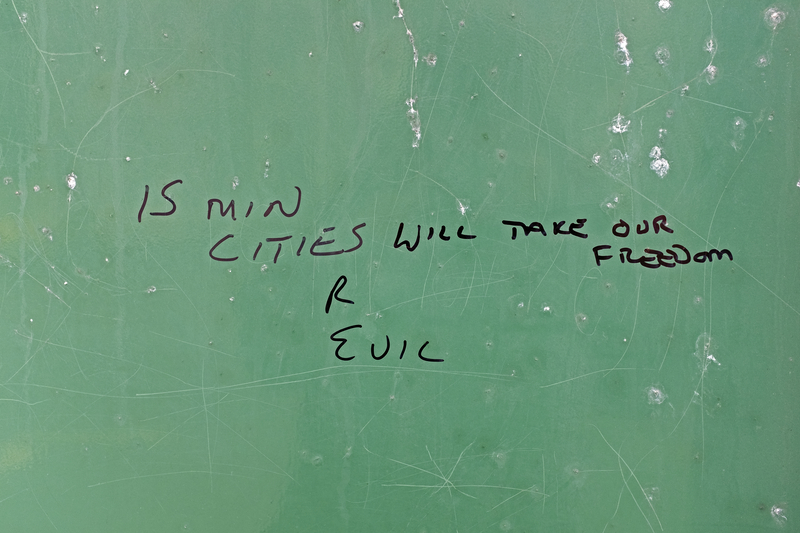

There’s a plot by an unseen cabal to usher in digital prisons that will stop us all from travelling more than a few hundred metres from our homes. It’s called the 15-minute city and it’s coming to a neighbourhood near you.

That, at least, is the message you may take away if you inhabit certain parts of social media, or if you had visited Oxford, UK, to witness protestors conducting a mass leaflet drop against a new traffic scheme in early 2023.

The famous English university city has been seeking solutions to congestion into and around its narrow historic streets for decades now. Its latest plan is a trial of six traffic filters enforced by bollards and numberplate recognition systems - all designed to reduce traffic, make bus journeys faster and make walking and cycling safer in some of the most congested city areas. Some private vehicle journeys will be limited but will be permitted up to 100 days a year for local residents and with a long list of exceptions.

Objections to the scheme are not just a storm in a social-media teacup, however. Residents have taken matters into their own hands, systematically removing bollards and pouring cement into holes to sabotage repair. Clearly the scheme has specific problems for residents that need to be addressed.

This all matters to the city’s longer-term plans to be a fully-functioning 15-minute city by 2040 - and to those cities with similar aspirations.

The violence of the reaction to what amounts to a fairly modest scheme from a range of commentators - including a politician from the UK’s ruling Conservative party and various minor celebrities - surprised Oxfordshire County Council, which introduced the trial, and Oxford City Council, which supported it.

The councils were alarmed by the outcry and by threats made against officials. Similar proposals – for example, in Edmonton, Canada - have also come under attack and the idea of 15-minute cities has been challenged by a range of influencers around the world.

The concept then is, to put it mildly, suffering a bit of a PR problem right now. How did we get here and what do planners, municipalities and mayors need to do about it?

Before we get to that, a short history lesson may be in order.

Back to a less congested future

Popularised by Carlos Moreno, a professor of urban planning at Panthéon-Sorbonne University in Paris, the 15-minute city concept emphasises proximity, walkability, bikeability and public transport in creating liveable and sustainable cities where people can access all the basic necessities of daily life within a 15-minute radius of their home.

But it has deeper roots that can be traced further back – for example, to American-Canadian journalist, author and urban activist Jane Jacobs, one of the first to argue in the 1960s that cities should be designed at the street and neighbourhood level around the needs and desires of people, rather than being driven solely by the needs of automobiles.

Dutch urban planner Hans Monderman, who developed the concept of shared space, which involved designing streets that were shared by pedestrians, cyclists and vehicles, also contributed to the notion of what makes liveable neighbourhoods.

So how did such a fractal notion of what makes a place liveable - which arose from close observations of how humans flourish in cities - come to be identified as a top-down imposition on our liberties and a goose-step away from a full-blown, China-style social credit scheme?

Recent history is undoubtedly part of the answer. Draconian pandemic-driven lockdowns, and their unprecedented restrictions on movement, unsettled many. Fear over the imposition of top-down agendas has also contributed. ‘Build-back-better’, ‘Great Reset’ and ‘Net Zero’ have become totemic phrases; indicators of a coming era of repression in some parts of social media.

Politics has its part to play too. The libertarian end of the spectrum accuses planners of imposing ‘socialism’ by salami slicing our freedoms, one traffic interchange at a time. This may seem absurd but the schemes inevitably bring restrictions and trade-offs and it’s not just extreme claims that are challenging the progress of 15-minute cities.

Space for nuance

Other, more reflective, critiques may be worth pondering before considering how, and where, to make the case anew.

The misgivings of local residents about specific elements of low-traffic neighbourhoods are perhaps a more potent factor. “I don’t condone it,” said one elderly female resident interviewed by local news channel ITV Meridian regarding vandalism of the Oxford scheme. “But they are not listening. There is no democracy in Oxford. That’s where the anger is coming in – that, and people being stuck in traffic.”

They are not without academic supporters. Sociologist Richard Sennett argued in his book, Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City that the 15-minute city concept can fail to capture the complex and multifaceted nature of city life and argues for a nuanced approach to create liveable and sustainable cities. The model may work well in dense, walkable cities like Paris, but may fail in suburbia or Los Angeles-style sprawl. Restricting travel into vibrant city hubs, meanwhile, is not even necessarily desirable.

Australian sustainability professor Peter Newman warns against planners placing too much focus on the physical form of cities, at the expense of the social and political factors that shape urban life. Has the rise of home working, for example, created its own momentum towards 15-minute cities as tele-commuters stay put?

Others point out that 15-minute cities may perpetuate existing inequalities, in assuming that all residents have equal access to local resources and opportunities. Access to cars may be a necessity to some disadvantaged citizens with little labour choice, doing jobs far from home. The gentrification resulting from 15-minute cities may drive up real-estate values and with it economic inequality.

With such objections all in mind, how do proponents of 15-minute cities advance their case today?

It’s possible, of course, to argue that they make their own case. An obvious example is the success Paris has had with its interpretation of the ville du quart d’heure and the political capital that its mayor Anne Hidalgo, who made it the centrepiece of her successful 2020 re-election campaign, has garnered as a result.

Positive outcomes

While the evidence supporting 15-minute cities is still developing, early research suggests that this model of urban development can have a range of positive economic, social, environmental and health outcomes.

This may best be communicated in terms of the freedoms and possibilities they open up, including:

Economic: The concentration of amenities and services in compact neighbourhoods leads to more vibrant and diverse local economies that are more resilient to economic downturns.

Social: We are a social species and the chance for locals to rub shoulders, connect with neighbours and engage in local activities is a clear benefit. Walkable neighbourhoods can also be more inclusive and accessible for people of all ages and abilities, including those without cars.

Environmental: The freedom to move on foot by bike or public transport, cleaner air and more habitable streetscapes are obvious advantages.

Health: The movement a 15-minute cityscape encourages is ‘nutritious’, reducing sedentary behaviour, and cutting the risk of chronic diseases such as obesity and heart disease.

The specific lessons of Urban Vehicle Access Regulations (Uvar) schemes may also be worth studying, as ITS International recently explored. Successful implementations by Uvar planners will often carry across to schemes related to 15-minute cities, including the need for careful messaging to secure local support. Fair, user-friendly and non-discriminatory enforcement is another key to effective implementation.

Clear communication and a close understanding of genuine local concerns is also a must. Perhaps part of the PR approach here may be to lay out clearly that 15-minute cities are not a suitable spatial fix in every city - or even in every part of the cities where they do work. In short, they must be seen as part of wider urban improvements designed to benefit all and dependent to a large extent on the consent of residents.

Such approaches may not quell the wilder conspiracy theorists, but they may help win the hearts and minds of those who matter most.