For more than a decade, authorities in Oregon have known of the impending decline in fuels tax income and while revenue increased by more than 5% in 2016, that growth will slow considerably this year and income is projected to start declining in 2020.

The improvement in fuel efficiency and introduction of electric vehicles is good for the environment but means less fuels tax is generated for each mile driven and is leading to a growing divergence in what drivers are paying to use the roads. As

So to prepare for the impending decline in fuel tax revenue, Oregon is piloting OReGO, a usage charge trial in which more than 1,300 volunteers have been paying 1.5 cents per mile through one of three payment methods (with users credited the fuel tax paid at the pump). It is predicted that switching to a road user charging scheme would generate an additional $340 million in gross revenue in the next 10 years compared with the declining fuel tax.

To find out how the pilot is progressing ITS International spoke to Michelle Godfrey, education and outreach coordinator with ODoT. “The first thing to say is that it works,” she says with some enthusiasm.

The OReGO pilot launched in July 2015 and involves cars and light-duty commercial vehicles. In order to evaluate the impact on a cross section of users, the volunteers’ vehicles were divided into three categories: those achieving 0-17mpg (where drivers receive credit for overpaid gas tax), 17 to 22mpg (broadly neutral) and 22mpg and upwards. Drivers in this last group, which accounted for most of the volunteers’ vehicles, are paying slightly more than with the gas tax. While these people pay more than they would in fuel taxes, it is usually only pennies per day. One user reports that in 18 months, she paid an additional $21.60 (or $1.20/month) and her reason for volunteering was to try it, and to pay her “fair share” for using the roads.

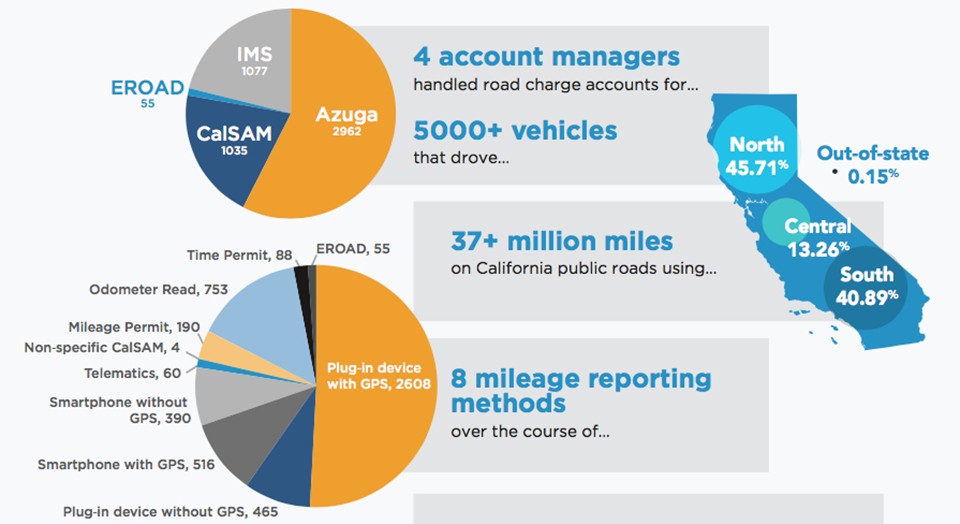

Volunteers could choose between a government-approved and ODoT managed quarterly post-pay account that does not use location technology, or two private sector managed systems.All the options are based on adding a plug-in device which connects to the on-board diagnostic port of the vehicle. To accommodate those with privacy concerns, the enabling legislation ensured volunteers had the choice of both GPS and non-GPS options. However, as the trial progressed, Godfrey says privacy has become less of an issue and while all options had a good participation, the majority of volunteers selected a GPS-enabled option.

She believes this reflects a general trend where people are increasingly comfortable having GPS-enabled devices (such as mobile phones) and feels the added value benefits offered by the GPS options helped overcome lingering resistance. For instance, the Azuga app monitors the vehicle’s health, battery and maintenance needs and it also records trips and events such as hard braking and acceleration – allowing volunteers to review their trips and helping them become smoother drivers, and save fuel.She believes this reflects a general trend where people are increasingly comfortable having GPS-enabled devices (such as mobile phones) and feels the added value benefits offered by the GPS options helped overcome lingering resistance. For instance, the Azuga app monitors the vehicle’s health, battery and maintenance needs and it also records trips and events such as hard braking and acceleration – allowing volunteers to review their trips and helping them become smoother drivers, and save fuel.

“It could also be that people are becoming more comfortable with road user charging and a growing acceptance that the law ensures user’s privacy is protected on many levels,” Godfrey adds. Non-GPS versions do not operate through an app and require minimal driver interaction.

“We are creating a competitive road user charging market for technology providers and are accepting companies wanting to provide these services to give drivers a wealth of choices,” she says.

All the options used the same 1.5 cents per mile charge (equal to the gas tax paid on a typical vehicle with average mpg). If and when it is adopted for all users, that rate could be subject to revision.

In Oregon’s case, its Road User Fee Task Force (RUFTF) has recommended that the programme become mandatory in 2025 for model years 2026 and beyond and road user charging should apply to all new vehicles with fuel consumption rated at or above 20mpg (11.76lit/100km). Oregon already has a weight-mile tax for vehicles that weigh in excess of 26,000 pounds (11.8 tonnes).

The recommendation will go to the Oregon legislature for consideration in the upcoming legislative session (see box) but nothing is likely to be announced this year.

During the pilot, it was evident when drivers with a GPS-enabled device crossed the state boundary and they were not charged for out-of-state miles. However, with an eye to the future, a group called RUC West is piloting a regional system covering California, Oregon and Washington to see how such a system could work and how mileage can be allocated to the appropriate state. As to a nation-wide system, Godfrey says that is still “very far off.”

While public perceptions have changed during the trial, some concerns remain such as per-mile charging being unfair for rural drivers who have to drive long distances. “That’s not the case,” says Godfrey, “because if people are driving longer distances they are already paying more in gas tax.” She highlights a study by Oregon State University that concluded rural drivers would not be negatively impacted by a road charge. It found that rural drivers tend to drive less fuel efficient vehicles and are therefore likely to pay about the same in road user fee charges as they do in gas tax. On the other hand, urban drivers are more likely to drive fuel efficient vehicles and would be likely to pay more under the road charge programme.

The key strength of road user charging is that it is unaffected by increasing fuel efficiency. However, as the RUFTF’s Economic Report highlights, the cost of collection will be higher than with the gas tax – at least in the early stages. With GPS-based systems it would be possible to include differentiated charging to take account of congestion, location or time of day. However, this would require an appropriate legal foundation and would increase system complexity and collection costs.

Godfrey concludes by saying: “Consider this like a utility. The more electricity people use, the more they pay and the use of roads should be subject to the same user-pays principle. Road user charging seems to be the most fair, most universal and most modern way to address the way people drive and to pay for what they use.”

Index linking

It is well documented that political pressures over the last few decades have prevented the gas tax being raised in line with inflation. Many roads and bridges in America are stark reminders of what happens when a road authority’s revenue does not increase in line with rising prices and increased road usage.

Such issues could be addressed at either the state or federal level (or both) but currently the individual states are well ahead of the federal government in regards to road user charging. Godfrey says that any decision about automatic index linking of the road user charge would be for the legislature and has yet to be made. However, House Bill 2017 did increase fuel tax rates and link RUC rates to the increase in fuel tax rates.

“As Oregon DoT, we implement the legislation and don’t take a position about what form that legislation might take. We provide the legislature with the information it needs to make those decisions, which would include evidence about the financial impact of tying or not tying the user charge to inflation,” she says.