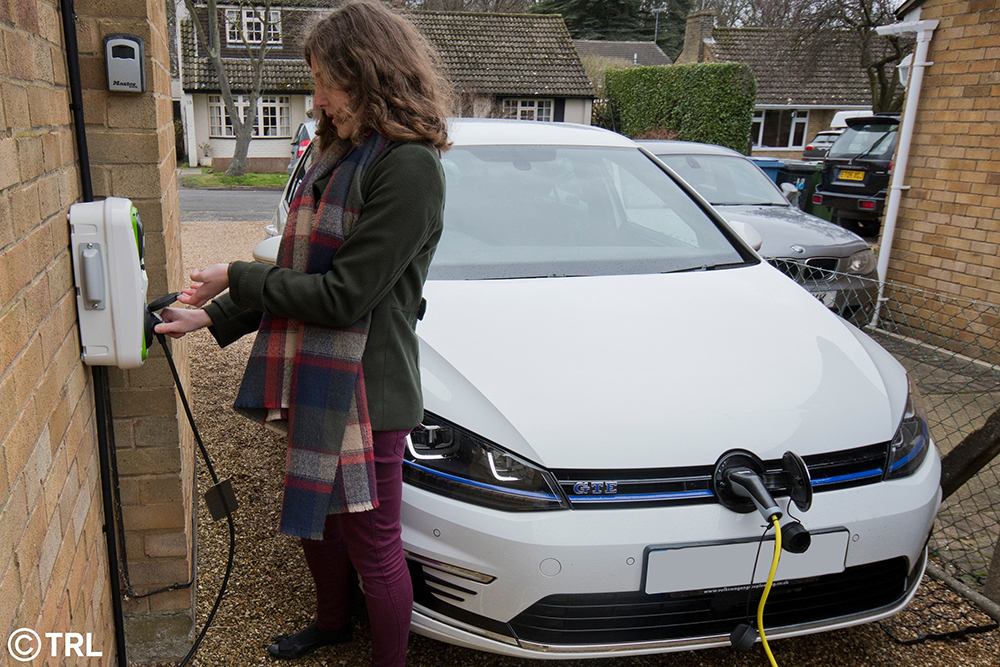

Electric vehicles (EVs) sound great but there are serious concerns about the capacity of existing grid networks to cope with demand. After all, no-one is going to buy in to EVs if you have to make a choice between charging your car or heating your home. Help may be at hand, according to a study led by TRL. Managed charging (MC) can shift EV charging demand in the UK away from peak times. MC aims to shift plug-in vehicle (PiV) charging load to times - such as overnight - when other demands are low.

TRL found that, after experiencing some form of MC, the vast majority of people would be happy to switch to it. This research, part of TRL’s Vehicles and Energy Integration (CVEI) project, set out to investigate the challenges and opportunities involved in transitioning to a low carbon fleet.

Speaking to ITS International, Dr Neale Kinnear, head of behavioural science at TRL, says the Energy Technologies Institute which funded the project identified a “big problem if drivers suddenly bought EVs and plugged them in at 5pm”.

Holistic model

He reveals that the project set out to create a “holistic model” of customers, vehicles and the energy system so you could plug in some data from “different policy scenarios” and get an output of what the future would look like.

“In doing that, we identified that the problem is we don’t know how quickly consumers will buy the vehicles and we don’t know what they will do with them once they have them,” Kinnear explains. “We also don’t know if - rather than spending billions on energy in the streets to upgrade all our network - could we just get consumers to charge at different times through smart charging?”

The project provided mainstream consumers (petrol or diesel vehicle owners) with eight weeks’ experience of using and charging a battery EV (BEV) or plug-in hybrid EV (PHEV). These trials explored consumers’ charging behaviour and response to approaches for the management of PiV charging demand.

Kinnear explains that the trial introduced conditions which included introducing a charge point cloud system that allowed participants to control charging via an app.

“Another condition was that they could charge as they like while another incentivised them to charge at the time of use, like Economy 7,” he continues. “Finally, they were asked to enter into the system when they need their car, and how much charging they want, and to hand over to the energy supplier to charge the car at a time that suits them.”

Charging incentives

Participants divided into the user-managed charging (UMC) group were incentivised to charge at times when electricity demand was low - while those allocated to the supplier-managed charging (SMC) group allowed the energy supplier to control the timing of the charge.

Both groups were incentivised through a system where points earned from home charging could be converted to money at the end of the trial. A control group which did not experience MC was not given incentives to charge in a particular way - but could earn these points by driving a minimum of 50 miles per week.

“The incentives were not massive, so it showed that people were willing to engage in this system and to boost the charging,” Kinnear beams. People “really engaged” with SMC, where the charging largely happened overnight, he adds.

TRL’s report - Mainstream consumers’ attitudes and behaviours under Managed Charging Schemes for BEVs and PHEVs - shows participants in the control group usually charged at home in the late afternoon/early evening (3pm-8pm). It reveals a peak in weekday charging between 5pm-6pm for PHEV participants and 6pm-7pm for those with BEVs. At weekends, a greater share of charge events started earlier in the day. This shows that when charging is not managed, mainstream consumers are likely to charge in the early evening – at exactly the time, in other words, when electricity demands are high.

Compared with unmanaged charging, the proportion of home charge events starting between 4-7pm was more than halved in the UMC and SMC groups. Most of the charging was shifted to later in the evening (UMC) or overnight (SMC).

Behavioural shift

Aside from the behavioural shift in energy demand, Kinnear insists the other “real big positive” is that people liked engaging in the trial (see opposite, TRL study: the results).

“If they were to own an EV after the trial they would choose one of these conditions, they would choose to have managed charging rather than controlled charging. Even the people in the control group who just experienced living with an EV for two months, said they would choose one of these conditions, so there’s an appetite for it that we did not realise.”

According to Kinnear other findings showed that consumers want 200-300 miles of range from a fully EV to consider replacing their main car despite driving no more than 30 miles in a typical journey.

“We found a lot of time you are certainly not charging from zero and a lot of the time people are charging from 50%+ battery level still remaining,” he adds.

Looking ahead, he believes the industry is moving at a fast pace with start-up organisations offering technology which could open up opportunities for the market like those without off-street parking and the ability to control charging through apps.

“Things are moving in the right direction, but whether it’s moving fast enough for climate reduction targets is another question and that may require policy and stimulation and encouragement for both industry and consumers.”

Kinnear recognises the UK government is helping to speed up the process with a range of measures, but emphasises “the roadmap we have outlined highlights that we will need to continue because the current rate of adoption of EVs to replace internal combustion engine vehicles is not fast enough to meet targets”.

Other consortium members include Baringa Partners, Element Energy, Cenex, EV Connect, the Behavioural Insights Team, EDF Energy and Shell.

However, he maintains that EV adoption will increase once the price of EVs comes down to the equivalent of petrol and diesel vehicles and manufacturers can offer a broader range.

“Then it’s about the experience of having one and owning one and that’s where public charging network, ease of use and interoperability of charge points and the reliability and accessibility of them. Once that becomes a positive experience, then you start to open the market,” he concludes.

TRL study: the results

Averaged across the groups, just under 90% of participants indicated that they would choose either user-managed (UMC) or supplier-managed (SMC) charging over unmanaged charging whether they had a battery EV (BEV) or plug-in hybrid EV (PHEV).

Additionally, control group participants who had not experienced managed charging during the trials expressed a preference for managed over unmanaged charging. These participants were substantially more likely to choose UMC or SMC.

Other results showed that the value BEV participants attached to MC tended to be higher if there was nearby public charging – and this increased the nearer the public charging was to their homes.

The study found participants were more likely to choose an MC scheme the greater the expected annual cost savings but increasing the cost of charging at peak time reduced the scheme’s attractiveness.

More than half of participants across the whole sample indicated that the availability of a UMC or SMC scheme would make them at least “a little more likely” to purchase a BEV or PHEV.