Xerox’s David Cummins talks to Colin Sowman about the lessons for city authorities from its survey of younger peoples’ attitude to transport.

There can be no better way to get a handle on the future of transport demand than to ask the younger generation about how they view and consume today’s transport. Sociologists have called this group Generation Z – those born between 1995 and 2007 – which will make up 40% of all US consumers by 2020. This group of consumers are behind today’s technology-driven culture and transportation agencies are keen to know if Gen Z will build on the Millennials’ sharing economy or have different expectations about how to get around.

David Cummins,

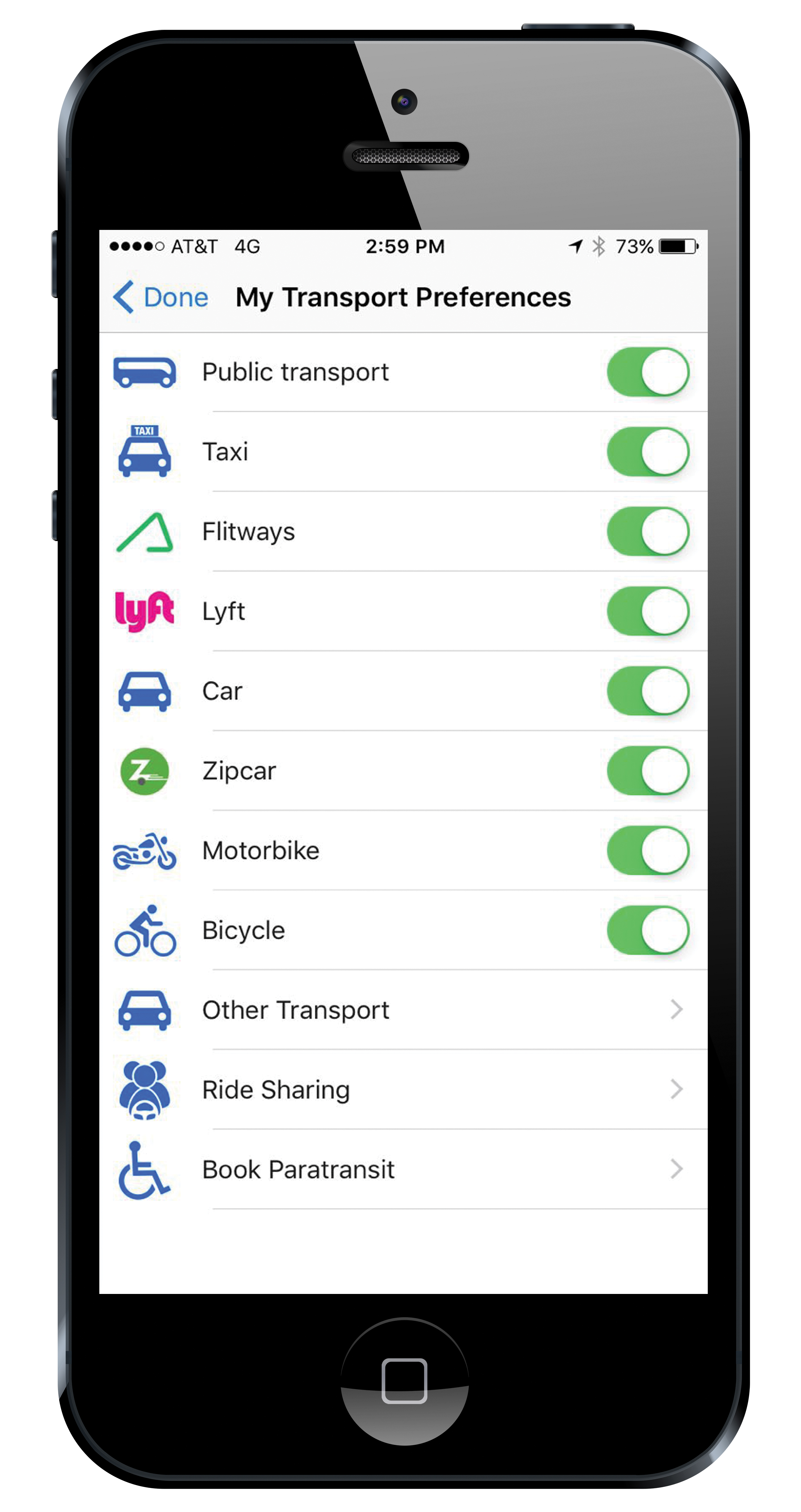

The younger generation also has extra options. “They are very comfortable with technology, the sharing economy and mobile payments so calling a Lyft or Uber car is second nature to them and can be far cheaper option than owning their own car. Owning a car is no longer the right of passage it was for older generations,” says Cummins.

Increasing urbanisation is another factor in delaying car ownership because public transport is more accessible in towns and cities than in rural areas. “Authorities see the pool of talented young workers as a source of economic development and if they can make it easy for young people to live in and move around the city, then that is a source of economic vitality for them. So city authorities are looking at how to leverage innovations in the private sector, the Lyfts, the bikeshare, Car2Go and so on, for the residents and commuters and the younger generations are already the biggest users of these services.”

According to Cummins, the upshot is that cities are starting to realise that they do not have to build everything – in fact they can’t build everything – and are embracing what the private sector has to offer. A move away from fixed assets to on-demand, from ‘I will go to the fixed asset’ to ‘we will get transportation to where the demand is coming from’.

As a result he predicts US cities will increasingly adopt a European-style approach of restricting the use of cars – especially single occupancy cars – in city centres and aim to make the downtown areas more walkable.

In regard to parking he sees a trend towards reducing the provision of parking spaces in residential areas: “Usually this is around high-rise apartment structures. They used to have a requirement for one or two spaces for each unit but now they are really lowering those requirements. In fact, they are going in the opposite direction; offering developers incentives to locate near transit stations or to include a bike share facility to persuade the apartment dwellers not to own a car.”

Frustration with the time and money wasted in commuting is also causing people to move from the outer suburbs back towards the cities.

As Gen Z move away from their parents’ suburban homes and start families, they will evaluate the housing and transport costs of living in the suburbs and assess the time wasted in commuting. Cummins believes many will decide to live nearer their workplace – often in the cities - and will commute and get around by walking, using a bicycle or public transport. The money they save can be used to help finance bigger/better accommodation in the downtown area.

“People in general, and younger people in particular, perceive living in and moving around in cities as far more attractive than it used to be,” says Cummins.

He sees autonomous vehicles being deployed in city centres far sooner than many imagine - although these will be vehicles owned by corporations and administrations rather than private cars. He envisages shuttles capable of carrying about 15 people and running from the suburbs in dedicated lanes on the arterial routes. These will be complemented by three-wheeled pods carrying two or three people that will run on the side-streets with the combination making “a very nice complement to public transit.”

Again, it is likely to be the younger generations that first utilise such solutions: “They will be the first adopters, the most rigorous users and it will be the primary way they travel around urban areas. They are very comfortable with much of the technology and for them privacy is not as big an issue as it is with older generations.”

He sees concerns among city authorities that the more affluent, and older, generations will use self-driving cars to visit a restaurant and their cars will circle around the city until summoned for the drive home. “That will just cause more congestion so I’m convinced that self-driving cars will be heavily regulated – perhaps over time rather than initially - and with the concern surrounding insurance and liability, my guess is that they will be predominantly owned by corporations.”

That, he explains, does not mean that local authorities can withdraw from providing transport and leave everything to the ‘Googles, Teslas and Ubers’. “There are still equity issues and you can’t replace metro systems with self-driving vehicles, although there may be less emphasis on fixed route buses and more investment in extending commuter rail and metro networks. Then the fixed route buses could conceivably be reduced and supplemented with autonomous vehicles for the first/last mile of journeys.”

He highlights places such as Hong Kong – densely populated cities that function very well using mass transit – saying: “There really isn’t much need for autonomous vehicles in downtown Hong Kong. They have figured out pretty well how to do things using just mass transit, so AVs wouldn’t add much to the mix – but they would in surrounding parts of the city and the arterials leading into the city. That Hong Kong-style mass transit model will be with us for a very long time.”

However, where cities do want or need AVs he feels this may require dedicated lanes until such time as the public have full confidence in the technology. This would mean the reallocation of roadspace which would reduce capacity for normal vehicles.

“One thing is for sure; whatever happens the drivers of single-occupant vehicles will be pushed to other forms of transport.

Cities may want to impose charges for drivers ‘per passenger mile travelled’ as a way of encouraging high-occupancy vehicles while discouraging the number of trips downtown made by the AV-owning corporations. So the infrastructure and regulatory structure will have to change to make this all work because the transition could be awful with competing AV-owning corporations trying to ‘claim’ a city by sending in lots of autonomous shuttles and cars. This will cause a spike in congestion until individuals migrate to AVs, shared use or other modes as opposed to driving their own car. The potential for a congestion spike has to be dealt with up-front by the city authorities to prevent this occurring.”

Currently, he does not see any signs of authorities taking this type of action but says it is understandable given the uncertainty of how AVs will develop in terms of timescale and capability. “So I can see why authorities are concentrating on the problems they have today.”

An indication of the increased interest in mobility systems of the future is that 77 cities applied for the USDoT’s Smart City Challenge grant. “Each city had to put together an application and there was an amazing amount of creativity around autonomous vehicles and other new forms of mobility. These cities want to be at the forefront of this ‘revolution’. So while there is a lot of fear and uncertainty, there is also enthusiasm and determination to say ‘we can do this, we can tackle congestion’, and that’s encouraging.

“As most cities have long-established real estate and infrastructure they cannot afford to tear down, there will not be a ‘one-size fits all’ solution for future transport and the more progressive cities are aggressively piloting new technologies and models. While there are risks to these pilots, they are usually at no-cost to the local administration so I think we will see lots more as each authority tries to figure out what could work for their city.”

That, after all, is what they are employed and elected to do.