In the USA, congestion mitigation and improving mobility have often focused on network improvements, increased road capacity, improved public transport, high-occupancy toll (HOT) lanes or ‘express lanes’ and ITS measures – all of which require political capital and major funding.

Nowadays, political capital is as hard to obtain as funding because more political leaders are recognising the decline of fuel excise tax in transport funding and the impact of inflation of materials and services. In the USA, fuel economy of both cars and trucks has improved by 54% since 1975 and by 2030 the average light vehicle fuel economy is expected to be between 35 and 55mpg and around 39mpg for the entire US vehicle fleet. This will result in a further decline of revenues between 40% to 60%.

This decline in revenue is being accelerated by fuel-efficient hybrid and electric vehicles that may comprise 30%-35% of the US fleet by 2035 (by which time the sale of new petrol and diesel cars will be banned in several countries). The result is that policy makers are hesitant to risk increasing fuel taxes as at the next election, their political opponents will highlight the futility of the measure because overall revenues will not have increased as promised.

Consequently, the US government is studying alternatives to the gas tax with federally-funded pilots in states including Oregon, Washington, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Missouri, Minnesota, Pennsylvania and Delaware. The aim is to increase transport revenues with a rational and sustainable transport funding policy that works with, not against, environmental policies.

Currently, the states involved with Vehicle Miles Travelled (VMT) – often called road usage charging (RUC) or mobility pricing - are undertaking communications and public information campaigns to explain and demonstrate the benefits of MP/VMT.

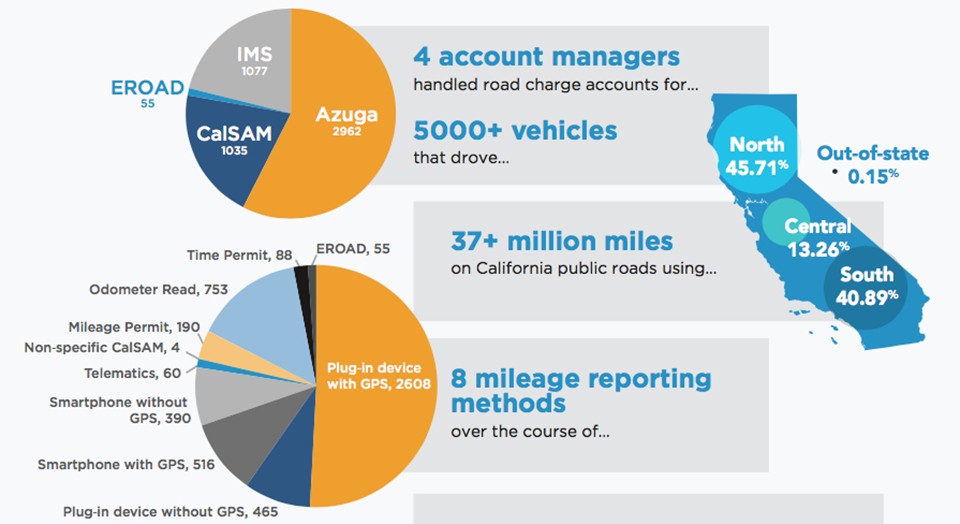

California has recently completed a road charging pilot involving more than 5,000 vehicles (including heavy trucks and fleet vehicles) and Washington State will start a state-wide trial later this year or early 2018. Missouri, Hawaii, Pennsylvania and Delaware are all performing preliminary work and planning demonstrations of road charging pilots.

For US citizens the RUC debate is around whether it should be a federal ‘top down’ approach or a state-sponsored ‘bottom up’ initiative. Current initiatives are at state level because most US transport policies are driven from the states before being adopted as national programmes (as happened with Oregon’s original gas tax in 1919).

Today the federal government levies a uniform 18.4 cents per gallon tax on fuel sales while individual states can add an additional charge on top and retain that revenue for state transportation measures.

The main enabler for road charging is public acceptance so public communications and information are paramount. While many drivers may highlight technology or privacy concerns as the major issues to delay or prevent RUC, in reality the technology required for road user charging is already available. Not only is technology for distance-based charging available, but also the communications, account management and billing systems to create a state or national system.

Oregon has already proved distance-based charging can be done while protecting individual privacy using measures similar to those employed by the banking industry and others. Like many new ideas or concepts, road usage charging has to be carefully introduced, proved to work and shown to be acceptable. As with all fiscal policy, there will be winners and losers. In general, these are clearly associated with the type of vehicle or fuel economy of the vehicle. The benefit of VMT or RUC is that the user or driver can control the charge by the distance they drive. After nine months of testing in California for example, the data suggests that between 80 % and 90% of participants found RUC ‘acceptable’ and between 70% and 80% said it was ‘fairer’ than the gas tax. These end-of-testing results indicate that hands-on experience, proper communications, and public information can dispel pre-conceived fears and positively shape opinions on road charging.

Testing has already identified several workable RUC solutions that divide into technical and non-technical systems and California pilot tested both types. Technical solutions included in-vehicle GNSS, vehicle telematics, and smart phone apps that connect to the vehicle systems and an app that automatically uses the phone to photograph the odometer and transmits the image to log the mileage.

Non-technical solutions included authorised service locations reading the vehicle odometer at specific intervals, pre-purchasing blocks of mileage, or reporting mileage at annual inspections. California is also investigating ‘pay-at-the-pump’ or ‘pay at the charging-station’ options through the Federal Grant Program.

Interestingly, over 80% of participants chose a technical solution.

In another state programme, a variable charge for road usage (determined by the distance travelled) is being combined with the annual vehicle registration fee, which is based on vehicle class.

It is still too early to determine what solution(s) may be the most likely to be adopted. For public acceptability, allowing drivers to select the road charging solution that best fits their usage pattern may be the most acceptable way to introduce a new transport funding concept. This simple market principle has been proven by the pilot tests undertaken to date.

On a personal level, I see road user charging as a replacement for fuel excise tax (to fund general transportation and mobility needs) that complements congestion charging, tolling, HOT lane or express charging and environmental charging. Additionally, RUC provides all drivers with an account and account management to make these other revenue generating concepts more viable.

Rather than having tolled and free-use roads, all roads use would be charged – privately funded ones via a toll, state-funded by the RUC. Tolled roads or lanes would continue to provide shorter and more consistent journey times and drivers would have to consider if avoiding the toll road by taking a more circuitous route was cheaper, as quick, as well as their relative environmental impact.

Consideration of using HOT or express lanes would also be given a clearer focus by the use of road charging.

As many urban schemes and concepts are basically demand management, this can be mirrored by an additional mileage charge for specific geographic areas, time of day or day of the week – and all using the same account management, billing and payment elements. These additional location-, time- or emissions-based charges would incentivise the use of park-and-ride, public transport, walking and cycling. Such a transparent road pricing structure would allow drivers to select the best way to complete their journey, including parking and any public transport transfers.

Overall, these concepts combine and collaborate nicely with each other. While there is no single solution, it is easier to communicate the benefits of RUC (to gain public acceptance) than to convince drivers of demand management through congestion charging and the like. MP/VMT/RUC combined with value added services or Mobility as a Service is a powerful combination to gain public acceptance.