A new report on the economic costs of traffic congestion predicts the problem will worsen significantly in future. Jon Masters reviews the figures and some suggested solutions.

New figures on the rising economic and environmental costs of congestion have been published by the US traffic data specialist

The study has its critics. Cebr has had to make some pretty big assumptions in places and as a result some of the numbers may be open to question.

This year’s Inrix/Cebr report looks at the economic and environmental costs of congestion in London, Paris, Stuttgart and Los Angeles and extends the forecasts to 2030, with a further addition of ‘planning time’. This is the extra time drivers allow for their journeys to counteract the uncertainty over the level of congestion they will encounter.

Across all four national economies, the costs imposed by congestion are predicted to rise 46% between 2013 and 2030, from $200.7 billion to $293 billion with a total cumulative cost of $4.4 trillion. The UK is apportioned the greatest increase in cost (up 63% from $20.5 billion in 2013 to $33.4 billion by 2030) and of the cities studied London is expected to have the largest congestion problem with the economic costs increasing by 71%. Los Angeles will be close behind with a 65% rise in impact and Cebr calculate the cumulative cost of the city’s congestion up to 2030 to be $559 billion.

According to Inrix’s European director Matt Simmons, the reasons behind this study relate to Inrix’s work on building up pictures of traffic flow and delay – it publishes an annual scorecard of countries’ congestion and drivers’ ‘hours wasted’ in traffic delays.

Simmons says: “We wanted to look at what the future of traffic congestion might look like, what its effects may be and what that might entail.

“National economies are usually the biggest driver and the link between congestion and economic growth is important. So we aim to highlight that to show [how] investment in ways of reducing congestion have a high value.

“Roads are not always top of government agendas. For us it’s about encouraging innovation and technology and generally promoting cost-effective ways of reducing traffic congestion,” he says.

Methodology

Cebr derived congestion costs from traffic growth forecasts, Inrix’s index of time wasted in stationary traffic, and figures on the costs resulting from this wasted time. The Inrix Index is calculated as a percentage increase in journey time over free-flow conditions. Cebr economist Shruti Uppala says calculation of traffic forecasts was treated with a “rigorous methodology”, using UK Department for Transport (DfT) elasticity values for the three main demand drivers: population growth, GDP per capita and fuel costs.

However, Cebr used the DfT’s traffic forecasts that use complex back-analysis to reach a current rate of growth, which is then extrapolated at a constant to whichever end date has been chosen. This process means the DfT’s traffic predictions show a 55% increase in UK traffic volumes between 2010 and 2040 despite the national statistics showing a marginal decrease in traffic during the past three to four years of economic recession.

Sian Berry is roads and sustainable transport campaigner for the Campaign for Better Transport. She says the Cebr report is based on “dodgy” forecasts and puts unnecessary pressure on governments to build new roads. “The UK’s national transport model indicating a 55% increase in traffic is ridiculous given that the actual national trend has been downward. The population is growing but that’s not equating to the sort of increase in car use the DfT is predicting. People are using public transport and walking and cycling more,” Berry said.

Mix of measures

Simmons is standing by the Inrix/Cebr report, which concludes that authorities pursue a mix of measures to mitigate congestion, including investment in public transport and technology such as real-time traffic management. He said: “I think there is general agreement on the conclusions, and the report is not intended to be taken as a statement on this is how it will be.”He hopes the report will help push the debate up the agenda.

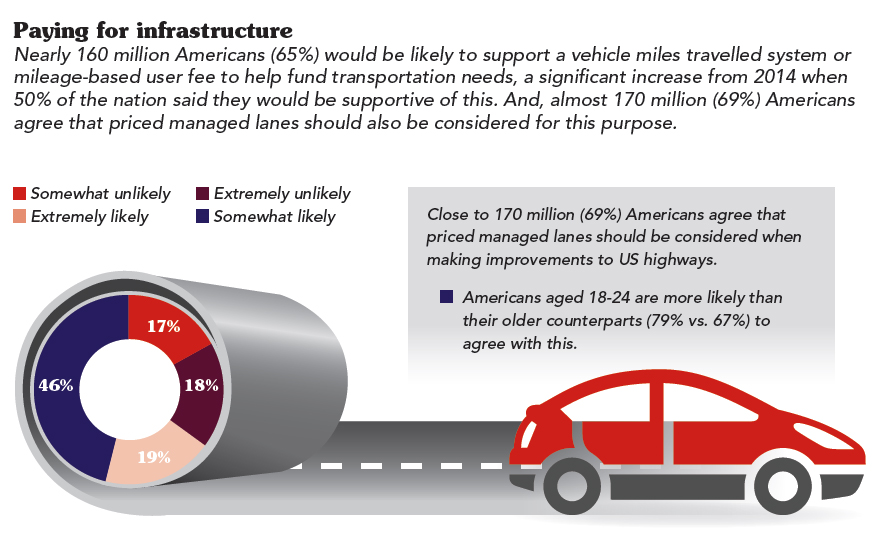

So what are authorities doing, or hoping to do, to tackle the problem? Berry is in favour of national road pricing, which she says makes sense for regulating traffic flow and raising funds for public transport. Politically, however, the UK has kicked this idea into the long grass.In response to the Inrix/Cebr report, a DfT spokesperson said: “Improving road capacity to meet future demand is a crucial part of the government’s long-term economic plan. We are investing £24 billion in England’s strategic road network up to 2021 – the biggest upgrade in more than 30 years.”

This level of investment is unlikely to eradicate traffic congestion, only ease some of the worst bottlenecks. As with many other authorities globally, the

Responding to incidents is the Agency’s overriding priority and according to its traffic management director Simon Sheldon-Wilson, there are usually about 6,000 live lane incidents per month on its network and less than 10% require non-Agency emergency services.

“Our focus is on responding to and clearing incidents as quickly as possible,” he says.

It is now measuring average incident duration and collating data to reduce incidents and cut the clear-up time. For instance, it has been identifying where, when and why there is a high likelihood of trailers overturning, then giving owners preventative advice, says Sheldon-Wilson.

Inrix has been helping the UK and other agencies by enhancing data on traffic flows.

The US has already seen the introduction of physical and technological congestion reducing measures, such as managed high occupancy vehicle (HOV) lanes. According to Inrix’s marketing director Jim Bak, a study of the effects of HOV lanes in the Los Angeles area have shown they resulted in a 6-7 minute improvement in journey time.

“The HOV lanes have been criticised as a waste of billions of dollars. They can’t be expected to solve the problem in isolation and the initiative has achieved a slower build up and a quicker end to the peak period. The local agencies are now trying to do more with bus and transit operations to augment management of traffic,” Bak says.

Several HOV systems in the US have evolved into express lanes, with tolls fluctuating in response to traffic flow to regulate demand and keep traffic in the express lanes moving at all times. This is about as close as authorities have come to real-time traffic management, but involves adjustment of tolls on only a small number of discrete sections of interstate.

More generally, authorities have been augmenting their historic traffic data to better understand traffic patterns. “Evolution to real-time analytics is the next stage, but no-one has really done that yet,” Bak says.

Vehicle manufacturers are also interested in using real-time data, he adds. Inrix’s technology is now in BMW’s i3 and i8 electric vehicles. The resulting Intermodal Navigation system is claimed to be the first in-car service to integrate local public transport connections into journey planning.

The service monitors real-time traffic conditions and will navigate the driver to a faster alternative mode of transportation when major road congestion occurs. “This is a good system, but it needs to have real-time information on train movements for it to be really effective. The in-vehicle system will then be able to navigate the driver to meet a train just as it arrives,” Bak says.

Audi has demonstrated an in-vehicle system to help drivers hit a green light at every intersection. The Traffic Light Online system uses a broadband connection to gather signal timing data and advise drivers on how to moderate their speed.

“The benefits of this sort of system are smoother traffic flow, so less congestion and reduced fuel consumption and emissions,” says Audi of America corporate communications manager Brad Startz. “In Germany it has been estimated that 900 million litres of fuel would be saved if the technology was widely available.”

The difficulty with Traffic Light Online is inconsistency of data. Not all authorities make their traffic light timing data freely available. Audi of America also found lights frequently stuck on ‘ambulance override’ mode, so timings were out of sync with communicated data.

However, Bak says real-time data is the technological goal to enable Authorities to respond quicker and allow drivers to make better decisions. “The information drivers get in their vehicles on public transport could transfer to a mobile phone app as they park and walk on foot, with walking directions and train times. If we can do things like this then we can make networks work better.

“We’re not there yet, but we’ve certainly made a good start.”