The advantages claimed for passenger vehicles controlled by automated driving systems (ADS) remain in the future. Some may be exaggerated, others are likely unreachable due to human preferences and fears, and still others are many decades away because of built environments, human habits and resistance to change. Our progress toward removing the human driver from road vehicles will be slower than anticipated, crammed with unintended consequences, and possibly never fully complete implying there will always be some human-driven vehicles, even a century from now. This is a cultural and sociological observation, not a technological one.

The principal claim in favour of ADS deployment is safety—the potential to reduce crashes, injuries and fatalities. While I do not doubt this potential, and in fact some approaches to ADS development anecdotally appear to support this claim, experts such as Philip Koopman (Carnegie Mellon University) and Missy Cummings (George Mason University) argue that we have not yet collected enough data for a definitive understanding. It is also evident to the layman reading casual news articles that there still seems to be an unending supply of edge-cases that ADS systems need to learn.

Variable human behaviour

Beyond the concern of these experts, when we compare the safety of common carrier vehicles equipped with fully-engaged ADS (Level 4) versus that of ADS-equipped household vehicles that may be engaged arbitrarily or under select conditions by their driver (Level 3) we have far too little sufficiently-reliable evidence to gauge the safety of ADS-equipped vehicles under private ownership.

Another claim frequently heard is that ADSs can optimise traffic flow, reduce bottlenecks and enhance overall road efficiency — i.e. smoother travel and less congestion for everyone. This would surely be true in an engineered environment in which all of the vehicles involved were under standardised ADS control, but no such environment yet exists, and no-one has worked out how to convert—and afford to convert—our existing mixed-driving environments with highly variable human behaviour, motivations, emotions and attention states behind the wheel.

Furthermore, if more people are able to own and use driverless vehicles, the increase in road traffic would negate this optimisation advantage. Hence, unless we address both private vehicle ownership and how we engineer road systems, it is hard to see how ADS can idealise traffic flow on real-world roadways.

“Our progress toward removing the human driver from road vehicles will be slower than anticipated, crammed with unintended consequences, and possibly never fully complete”

Another favourite is productivity and convenience. Commute time becomes productive or less stressful when passengers can work, read or relax while their vehicle drives autonomously. Since this would hardly make any difference on short trips, it implies longer trips (which in turn implies more sprawl). Furthermore, the large majority of drivers, relieved of the task of driving, will tend to engage in social or entertainment activities as opposed to productive work or education. In other words, unless “productivity” means to engage in one’s favourite form of distraction or a nap, then this value case for automated driving is weak at best.

There have been multiple claims of environmental benefits in that ADS can optimise driving patterns - especially during stop-and-go traffic, thereby reducing emissions. While I am certain such optimisation is readily achievable and scalable, any additional road traffic due to productivity and convenience afforded by ADS would offset this. Knowing human consumption behaviours (more cars, bigger cars, heavier cars), such benefits would be readily wiped out.

Favourite-to-hate claims

One of my favourite-to-hate claims involves parking. Automated cars can drop you off, then drive away from a busy employment or shopping area and park in a cheap lot at the fringe, where they can be cleverly packed in very tightly. Or your car can drive back home, and wait there. Better yet, skip parking, and let it circle the block while you visit the dentist. Send your car off to be someone else’s problem. This is often combined with the idea of needing very much less parking in our cities.

These parking ideas imply private ownership and free road-use. Private ownership means more vehicles, more driving, more congestion, more sprawl, more road costs, and more frustration and dissatisfaction with how we commute, shop and take our children to school. It will be the same thing, just a different day — business as usual.

Among the remaining claims for the value of ADS are two critical elements of access: improved mobility for people with disabilities, and improved access to jobs, shopping, healthcare, and education for people in “transit deserts” — areas underserved by public transportation.

"Private ownership means more vehicles, more driving, more congestion, more sprawl, more road costs, and more frustration and dissatisfaction"

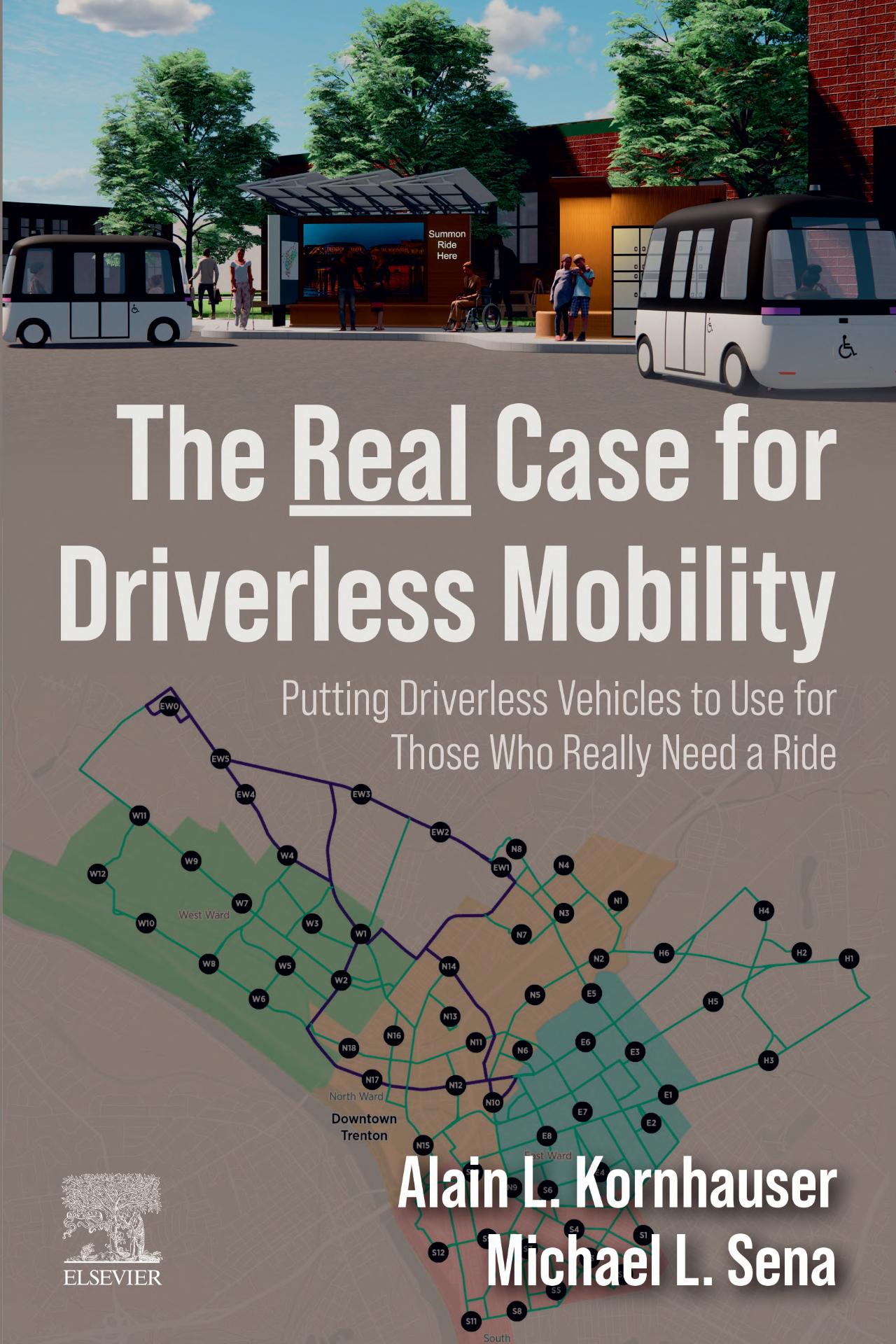

A new book by Alain L. Kornhauser and Michael L. Sena, The Real Case for Driverless Mobility (Elsevier, 2024), advocates for automated driving systems as a core component of public transportation — specifically to provide access to underserved communities. This book is sourced from Princeton University’s long-standing and highly regarded Smart Driving Cars effort, which has for years advocated the intelligent application of automated vehicles to improve equitable access for mobility disadvantaged populations.

To paraphrase from its introduction: Even where public transit is provided, a car is required for many of the regular trips persons of all ages must take. Understanding how and why cars have become the main ticket to a better life is the first step to addressing this problem. Unequal access to jobs, education, recreation and affordable, nutritious food is a direct cause of the social disorders that plague our communities.

Those who can afford to travel to where the opportunities exist can take advantage of them. Those who are poor cannot, and the cycle of poverty continues.

What better societal purpose can anyone recommend?

Another uncomfortable observation

Kornhauser and Sena go on to make another uncomfortable observation. People currently being served in the initial roll-outs of robotaxi applications in US cities like Austin, Phoenix, and San Francisco are from demographics that generally already have affordable access to personal cars, ride-hailing or transit—often all three—implying that the robotaxi companies operating there are competing with existing and plentiful supply rather than offering any societal value by addressing transit deserts.

There are several compelling reasons to adopt robotaxis as a facet of public transportation:

• Make fixed route public transit more attractive and convenient by providing first- and last-mile connectivity

• Increase accessibility for people in underserved areas or those with limited mobility; help them reach locations not covered by existing public transit routes

• Reduce congestion by using driverless shuttles to pool passengers and to replace full-size, off-peak buses when they are near-empty or infrequent

• Substitute driverless shuttles for under-utilised buses to optimise fleet management and reduce operating costs

• Driverless shuttles can provide greater service frequency at lower cost

• Robotaxis operate on-demand allowing passengers to travel at preferred times, flexibly complementing or replacing fixed-transit schedules

• Well-integrated mobility benefits the local economy; it creates mobility-related employment as well as encouraging other employers to locate or stay in a community as it can now rely on its workforce having access to its places of operation—a virtuous circle of employment and community health

• Thoughtful integration of robotaxis with public transit helps build public trust; as passengers become familiar with automated systems through shared services, acceptance and adoption grows

Subsidising robotaxis within public transportation systems also has a strong rationale. Subsidies would: make robotaxi use more affordable, encouraging adoption and reducing the environmental and parking burden of an overpopulation of household vehicles; ensure that equitable mobility services are accessible to all, regardless of income or housing location; and facilitate the transition from traditional transit to ADS-based systems, promoting a smoother shift toward sustainable mobility.

Filled with the reasons, methods and logic of addressing transportation inequity using driverless passenger vehicles, the Kornhauser-Sena book provides the reader with the history of how we got to so many mobility-starved populations, the purpose and value of solving this issue, and a roadmap to do so. I doubt you can read this, and still turn your back on the evident best purpose of deploying driverless mobility to address one of the most egregious shortcomings of so many of our cities.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Bern Grush is executive director of the Urban Robotics Foundation, a non-profit drafting an ISO standard for public-area mobile robots including a draft standard for the robotaxi pickup-dropoff problem www.urbanroboticsfoundation.org

--------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Real Case for Driverless Mobility is written by real experts from first-hand experiences, including the mobility requirements for people with special needs.

Dr. Alain Kornhauser is professor, operations research & financial engineering, and chair, Princeton Autonomous Vehicle Engineering, Princeton University. For decades, he has been singular in his focus on autonomous taxi and urban transit to enable widespread, equitable mobility.

Michael Sena has worked in the automotive industry for over 40 years with advanced driver assistance systems and services, covering all aspects of their design, development, sale, use and financing.