Traffic signals have been around for a century. Garrett A. Morgan’s three-position signal was patented in 1923 and was used across North America before being superseded by the three-light version – red, yellow, green – which is still in use now. Both of these designs were based on three signals, or lights. So why are some academics suggesting that we might soon need to add a fourth - a white light or ‘white phase’ - to the three familiar colours? Put simply, because connected and autonomous vehicles (C/AVs) are coming and they will drive – or be driven – differently.

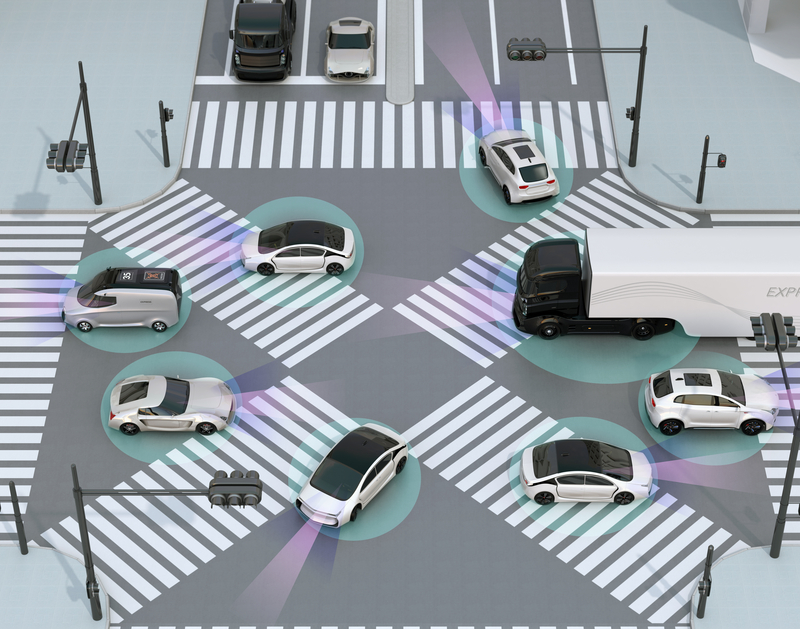

The white phase is designed to exploit the ability of AVs to communicate with other AVs and with signals; their approach to lights would activate the white phase and human drivers – i.e. the rest of us – would simply follow the AVs, knowing it is safe to do so, meaning everyone goes through an intersection more efficiently. It may also be good for other road users too.

A recent paper, Advancing the white phase mobile traffic control paradigm to consider pedestrians (Ramin Niroumand, Leila Hajibabai, Ali Hajbabaie), explores some of the issues and is exactly the sort of cutting-edge research needed if the widescale adoption of AVs becomes a reality. It is particularly important given the mixed environment AVs will inevitably work in for years – or indeed, perhaps forever.

One of the paper’s authors - Ali Hajbabaie, associate professor, Department of Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering at North Carolina State University – talked to ITS International about the implications.

“There is so much research that needs to be done when you want to touch a technology that has been out there for 100 years, like signals”

The first point is that the white light could be a – well, a red herring. “We use the ‘white phase’ term for uniformity and simplicity,” explains Hajbabaie. “We haven't done research on what the colour should be.” Flashing two traffic light colours – e.g. red and green – together could be another possibility, he suggests: “Probably something like that is a better strategy because you don't need to change signal heads.”

Anyway, for now ‘white phase’ is the shorthand to understand how the concept is going to operate. “When you don't have enough autonomous vehicles, the white phase is not going to be active: you’re going to go through green, yellow and red - that sequence,” he begins.

“There will be a time that you have enough C/AVs in a particular intersection; if you have enough C/AVs that they can control the flow of traffic at some or all of the approaches, you're going to see the white phase.”

When that happens, human drivers just need to follow the vehicle in front: “If they slow down, you slow down; if they speed up, you speed up. We have accounted for that in our models.”

Devil’s advocate

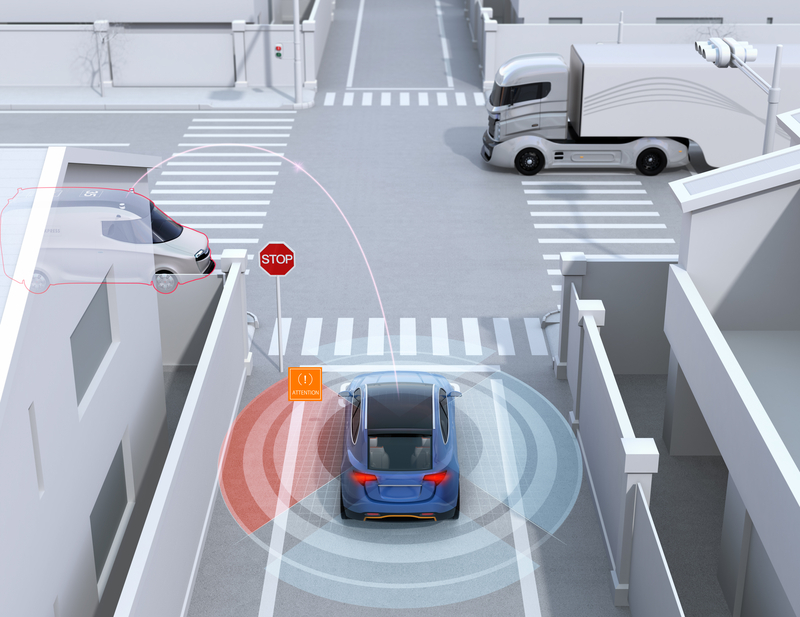

For the system to work, when following on a white phase light you would have to be going the same way as the vehicle in front; you cannot make a lane change to go in a different direction. “And you're not going to be allowed to make a lane change to, for example, pass a couple of vehicles in the intersection,” Hajbabaie adds.

The obvious devil’s advocate play here is: what happens on those intersections where you have the option of using just one lane to either turn right or to go straight on? The simple answer is that the research is ongoing. “That's a good question,” Hajbabaie says. “We haven't considered shared lanes and that's something that we are focusing on.”

Also, if an AV goes through on a white phase, just before the lights turn red, what’s to stop a red-light running human following them and causing a collision with traffic from another direction whose own lights are green?

“But that is not going to happen: the light and AVs are working together,” Hajbabaie insists. “It’s not like now, when you have two decision makers - one is a computer or a logic that controls the traffic signals, and then us drivers. The way that this whole thing works is that you have a group of AVs and you have the controller. All of these are talking to each other consistently and the decisions are coordinated. So if an AV is going through, the AV is either told by the sensors in the intersection, or by its own sensors, that two human-driven vehicles are following it. If that AV goes, it means that it has negotiated with the traffic lights, and with other AVs, and there is enough time for that group of three vehicles to go through the intersection.”

“People are sceptical and I think they have the right of being sceptical; it takes a lot to trust the technology”

There are numerous variables with all this, from communication latency, to power outage, to the sheer unpredictability of human behaviour. “With the model that we have now, we can test latency in communication, latency in response,” Hajbabaie says.

“We can test the effects of driver distraction and we can create scenarios for a loss of communication. There is so much research that needs to be done when you want to touch a technology that has been out there for 100 years, like signals. If you want to make a slight change there, you need to research how humans are going to react - a lot of different things: some of them we can do, some of them it's not our expertise. We need people from outside.”

But Hajbabaie is convinced there is significant potential for improvement in traffic efficiency, and also safety, even if not every car is an AV. What sort of proportion of AVs would you need to make it work?

“It's not just the proportion,” he explains. “Even if we [only] had 10% AVs uniformly distributed in the traffic - by that I mean that exactly every tenth car is an AV, in all legs of the intersection - you can see improvement. We could even activate white phase. But we never experience a perfectly uniform traffic distribution of AVs. So you need to get probably to 20-30% [of AVs on the road] so that you start seeing some improvements.”

The more white phase activation you see, the more improvements will be apparent “because the number of phase transitions and lost time is going to reduce”.

Levelling up

ITS International’s (slightly tongue-in-cheek) working assumption is that AVs are always “about eight years away” – two years’ ago they were eight years away and in two years’ time they will still be eight years away.

Hajbabaie laughs. “It depends on what level of automation you’re thinking about. We already have many cars that are Level 2: they have adaptive cruise control and lane change capabilities. And if you have vehicles that do that in a reliable way, this algorithm can work with them if they can talk to each other and to traffic controllers. Now, if you ask when we get to 10% with Level 5 – that’s a really tough question. I don't know if anyone has a perfect answer for that because there are a lot of moving parts. You have the technology that has to be there: it looks like that it works 99% of time, but that 1% is an issue, right? You need one bad crash to put a huge dent in the trust of the end users. But I don't think, in terms of technology, we are that far on the vehicle side.”

However, connectivity is the key to everything. “If AVs are not connected and cooperating with each other and with traffic control devices, we are not going to see huge improvements, especially now because they are programmed to be conservative, because we want to make sure they are safe.”

In lieu of an imminent mass deployment of AVs across the world’s roads, perhaps the roll-out of Vehicle to Everything (V2X) and cooperative ITS (C-ITS) technologies might help to bring white phase to more prominence. “Think about it this way: if all vehicles are human-driven, white phase is not going to work,” says Hajbabaie. “Both connectivity and automation technologies are required. A lot of times, people think that when you have white phase the travel time of C/AVs is going to be reduced more than human-driven vehicles. This is not the case: the travel time of human-driven vehicles is going to be reduced; the travel time of autonomous vehicles is reduced - and in the most recent paper that we have, pedestrians’ travel time is also reduced. So it improves traffic operation for different users of the system.”

“We already have many cars that are Level 2: they have adaptive cruise control and lane change capabilities”

White phase would work for pedestrians because the system speeds up traffic for everyone, he says: hence everyone spends less time waiting.

It all sounds splendid: but explaining all these concepts to an audience which is neither engineers nor scientists, which doesn’t necessarily understand them, and is even likely to be wary of them, is a key consideration moving forward. How can the general public be persuaded, for instance, that this technology has the potential to be far safer than what we have on the roads at the moment?

"Transparency has the most important role,” Hajbabaie agrees. “It's new technology. People are sceptical and I think they have the right of being sceptical; it takes a lot to trust the technology. It's important to make sure that we are not harming that process of building more trust by not looking at all angles of driving tests that the car has to be doing, [or] maybe pushing something a little bit too early.”

So…what colour?

To go back to where we started: ‘white phase’ is a phrase to describe something that is – at present – theoretical. It’s possible that a new indication on traffic signals – e.g. the existing green and yellow lights flashing together - could point the way to AVs and human-driven cars working harmoniously together. But then again, we may be looking at a fourth, new, white light, which would represent the first major change to road traffic signals in a century or so.

“You know, we never know,” Hajbabaie smiles. “I think from a practical perspective, it's easier to add a new indication because you don't need to change the controller, you don't need to change the signal heads. Now sometimes, research shows that a new indication is going to cause far more confusion that adding a new light, because sometimes we don't see the flashing [or] I see it flashing yellow and someone else has it flashing red or green. So research needs to be done to say which one is best. And it could be adding a new colour; if we add a new colour, I don't know what that would be.”

Research into drivers’ attitudes might show that it should be white, or perhaps another colour would make more sense. The most important thing is that people need to be made aware of the possibilities, and understand why the change is taking place.

“The key is that we need to communicate with the public - not with C/AVs - with human-driven vehicles and pedestrians that now vehicles are going to drive a little bit differently,” he concludes. “And whatever signal communicates that message in the best possible way, that should be used.”