French speed camera specialist Parifex was formed in 1994 – but its work in the possibilities of vision-based systems goes back some years before that.

Even before he created Parifex, founder Pierre Peyré – father of current CEO Franck Peyré - was working in the industrial field of automation. “But at the time he was already eager to innovate, he was already trying to find new solutions and to diversify activity,” explains current Parifex sales manager Nathalie Deguen.

In 1987, Peyre senior noticed there were opportunities in vision-based systems to achieve quality control for industry - checking a product for defects at the end of the production chain, for example. Searching for partners to explore things further, he came across a specialist in industrial vision-based solutions. “And this company was contacted by a delegate from the French ministry at the time for safety and security,” Deguen goes on. “And they said they had some issues and were looking for a solution for speed control on the roads - because at the time there was no vision-based solution.”

At the time – the early 1990s – there was a fundamental issue: it was not possible to link the image of a vehicle with the speed measured. “So it was really the start of experimentation of control cameras,” she says. “Before that it was only Doppler measurements which were not connected to the picture of the infringing vehicle.”

Peyré was introduced to the government as an expert, and offered to design an innovative solution. He simply said: “Yes, everything is possible.”

“They explained what was the issue, and he tried to find a solution to offer a system to be able to link the speed to be embedded in the picture,” Deguen says.

Projects in Lyon and Angers were requested by the ministry where the system was tested - the first speed traps with cameras. In France, the first public tender for automatic speed control systems was in 2002 – Parifex did not get it. But it did win its first in 2005, for the supply and maintenance of the entire speed control system (Lynx) for the A86 Duplex for Cofiroute, installing 70 units.

“It’s a famous tunnel in Paris,” she goes on. “This was the real start of speed enforcement activity for Parifex in a structured and industrial way.”

Structured business

From this point, Peyré imposed more structure on what had previously been a business which was known for innovation and experimentation. “He really started to organise the company to be able to answer to this kind of solution and he also developed, internally, a complete solution for speed.”

Therefore Parifex as we know it today really only started in the last 15 years or so. The second tender was awarded (with Cegelec, part of Vinci Group) in 2010, again for the French government – for around 400 Vigie stationary speed traps – and in the same year Franck succeeded Pierre at the head of the company.

“What’s interesting to understand that is at the time it was a small company, facing big competitors,” Deguen continues. “And we managed to make the difference for several reasons: because of the price, because of the technology - but also because of the design.”

With a stand-out rounded, cylindrical shape to its cabinet, Parifex was providing something new compared to the more ‘boxy’ designs of its competitors. “The cabinet is really, really robust and there are two housings for air circulation, so it’s better for high temperatures. Also, for aesthetic reasons,” she laughs.

Perhaps an even bigger draw for the customer was that Parifex says this was, with its discriminating radars, also the first system in France which could achieve vehicle classification. “The innovation was that we were able to make the difference between passenger cars and trucks,” Deguen says.

Vigie cameras were able to differentiate between three categories of vehicles with specific speed limits: large trucks, coaches and light vehicles, providing accurate speed monitoring and identification of offending motorists.

Vigie cameras were able to differentiate between three categories of vehicles with specific speed limits: large trucks, coaches and light vehicles, providing accurate speed monitoring and identification of offending motorists.

Peyré acknowledges that luck has been involved in the development of Parifex: this is refreshing since luck plays a big part in any successful business, but few people admit it.

“Obviously there was also a lot of work and tenacity,” Deguen points out. “But again, we were lucky that the ministry trusted a small company to provide such a big market.”

The relationship has continued, with the French government asking Parifex to modernise its solution – which led to the Vigie Double-Side Interception (DSI) technology. This enables Vigie to take pictures of both the front and rear of the vehicle in violation.

A larger access door at the rear of the conventional Vigie allows the units to house the additional equipment necessary to take the second picture - the back of the speeding vehicle. The feature can incorporated into new units or added later to deployed Vigie radars. A major benefit is that it brings the identification of motorcycles into the picture.

“They needed a picture from the front and from the rear, to have more offences recorded for motorbikes,” Deguen says.

This represented the start of Parifex’s development of 3D Lidar. Before this, speed measurement itself was still made by Doppler.

“That’s why the Vigie cabinet is so big, because for all these functionalities we use different sensors,” points out Deguen. “We used one Doppler for speed measurement, another Doppler for vehicle classification, we use 2D laser for lane identification – so it was a combination of many sensors. And the idea with the Lidar is that we are now able to do all these functionalities with only one sensor.”

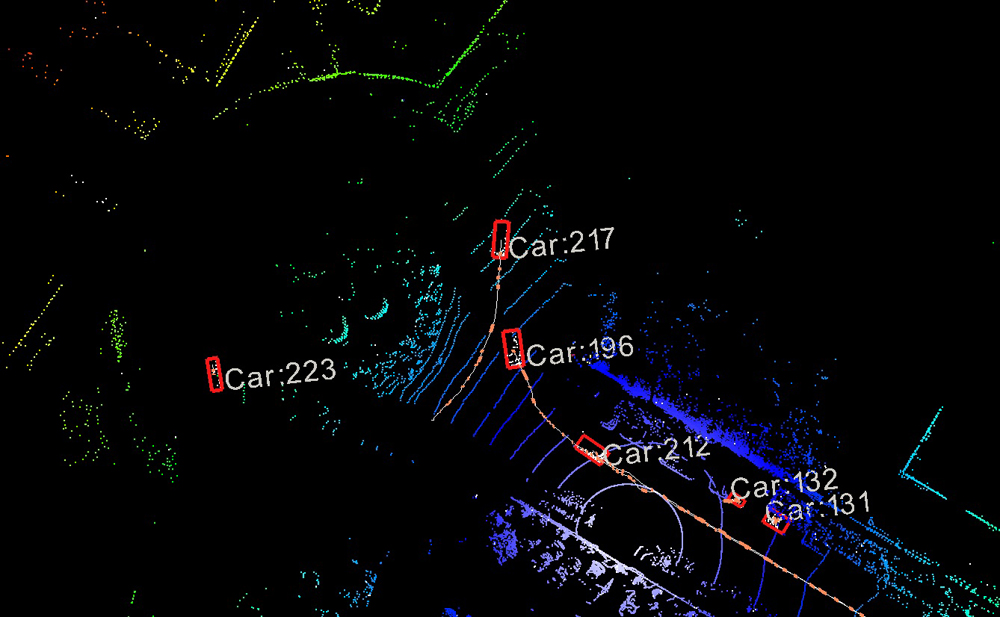

It took some time to adapt for legal reasons, certifying the 3D Lidar for speed. “We needed a solution to tracking the vehicle. The 3D Lidar actually makes the trigger for the pictures: so when the vehicle approaches it detects and tracks it, and we make sure that the second picture is of the offending vehicle. And if the vehicle changes lane we’re still able to track it.”

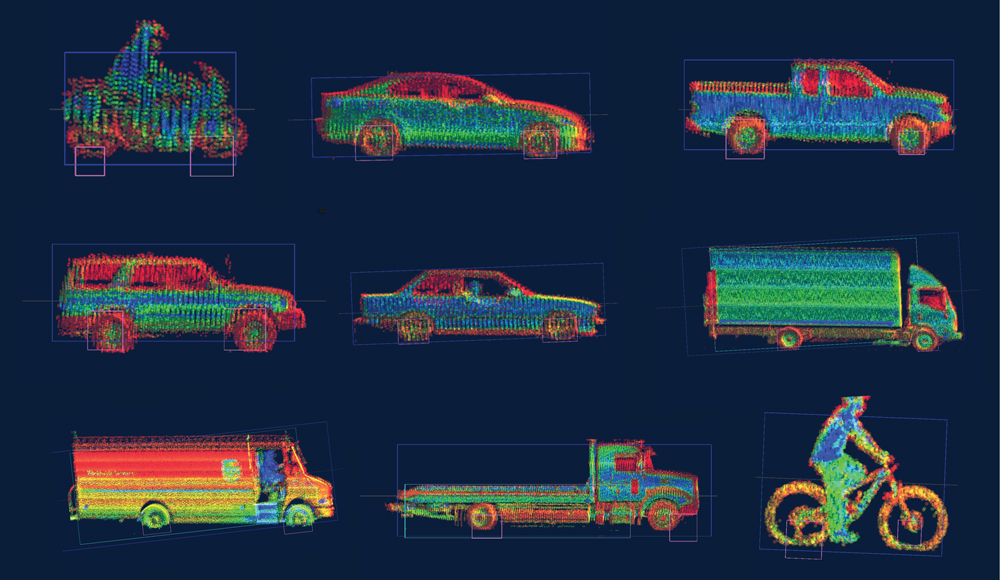

Parifex found that this was the only technology to give such a rapid response. “It’s almost like a video: we have the precise information in real time that allows us to track the vehicle. We developed our own algorithm to analyse this data. With the software we detect any moving object in the field of view of the Lidar. And for each object, we retrieve information such as the precise position, the speed, the direction, the acceleration rate, the dimensions - and from all this we can classify whether it’s a car, truck, motorbike, pedestrian and so on.”

AV navigation

So to start with, 3D Lidar was a means of improving the performance of Parifex’s existing system by offering tracking functionality, along with vehicle identification and classification. But things have moved on. Transdev contacted the company to see whether it could help with its own autonomous vehicle (AV) project in the northern French region of Normandy.

“They were trying to find a solution to AV navigation,” explains Deguen. “They wanted to equip roundabouts to increase the field of view of the vehicles.” Sensors were installed in the infrastructure on roundabouts, with Parifex’s 3D Lidar detecting all moving objects.

“There are lots of blind spots, often there are walkabouts, and we communicate this information to the autonomous shuttle so it knows what’s happening on the other side of the roundabout. With our solution, we’re able to let them know: ‘Be careful, there’s a car approaching, there’s a pedestrian crossing’.”

It was a ‘lightbulb moment’ for Parifex. “That’s when we noticed that there could be some other application from speed enforcement,” Deguen says.

It was a ‘lightbulb moment’ for Parifex. “That’s when we noticed that there could be some other application from speed enforcement,” Deguen says.

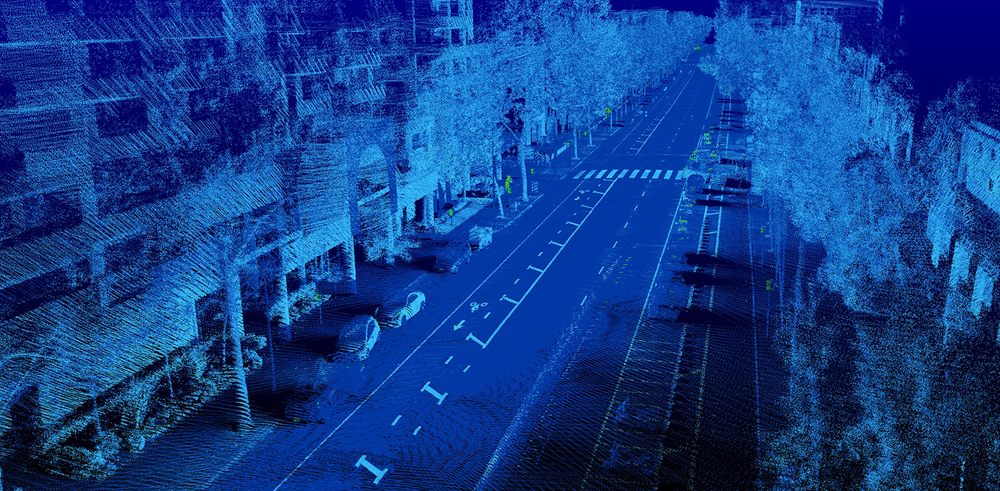

From measuring speed reliably to helping AVs was one jump – but Parifex saw the potential to make another with a further use of 3D Lidar: smart cities. “It could be used as a sensor for data collection, installed on existing infrastructure or on a tripod – like Vigie Mobile.”

The Parifex sales team grew to take advantage. “We noticed there were a lot of opportunities,” Deguen says. “Basically the start of our discussion was always to show what the system could do: ‘These are the advantages of the Lidar, this is what we can see, this is the kind of information we can collect, this is how the system could help you – do you need it for any specific reason?’”

Parifex found that clients themselves had ideas about what they could use it for: issues with parking, for instance, or to get more granular information on traffic management. The company invested more to try to offer solutions for these varied applications, creating a new division dedicated purely to smart cities. So far there have been no smart city deployments, but Parifex feels it could be at the beginning of something big.

While enforcement has been what the company is best known for over the last decade or so, more diversification is clearly on the cards. But Deguen insists that the core will remain: “We need enforcement. This is our business, historically; we have some great references, we are well known as experts in this field and I think this will help us to diversify: it’s in its very early days but these activities are closely linked.”

In 2021 Parifex will deploy its new multi-violation urban radar system, Nomad, as part of the roll-out of a new contract.

“We know that the ministry and some cities are always thinking of adding new functionalities - traffic counting, for instance. The idea would be for one system to be sufficient, not only for enforcement but for recording statistics to monitor drivers, checking that the driver is not using a phone, that they wear their seatbelts, et cetera: these are all really important things for safety, and for changing drivers’ behaviour.”

International expansion

The deployment in 2021 will involve 2,000 housings and 500 units – far more housings than cameras, in other words. This is a standard approach by road authorities everywhere: moving the units from place to place not only means drivers must assume they are being surveilled all the time, but it is less expensive than populating every single housing with a camera.

In France the company has a strong foothold but has offices in Poland, and part of the production of its cabinets takes place in Malaysia.

“Developing internationally is pretty tough,” Deguen concedes. “So we’re trying to build partnerships with bigger companies, such as Cegelec. The idea is to be able to offer clients a complete package of the solution.”

Starting in foreign countries will naturally require a different approach. For speed enforcement operations to be effective, you don’t just need cameras on the road containing clever technology – you require data centres, offence processing software and back office operations, communication and so on.

Parifex does not offer this full service on its own. “We can only provide the system itself,” Deguen says. “So we are approaching countries in consortium with partners like Cegelec to offer a complete installation.”

Parifex believes that breaking into new markets requires partners – other companies with whom to share the load. “I think it’s a better way to answer the clients’ needs,” says Deguen. “You need to be able to manage the project and understand exactly the difficulties that the clients may have, and to bring an expertise to the client with some companies that know how to install these kind of solutions.”

Parifex believes that breaking into new markets requires partners – other companies with whom to share the load. “I think it’s a better way to answer the clients’ needs,” says Deguen. “You need to be able to manage the project and understand exactly the difficulties that the clients may have, and to bring an expertise to the client with some companies that know how to install these kind of solutions.”

It is still a tough area to crack. Speed enforcement contracts tend to be made by public tenders – and this creates other issues for providers. “It means it doesn’t happen every year,” explains Deguen. “In some countries you might be missing some financing, they need the budget, and perhaps they have a new minister so they have to start everything again.”

Artificial intelligence

Some tenders are launched and then promptly cancelled, leaving manufacturers kicking their heels while they wait for another opportunity – which may be two years down the line. This means that flexibility is crucial.

“So basically your idea is to be able to react rapidly and efficiently if there is a tender,” she says. “We are waiting for opportunities so for us it’s just a question of trying to be known so we are consulted by the end user.”

Artificial intelligence (AI) and image processing are other areas which Parifex is zeroing in on – linked to its new contract for the Nomad multi-violation system. “One of the advantages is that it’s completely non-intrusive, meaning it doesn’t have to be connected to streetlights, we use the camera to detect the status of the lights,” Deguen explains. “So that was the start of the development of image processing solution. We also had to develop our own ANPR software and we use our image processing to do that, combined with the Lidar detection, and for other functionalities such as detecting drivers’ phones and seatbelts.”

Deguen is at pains to highlight the importance that Parifex attaches to developing new products. “We invest 15% of our turnover in R&D,” she continues. More than this, during the Covid-19 lockdown, when many companies in the transport and mobility industries have understandably struggled, Parifex has even hired 10 more people to bolster competencies in AI and image processing in the R&D team with a view to working on the new projects the firm hopes to attract. This is positive news – and there is also a hint of circularity.

“I think it’s interesting, when you think about the start of Parifex,” Deguen concludes. “Our expertise was more into vision-based solutions. And then we developed a new solution for speed measurements using Doppler, then Lidar – and now we’re also back to image processing and being able to combine all these technologies to offer the best solution.”

The innovative spirit of Parifex founder Pierre Peyré is still very much part of the modern company, it seems.