Colin Sowman catches up on some of the latest research around outdoor pollution and looks at options available to authorities in areas of poor air quality.

Iair quality hasn’t already reached the top of the agenda in transportation department meetings in your area, it probably soon will with national, trans-national and even global bodies calling for authorities to reduce pollution levels.

The driving force behind this global focus on air quality is encapsulated in the

So although the costs of implementing changes to road transport may be high, the OECD suggests the benefits of reducing air pollution could easily outweigh those costs.

Poor air quality aggravates health problems such as asthma and heart disease and tighter emission controls on new vehicles has seen air-quality related premature deaths fall by 4% in the OECD countries between 2005 and 2010. In contrast, the increasing prosperity in China, India and other emerging economies has led to increasing motor vehicle ownership that has outpaced emissions reduction and China recorded a 5% increase in air-quality related premature deaths while India saw a 12% rise. Globally the result was a 4% rise in premature deaths over the period.

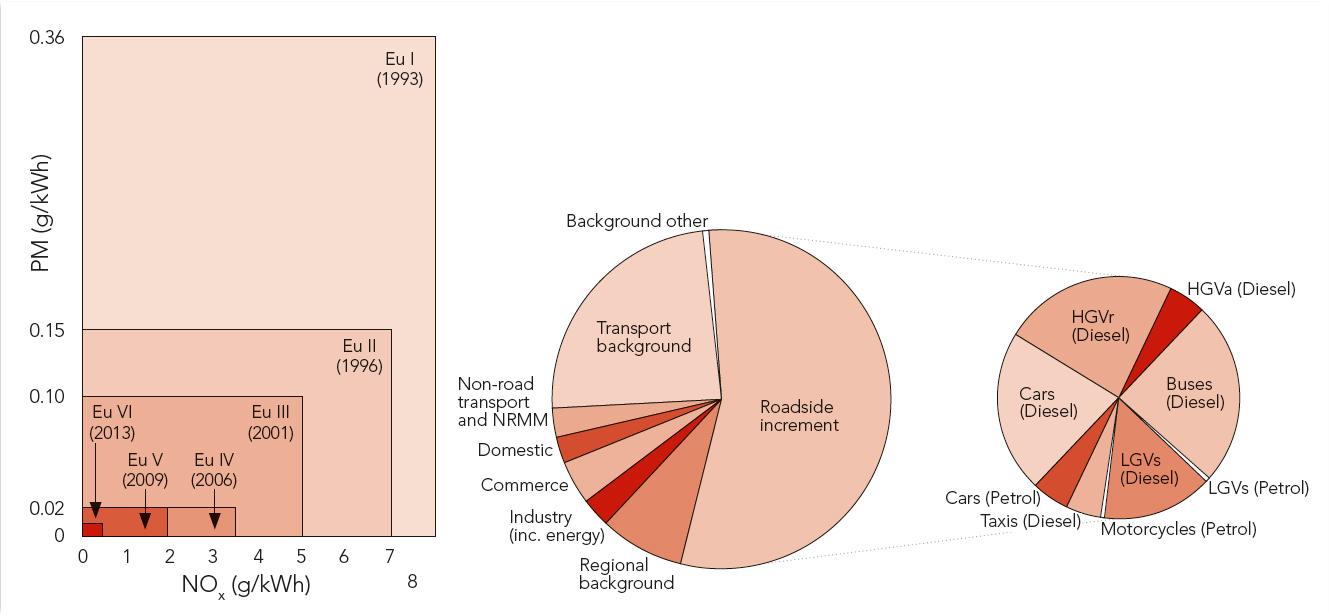

The major concerns are around the emissions of small particulate matter (PM) measuring below 10 microns (PM10), the even smaller PM2.5 and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) which diesel engine vehicles produce in larger quantities than petrol engines. The OECD said diesel engined vehicles can be responsible for more than of 90% of PM2.5 and NO2 emissions in some inner cities and the increase in diesel power could reverse the downward trend in air-pollution related deaths among its 34 member countries.

It says governments need to rethink policies and in particular tax frameworks that may have been introduced to incentivise the use of diesel vehicles as they are up to 30% more fuel efficient and so produce less CO2.

Air quality in cities is also greatly influenced by non-transport related pollution from domestic and industry sources, the local geography or street design and is not confined to large conurbations. Mongolian capital Ulaanbaatar is a case in point. Although it only has a population of 1.34 million, Ulaanbaatar is located in a valley, surrounded by high mountains and was named by the World Health Organisation as globally one of the five worse cities for particulate pollution. The sources of these emissions are coal and biomass combustion in households and heat-only boilers, followed by power plants - transport is far from the highest contributor although the city does suffer from congestion during peak periods (ITS Mongolia is on the case).

More typically, city authorities across the OECD countries and beyond have been frustrated that the tightening of emissions limits for new vehicles is not translating through to lower levels of pollution which has thrown the spotlight on the official test cycles included in the type approval tests.

These tests are designed to test emissions including particulate matter and NOx (which typically comprises 60% NO2). However, according to Nick Molden, CEO of Emissions Analytics, tests like the European Union's Euro 5 standard do not reflect real-world driving such that the NOx emissions from Euro 5 diesel vehicles are typically four times the levels recorded in the official tests. Of the 10 Euro 5 cars in its latest test designed to reflect real-world driving, seven failed to meet the Euro 3 lab-test standard. “If an authority only permitted Euro 5 vehicles to enter the city they may still breach the NO2 limits in the EU's air quality standard,” he said.

That is not to say the road authorities have no influence as Molden explained: “Internal combustion engines work best in steady state operation and therefore minimising stop-start events would have a significant effect on emissions - especially NOx from diesel vehicles.”

Analysis of the company’s second-by-second emissions trace shows a vehicle that has to come to a halt at traffic lights, idles and then moves off and accelerates, emits 35% more NOx than if it passed unhindered through the lights. And while comparative PM figures are not available Molden expects the increase to be similar if not even more marked. This means that the likes of speed to green and green waves can have a significant impact on NOx emissions. "Even if the average speed of those vehicles was only 20mph [32km/h],” he adds.

Easy Wins

The same is also true for heavy goods vehicles and this is an area where Molden feels major gains can be made by authorities working with local businesses and residents to arrange out-of-hours retail deliveries. "Keeping trucks out of peak hour congestion can bring major benefits in terms of air quality and also reduces congestion for those who do need to be on the road at that time."

Elevated emissions levels are also seen in the first 15 minutes after a cold start before the engine and exhaust after treatment have reached full operating temperature. “In an urban setting these would be very short runs, which opens up the opportunity for plug-in hybrids and electric vehicles (with range-extending engines if necessary) that do not go through the warm up phase in this sort of location, thereby delivering a benefit in terms of urban air quality,” he said. In a similar vein he added that there was concern about the result from cooling of exhaust after treatment with the advent of auto stop/start engine technology.

The periodic incineration (regeneration) of particulates captured in the diesel particulate filter sees NOx production double for periods of around 15 minutes but these figures omitted from the official Euro 5 lab tests. The latest Euro 6 standard sees diesel vehicles fitted with selective catalytic reduction which, in general, he sees as a major step forward although the results from the 'real-life' tests are again variable, partly as a result of different dosing strategies

While it is clear that petrol engine vehicles are superior in terms of air quality (if not for greenhouse gas emissions), they are not a panacea. In particular there is concern about the potential for sub-2.5 micron particulate emissions from direct injection petrol engines and those running on compressed natural gas.

Limiting access

To counter some of the biggest air quality problems of any city, officials in Beijing have introduced a scheme to limit the number of vehicles entering the city by dividing them into five groups based on the final letter of the number plate. Mexico and Athens have used odd/even registration plate numbers to limit access and earlier this year Paris used similar tactics during a period of very high pollution.

While the number plate method can be quickly introduced in the event of a high-pollution incident, the measure is far from the most efficient form of improving air quality as consultant Lucy Sadler from the Urban Access Regulations website points out: “The odd/even system is not the most effective measure to reduce pollution or traffic. It’s inconvenient for drivers and does not differentiate between trucks, buses, vans, private cars or two wheelers or give priority to users of lower emission vehicles. And in the longer term households are likely to have two vehicles, one with each type of number plate so that there is little traffic reduction.

“Low emission zones and some of the other access regulation schemes, on the other hand, can be tailored to address the problems individual cities face.”

In Europe and beyond low emission zones (LEZs) are a more common way of combating air quality problems. These allow particular vehicle types to be targeted or excluded; low emission vehicles discounted and older, more polluting ones banned or surcharged.

Urban Access Regulation Schemes (ARS) are wider in scope and are gaining in popularity as they can address more than simply emissions or congestion in isolation. “Many tourists want to visit ancient towns and cities so authorities in those areas have to balance access for sightseers and workers, mail and freight deliveries against the health of those living and working in their cities and the attractiveness of the city,” she said.

“Italian cities have lot of two-stroke powered two-wheelers causing high levels of pollution in many of the old and very narrow streets,” says Sadler, adding that many Italian cities are using LEZs or other types of ARS to target these vehicles.

Enforcement of most permutations can be accomplished by using automatic number plate identification (ANPR) using systems that can also accommodate varying operating times during week days or weekends, or access for deliveries out of peak times.

However, Sadler points out that in some countries ANPR can this politically difficult or too expensive to implement. She highlights the German LEZs where ANPR is not politically possible and windscreen stickers are issued to vehicles meeting the relevant emissions standard. Vehicles without the sticker may not enter the city. “The ‘public display’ of conformity can bring with it a degree of peer pressure to use a less polluting vehicle,” she said.

To support public authorities with these schemes, the European Commission provides free membership to the CLARS (Charging, Low Emission Zones, other Access Regulation Schemes) Network. There is also a public website to provide individual motorists and fleet operators with information on the various schemes around Europe, in order that drivers know they will be entering a restricted area and can ensure they comply with the requirements.

Variable exposure

Pollution may be inevitable in inner cities but research by King’s College London has shown that an individual’s exposure to particulate matter varies widely, and somewhat counter-intuitively, depending on their mode of transport. To obtain real-life data, volunteers including a cycle courier, an ambulance driver, a secondary school pupil, a pensioner, an office worker, a home worker and a nursery toddler wore air quality monitors for the day in London.

The published results show comparisons between motorists, cyclists and pedestrians as well as those travelling the streets all day with those who work inside. Especially interesting were the results of the ambulance driver and the cycle courier (who both spent the day travelling around London) and showed the ambulance driver’s exposed to particulate matter was up to three times higher – up to around 60µg/m3. According to Dr Ben Barratt, senior research fellow of King’s Environmental Research Group, this is because particulate matter concentrations can become trapped inside a vehicle. He also suggests the same thing can happen in narrow streets and increases concentrations of pollutants in areas such as Putney High Street.

Another unexpected finding was that the school pupil was exposed to far less particulate matter during the walk to school in the morning that when travelling home in the afternoon by bus. The bus took a different route and the journey was much quicker so the duration of exposure was shorter.

Sharing society

As was repeatedly pointed out at the recent ITS World Congress, most people only use their cars for a small fraction of the day and gives rise to the notion of car sharing and ride sharing and the new mantra of ‘Sharing is the New Owning’. Certainly one school of thought is that beyond safety, the biggest gains available from autonomous vehicles is likely to come from the wider use of sharing.Certainly the idea has captured the attention of the likes of Ford while Hertz has launched car sharing services on three continents.

The UK has one of the highest car club membership rates and this is expected to reach one million just in London by 2020. Of the London's 33 boroughs, 25 already have car clubs.

To operate effectively in inner city areas car clubs require good will from the local authority to provide preferential and dedicated parking spaces in places that are accessible to potential users. In return the availability of a car club can lead to lower vehicle ownership and the vehicles provided generally comply with the latest emissions standards and are fuel efficient.

In the London Borough of Hackney carpooling company

Car club members generally fall into two main segments: younger, urban drivers between 25 and 45 who want easy access to a car without the hassle of owning one, and families with one car who need access to a second vehicle.

Zipcar said its members tend not to commute by car and get around using public transport; 70% of its members in London use a bus at least once a week while a third cycle at least once a week. They only drive one seventh of the short journeys (less than 5 miles) undertaken by car owners and only use a car for specific journeys.

The company's London fleet is almost 100% Euro 5 (or Euro 6) compliant. It said its vehicles’ carbon emissions are 33% lower than the national average it also provides a range of vehicles for small companies to use by the day or hour.

Members get secure access to a vehicle either using their membership card or via a mobile app and its cars are equipped with tracking technology to help a member locate a car or find one that may be lost or stolen.

As a vehicle takes up the same amount of road space and burns a roughly equivalent amount of fuel if it is carrying one person or four, ride sharing has an even greater potential to reduce pollution and emissions in cities and elsewhere.

French ride sharing company BlaBlaCar connects travellers wishing to cover long distances– typically over 300km – and share the cost through its website. Drivers publish an advert outlining their journey (departure point, destination, date, time…) and the number of seats available. Potential passengers search the site and come up with a list of drivers planning to make the trip at a convenient time. They also get additional information such as the driver’s gender, smoking/non-smoking and the number of reviews the driver has received.The company says it reached nine millionsubscribers inone year and now accounts for 95% of carpool adverts in France.

Out of town

Even outside of urban areas air quality can be a problem and reducing the speed of vehicles can help but, according to Nick Molden of Emissions Analytics, the main effect is on CO2 emissions rather than particulates and NOx. If the speed is reduced from 112km/h to 96km/h (70mph to 60 mph) the real world effect could be an average fuel economy increase of 22% (15% to 34% depending on the make and model) leading to a 19% fall in CO2 emissions.

“Particulate and NOx emissions may fall because less fuel is being burned but they do not vary that much in steady-state operation, it is during acceleration that these tend to peak,” he said.

Smoking kills more

Smoking tobacco exposes users to far greater levels of pollution than travelling through city centres and according to the World Health Organisation half of tobacco smokers will die of smoking related diseases.

In its factsheet updated in May 2014, the WHO stated that tobacco kills nearly six million people each year - more than 600,000 of which are the result of non-smokers being exposed to second-hand smoke. In the absence of urgent action it said the annual death toll could rise to more than eight million by 2030.