Light detection and ranging (Lidar) technology has been around for more than a decade and its 3D distance-measurement capabilities are seen as a key element in the future success of autonomous vehicles (AVs). But Dr Jun Pei, the boss of Silicon Valley start-up Cepton Technologies, thinks Lidar can be used right now for something even more fundamental. When Pei, an engineer by training, worked at Lidar inventor Velodyne more than 10 years ago, Lidar was “a fashion product, a new thing for the Darpa Grand Challenge [an AV competition funded by the US Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency]”, he recalls. “And over the last, say, five years or so it has become more and more of a norm as almost an enabler for AVs.”

But Cepton “only partially” sees Lidar in this way: it is more interested in the technology’s role in advanced driver-assistance (ADAS) programmes. “As Lidar technology becomes more and more mature and the cost becomes lower and lower, we actually consider Lidar as a safety device for cars,” Pei explains. “It’s almost like your temperature sensor in your radiator.”

Such sensors did not use to exist in cars. Pei often drives from his home in San Francisco to Los Angeles, a six-hour journey. Thirty years or so ago, at the side of the road, he would always see “one or two cars broken down, you know, with some smoke coming out”.

Warning sensors

But not anymore, he says. And the reason for this is warning sensors telling you to get to a garage before teething problems with the engine become a full-blown crisis. “Of course that’s at a very low level: ‘don’t

break down’,” he points out. “But the next level of sensor is ‘don’t get into an accident’. As it becomes mature and the cost becomes reasonably low, Lidar will actually become a critical safety sensor that can cover many, many things that the radar and the camera cannot cover.”

Combining radar and cameras means you “take care of 99%” of the safety issues that a driver will experience on the road, he says. “The problem is that 1%: you cannot just claim that every time you drive a car, one out of 100 times you’re going to die. That’s not very good.”

The 1% in this case is “the most difficult part - all the corner cases when the person shows up from the side of the road, in the darkness”.

“All of those are the critical problems,” he goes on. “People are spending billions of dollars on software and hardware and Lidar actually gives you a solid angle to detect that 1% of trouble and gives you the extra margin of safety. So it’s a small fraction, but it’s very, very valuable.”

Pei explains why Lidar can handle this 1% when camera and radar together cannot.

“With cameras, everything is about lighting. When anybody presented to me in the past a new camera technology I always ask one question: Does it work when there is no street light, in the dark? The answer is always ‘no’.”

But driving at night is not a scenario we can avoid - and Lidar does not have a problem with light. “It’s an illuminating device; it shoots in the range of the field of interest, then receives the light coming from the obstacles and detects and measures the distance and location, and gives you the XY coordinate of those points so that the software can actually take a measurement,” Pei says.

Cameras or radar in effect mimic senses, and so rely on what they see or hear. As such, both are prone to errors; a camera may miss something due to a bad reflection or fog. Radar, meanwhile, listens for radio waves rebounding. Because of this ‘rebound’ effect, it can also be likened to the sense of touch, but it lacks accuracy, only able to identify physical barriers in its way.

Lidar is different. “We’re touching,” Pei says. “We actually extend our hand outside and feel what is out there. You touch something and it gives you a feedback – ‘oh, there’s this thing’. So one is ‘look’, the other is ‘touch’. So Lidar gives you that extra level of reliability, that’s the big differentiation.”

Radar has its own advantages: it can penetrate fog, for instance, and the cost is low. “The only thing with radar - seemingly a very small disadvantage but actually a big hole to be filled – is resolution,” Pei continues.

Extra level

If a car stops on the highway 200m ahead of you, it is vital to know whether it is in your lane or on the hard shoulder. “Radar can tell you there’s a car that’s stopped. But it does not have the resolution to tell you where it is,” Pei insists. “This is the limitation of radar: it has the sensitivity, has the range, it has the robustness and cost - it just does not have the resolution. So these are the fatal design issues with camera and radar that the Lidar will naturally fill in: it has the resolution, it has the robustness against either the sunlight or the darkness.”

These advantages make Lidar “the extra level of safety”: “So I am a true believer in the future: radar, camera and Lidar - these three devices - will coexist on all cars.”

Cepton is already deploying Lidar with automotive manufacturers – although Pei is tightlipped about details. It will be a few years yet but “this is not some AV demonstration from a start-up company: this is something you can buy, from a dealership, that has Cepton Lidar in it”.

He suggests that Cepton’s philosophy has always set it apart. “We actually differentiated ourselves from the get-go of the company in 2016,” he explains. “We considered ourselves to be making Lidar for the ADAS programme - not for AVs. So there are some offshoot AV programmes using us, but we really focus on our design, starting from design cost and reliability, in any engineering process.”

This element of pragmatism is crucial, he says. “You can design the most powerful product in the world – like, you know, I go back to my Stanford lab and can make a Lidar that beats everybody - except for it costs $3 million apiece and nobody would ever buy it! And then you can make the simplest Lidar that costs $1 - and nobody would buy that either because it just measures one point.”

Performance, cost and reliability are therefore the pillars of engineering methodology and Pei says: “We actually strike the right balance point, aimed for the ADAS industry.”

This was an unfashionable position in 2016, he recalls: “We were, literally, the laughing stock of the industry because we were not on the bandwagon of AVs; everybody was saying Level 4 would be there by 2018.” He pauses. “And now it’s 2020.”

ADAS bet

Anyway, the point is that the company bet on ADAS, and now that is bearing fruit. “Around the middle of last year we actually started being engaged, with real OEM programmes for Level 2 to 2.5; it is still a lot below Level 3.”

Cepton is partnering with Koito, the biggest headlamp provider in the world, making 60-70% of all the headlamps for Japanese cars. “We have the technology developed, based on ADAS, for which we own the patent,” Pei explains. “And then there’s the Japanese company’s rigour, getting into how to make the automobile part. We’re a Tier 2 and Koito’s a Tier 1, they’re big suppliers to OEMs. So there’s this entire partnership chain formulated and we’re in the midst of it.”

That begs the question of whether Lidar companies should be focused more on ADAS than AVs in order to create practical safety benefits more quickly. “Do I see AVs at Level 4 out there next year? No, I don’t. The next two years? No I don’t. Five years? No I don’t. I don’t have a lot of ‘five years’ in my career or in my life - I’m very impatient person,” he laughs. “I’m here to make a profitable business for everybody around me.”

This means ADAS will be the focus for Cepton’s Lidar business – for reasons of scale as much as anything else. “I mean, if you count how many Level 4 vehicles are out there right now – you count Waymo, you count Cruise – put it this way, a few thousand,” he begins. “How many cars were built in 2019? 90 million: if just 10% of them become Level 2 or 2.5, that’s nine million. So, we’re talking about some magnitude difference in numbers, and you cannot make any money with a few thousand vehicles. So you will stand a chance to make good money with a more tactical deployment.”

Cepton has a variety of transportation-related cases in which Lidar plays a key role. “Once the technology is getting mature, you get a few hundred dollar Lidar in your hand and you start to think: ‘What else can we do with it?’ It’s a 3D sensor so it actually does have a lot of applications.”

Software capabilities

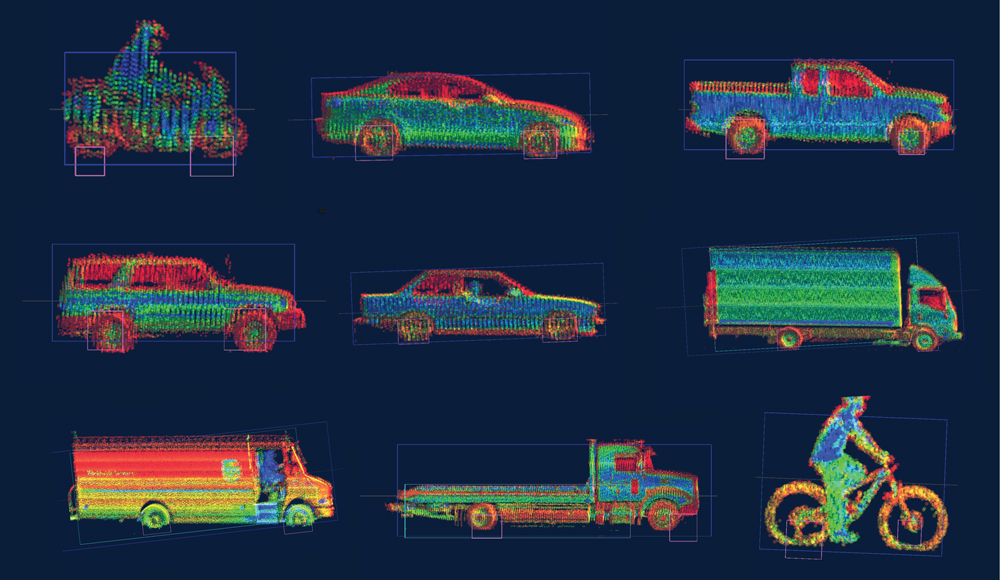

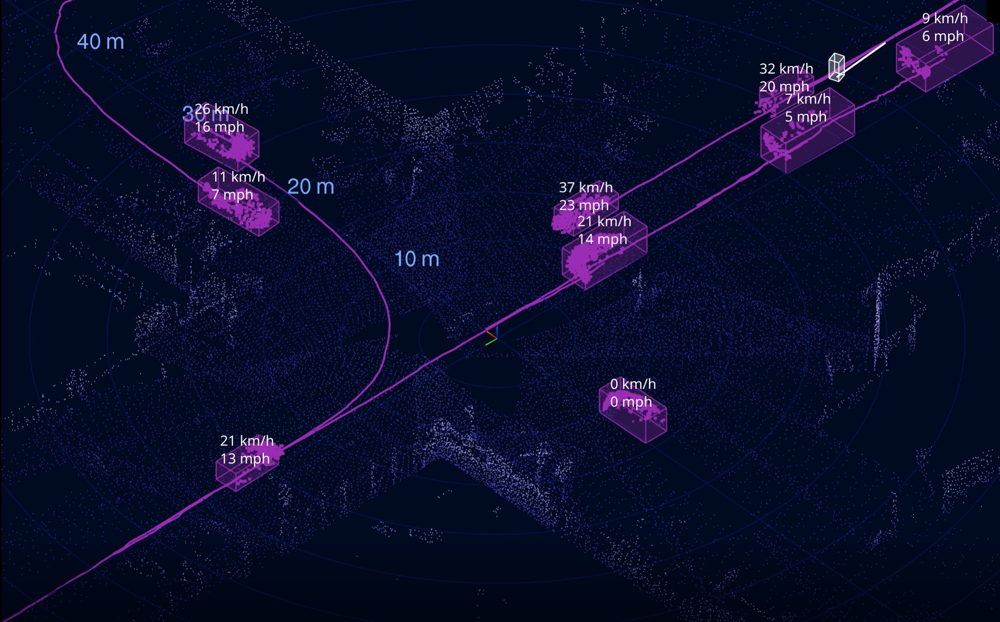

He shares a screen on a Zoom call with ITS International showing a Lidar mounted at the side of the highway to measure vehicles. “There’s the fundamental Lidar in this which captures the three-dimensional picture of the vehicle,” he says. “It can actually tell you the size of the vehicle and by applying machine learning and some level of new artificial intelligence, we can calculate how many wheels or how many axles there are and identify whether it’s a motorcycle or a bicycle. These are the capabilities of the software. So we actually have programmes with particular customers using this as a proof of concept project to do tolling. They would collect tolls associated with different vehicle types and measure vehicle violations based on size.”

These projects, usually government- or state-regulated on highways, are underway in Asia and North America. “These are the systems that would be independent of licence plate or other enforcement mechanisms: during the implementation this is a much more independent, straightforward way of doing things,” he insists. “And this is universal across the world. So, I think it will take another year or so before things start to really deploy. The tolling application is a highly reliable system. It’s also cost conscious, because there are tens of thousands of tolling stations and tolling lanes. This is just the beginning. People have realised that we could do this - and the reason is Cepton has a very unique Lidar that has a very fast scan capability. Only certain Lidar is fast enough to have an in situ measurement of the dimensions.”

This would also have a safety application, ensuring that no oversize trucks go towards a certain bridge or tunnel, for instance.

Away from roads, Lidar can be used to track the movements of crowds at railway hubs in much more detail than cameras alone, he says. “It can track all the trajectories of these people in the XYZ coordinate because it has the other dimension of measurement.” Given the coronavirus-related social distancing which is likely to be required for some time to come, this sort of data could be particularly useful.

“You can measure people’s location and monitor that each one would have a bubble around them, and whether they are violating this or keeping a safe distance,” he points out.

Some years from now the camera and Lidar will coexist - not only in cars but many other objects, he thinks. “The new iPad actually has a Lidar,” he concludes. “Of course, it’s very short distance for indoor applications - but the trend is there: Lidar in its many forms and shapes will come around and become a very useful device.”