centralise the planning and delivery of transport – perhaps with an eye towards implementing MaaS-style end-to-end travel. A prime example is Atlanta which has drawn together transit planning across 13 counties into the new Atlanta-Region Transit Link Authority.

In regards to fare payment and distributing revenue to transport operators, everybody agrees that this becomes much easier when users sign up to a subscription service - but the public prefers pay-as-you-go models.

This is not insurmountable, according to Hurwitz, who told ITS International: “In a sense, a version of MaaS is already available [in London] with integrated and/or contactless payments available across both public and private services. And multimodal journey planning is well established, through either TfL’s own journey planner or one of the apps powered by our open data.”

While this is not a single-app solution, it does work as around 64% of private trips in London are made by walking, cycling or public transport. However, by 2024 the target is to see that proportion increase to 80%.

Ultimately, growing urbanisation, environmental concerns and health issues mean many city authorities will be required to increase walking, cycling and the use of public transport. Whether it is called MaaS or something else, cities will need to entice citizens out of their cars and seamless intermodal travel remains the best hope of achieving that objective.