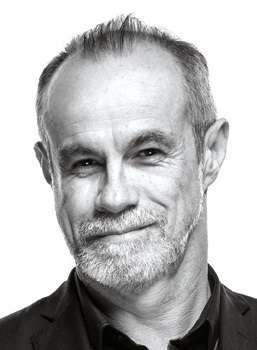

If you’re an urban dweller, Carlos Moreno gives you plenty to ponder. The professor at the Panthéon-Sorbonne in Paris came up with the 15-minute city concept, which suggests that everything you need for daily life – work, school, shops, healthcare, entertainment and so on - should ideally be within a quarter of an hour’s walk or cycle ride from where you live.

This means that, instead of lengthy commutes and traffic jams, cities should be rethought around four principles: ecology (green and sustainable), proximity (as described above), solidarity (creating links between people) and participation (actively involving citizens in the transformation of their neighbourhood). Urban areas should adapt to humans – not the other way round. Maybe ‘human smart cities’ would be a good way of thinking about them.

“Those of us who live in cities, big and small, have accepted the unacceptable: that our sense of time is warped because we have to waste so much of it,” Moreno argued in a Ted talk a couple of years ago.

“First we need to start asking questions that we have forgotten. We need to look harder at how we use our square metres: what is that space for? Who is using it and how? We need to understand what resources we have and how they are used. Then we need to ask what services are available in the vicinity – not only in the city centre, in every vicinity: health providers, shops, artists, markets, sport, cultural life, schools, parks. We also have to ask ourselves how do we work? Why is the place I live here and work is far away?”

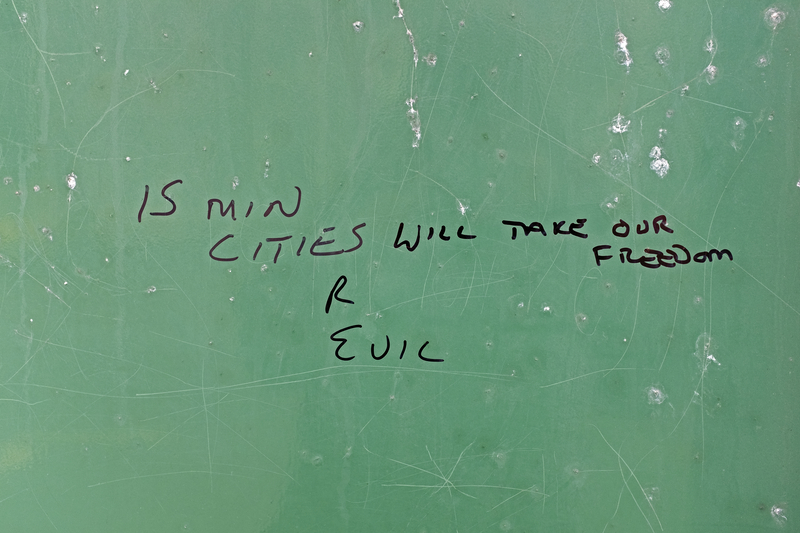

‘Socialist conspiracy’

All of this seems hard to argue with. Cities can be difficult to get around. We can surely do things better – the desire for smoother urban mobility is at the heart of the ITS industry, after all. Moreover, urbanist academics such as Moreno are paid to think exactly about how cities can be better organised: safer, cleaner, more efficient, able to create more economic opportunity, easier to live in, and so on. Transport emissions are a proven health issue and mainstream scientific opinion is that we need, as a species, to restrict our use of fossil fuels to stave off climate disaster. This is not particularly controversial.

Some surprise, then, when the 15-minute city concept found itself at the centre of a storm which involved protests on the streets: it was called a socialist conspiracy; it was argued that proponents want to restrict people’s freedom; it is an insidious attempt at government mind control; you won’t be allowed out of your 15-minute ‘zone’ without a biometric passport; it would be like The Hunger Games, and so on, and so on.

Speaking on the phone to ITS International, Moreno reveals he was amazed at this response to his urban planning concept. “I was totally surprised,” he laughs in disbelief. “I never really imagined that it was possible to relate the 15-minute city – as a humanistic, urbanistic concept proposed for developing more social interactions, new economic models, more sustainability, more capability for using public space differently – to this idea.”

Conspiracy theorists did not see it that way. “The conspiracy mongers are totally convinced that climate change doesn’t exist,” Moreno continues. “They are, by definition, climate deniers. They also consider that digital identity is a kind of control and, after Covid-19, that there is a new way of implanting 5G chips to control each one of us, our individuality.”

There is also a perceived attack on automobile ownership. “For the conspiracy mongers, the 15-minute city is related to the reduction of freedom – particularly restrictions on using individual cars,” Moreno says. “The storytelling of these conspiracy mongers is to relate the 15-minute city to the Covid lockdowns and the idea that we wanted to prepare people for a ‘climate lockdown’. In reality, this is totally insane, it’s a manipulation, without a concrete link to the concept of the 15-minute city. Unfortunately, it’s creating fake news, fear and misinformation.”

Dark times

And it’s also no joke. Moreno has received “a lot” of death threats. “I think this is a sign of the dark times for scientists because in reality I am not the only scientist to receive death threats.” It has happened to many colleagues involved in work on climate change, he explains. “Some people, in reality, don’t have limits.”

Even when not malign, the misrepresentation of 15-minute cities goes against what Moreno has explicitly put on record. In his Ted talk, he insisted: “Don’t get me wrong: I’m not angling for cities to become rural hamlets. The urban life is vibrant and creative; cities are places of economic dynamism and innovation. But we need to make urban life more pleasant, agile, healthy and flexible. To do so we need to make sure everyone – and I mean everyone – those living downtown and those living at the fringes – have access to all key services within proximity.”

This is an important point, he tells ITS International. “A lot of people have said that this is a return to the village of the 19th century - but I have said that the 15-minute city is not a collection of rural hamlets.”

Communications – particularly the internet – means there is no comparison in the 21st century. “With the 15-minute city we wanted to reconcile our capabilities for reducing our CO2 footprint – and for that we need to reduce the long commute in the individual car.”

Greater proximity

Also, cities need to optimise the use of existing infrastructure, particularly buildings, Moreno says, so that they have more than one purpose. “At the same time, we need to have a multi-connected city: we need to use the new technologies for developing more proximities,” he adds. “Proximity in cities is not only [about] the shortest distances. That is a big difference with the last century: there are lots of new kinds of proximity. For example, I could be in my home and have a nicer, greater proximity with friends who live in São Paulo or in Bogotá or New York. This is not a physical proximity but we have completely digital opportunities for creating activities or exploring convergences.”

The 15-minute city is also an opportunity for looking at hybrid forms of working. At one level this means interacting with public spaces, commerce and jobs in your area – and at the other, using digital technology to create new economic and other opportunities which require you to travel less.

That said, it won’t be possible (or even desirable) for everyone to switch to a job which enables a digital – rather than physical – presence. But Moreno cites a Boston Consulting Group survey which found that 68% of workers who could not work remotely “considered that a long daily commute is one of the most relevant factors in the degradation of the quality of life”.

A proportion of people will always need to commute, says Moreno: “In that case, we could offer better quality of services for people using public transportation.”

Paris is perhaps one example of somewhere on its way to being a 15-minute city – not least due to the political will of the city’s mayor Anne Hidalgo – but Moreno is confident that there are others, particularly within the C40 cities group, an international network of city mayors who emphasise sustainability.

In Italy, he sees Milan, Rome and Bologna as “totally committed” to the concept, along with Barcelona (with its ‘superblocks’) and Valencia in Spain, Lisbon in Portugal, Seoul in South Korea, Chengdu in China, Buenos Aires in Argentina and Bogotá in Moreno’s birth country of Colombia – not to mention Seattle and Colombus in the US, and Montreal in Canada. Moreno also namechecks the Scottish government’s support for a ‘20-minute neighbourhoods’ policy to alleviate climate change.

Covid-19 has proved, worldwide, that it’s possible for many of us to change our work-style – and Moreno says people have found “new useful time” as a result.

“A lot of people have discovered the benefits of the reduction of a long daily commute,” he suggests, “finding one or two more useful hours for increasing the personal, individual or social or family quality of life”.