Low emission zones and heavy goods vehicles’ access to city centres may at first glance appear attractive but how effective are such controls? Jon Masters reviews emerging trends across Europe.

Around 1,700 European cities have implemented low emission zones (LEZs) and in addition some have restricted city centre access for heavy goods vehicles (HGVs). Even those that restrict HGV access, such as Paris and Rome, allow exemptions at certain times and for particular classes of vehicle. But with what effect?

If better air quality is the principal aim – and for the majority it is – a cursory examination of results can be gathered from data of the Soot Free for the Climate campaign. This is being led by the German federation of environment and nature preservation Bund, supported by the EU Environmental Bureau. One stand-out result is that of Rome, which as some of the most stringent of LEZ controls, ranks low down on the Soot Free Cities (SFC) league of 23 European cities.

Conversely, SFC’s top ranking city, Zurich, does not have an LEZ but has scored highly by using other tactics to reduce air pollution. According to SFC, Zurich lacked the statutory powers to introduce an LEZ and was unable to gain regional government support to enact the necessary legislation.

However, Zurich tops the European ranking (ahead of Copenhagen which has an LEZ for HGVs) as a result of its comprehensive air quality strategy, high city centre parking charges and very good public transport. This is complemented by strict controls on emissions from public sector fleets and diesel engines on construction sites.

Effective measure?

Rome, which is 21st in the SFC list, has an LEZ for all vehicles in its city centre and two further concentric bands spreading out from the centre. HGVs access is restricted at various times for all but the cleanest Euro 6 diesels and hybrid engines, but according to SFC, Rome’s system falls down due to a lack of enforcement.

Paris (eighth in the list) introduced a new LEZ last year covering all vehicles inside the city’s main outer ring road. A first phase banned lorries and buses not meeting the old Euro I emissions standard. By 2020 further phases will progressively exclude access for all vehicles up to the Euro IV standard and the city mayor’s ambitious plan includes banning diesel powered cars by the same date.

Paris scores badly in SFC’s ranking on local emissions, partly because the data available predates the city’s new air quality plan. Like many cities, Paris has a problem of PM10 and NO2 emissions and while it reduced NO2 levels from 96.5µgm³ to 81µg/m³ between 2009 and 2013, that figure is still more than double the EU threshold value.

However the introduction of LEZs, for all vehicles or just for HGVs, remains an effective measure for cities looking to reduce local emissions, says Bund’s transport policy research assistant Arne Fellerman.

“In several cities in Germany where LEZs have been implemented and their effects studied, such as Berlin, Leipzig and Munich, all have detected substantial reductions in soot, or black carbon,” Fellerman says.

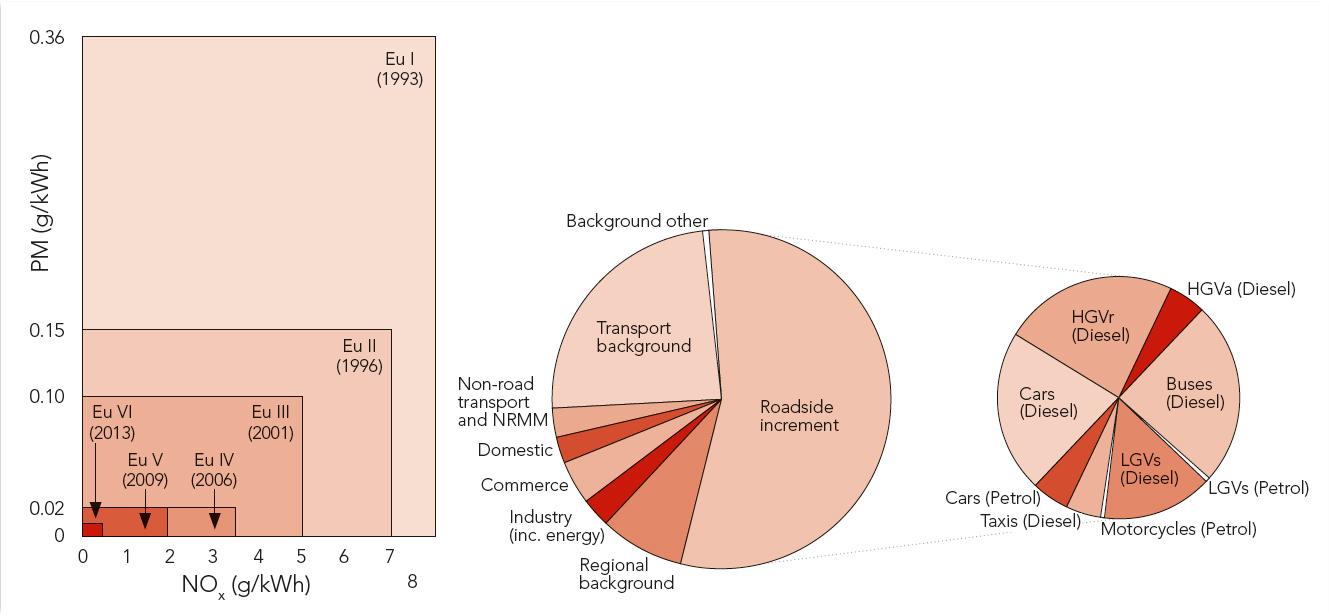

“It is difficult to detect a change in the EU emissions criterion of PM10 as a result of LEZs, because levels of PM10 are only marginally influenced by quantities of soot. We always advise that LEZs are introduced with the requirement for vehicles to be fitted with particle filters and with black carbon measured. Studies so far have included all vehicles, whereas it’s the larger diesel engines that produce the greater number of particles.”

A complex picture

The SFC campaign helps to illustrate the very complex make-up of emissions and air quality measurements. While there are many different emissions particles and gasses to be considered, targeting a value for PM2.5 is important due to its correlation with LEZs, Fellerman says.“Comparisons between emissions from cars and HGVs and areas of low concentrations to show the effects from different vehicles are very difficult, as there are so many other factors at play, such as background levels and ammonia from agriculture,” he says.

“We advocate LEZs as an effective measure for encouraging better air quality through the modernisation of fleets.

Introduction of LEZs makes sense for driving down emissions, but it’s no panacea. It’s just one measure in a much wider picture of air quality and emissions reduction.”

Other aims

Restrictions on HGV access are underpinned by other aims. Both Rome and Paris have introduced partial, time related HGV bans, partly to reduce traffic congestion.

Vehicles over 7.5 tonnes cannot enter Paris during the morning peak period (6am to 10am) on Mondays or on the day after a public holiday. Nor can they exit the city during Friday evenings or the peak evening period before public holidays.

This is understood to have produced a limited reduction of traffic congestion. An

These results appear to make a good case for extending Paris’ HGV restrictions to every day of the week.

A similar peak-time HGV ban has been called for in London – Europe’s second most congested city - for safety reasons after a number of fatal collisions with cyclists.

A steep rise in the numbers commuting by bike in London has brought an apparent safety problem to the fore – although accident statistics show that overall cycling safety is actually improving per head (of cyclists). However, a high proportion of fatalities that have occurred come from collisions with trucks and last year seven out of eight cyclist deaths in central London involved HGVs.

Political distraction

Andrew Gilligan, cycling strategy advisor to the Mayor of London, carried out a feasibility review of a peak time HGV ban in central London. The proposal was rejected; at the time Gilligan said the idea was a “distraction” from the main issue of improving the safety of interaction between HGVs and cyclists. While acknowledging that trucks are involved in a large number of cyclist fatalities, only three of 42 deaths between 2012 and 2014 occurred during the morning or evening rush hours.

However, trucks don’t enter a city without reason – they are either delivering or collecting goods and according to the UK’s Freight Transport Association (FTA), excluding HGVs from central London would be unworkable and counterproductive in economic and safety terms.

Christopher Snelling, head of national and regional policy at the FTA, says: “We would expect a range of different responses to a peak-time HGV ban from freight operators. Some would change the times they enter the city, while others would reduce the size of vehicles used in the area where HGVs are excluded.

“This would merely serve to increase the number of vehicles in the city, which would be a lot less efficient economically; it would worsen congestion and safety. Smaller delivery vans have a higher fatality rate per tonne per kilometre travelled.”

Snelling acknowledges that to his knowledge, no-one has yet carried out detailed analysis of the likely effects of a total ban on HGV access. However, a greater number of smaller vehicles doing the equivalent work of HGVs would increase emissions per tonne carried, he says.

Substantial benefits

This claim seems logical, particularly so given that the EU’s Euro 6 emissions standard that applied to light diesel powered vehicles is generally recognised as a failure. In contrast, the Euro VI standard for heavy vehicles, including buses, is working, says Venn Chesterton, energy and environment divisional manager for consultant Transport & Travel Research.“Studies have shown that real life emissions from Euro VI engines are as good as the lab tests,” he says. This serves to back up an argument that LEZs that deter or prevent older, more polluting HGVs and buses entering the city centre can produce substantial benefits.

“Local authorities with limited knowledge of air quality management have asked us for a view on LEZs for all vehicles. We advise that it is actually better to target a known or controlled fleet, such as HGVs and public transport vehicles,” Chesterton says.

“For putting business cases together, it is certainly possible to add other benefits of HGV access restrictions; freeing up [road] space for public transport for example. But these are hard to quantify. There is a need for more research on all sustainability aspects of LEZs. Stockholm and Copenhagen, for example, score highly on liveability, but it all comes down to willingness to pay. No such measure is free; all fleet upgrades eventually come at a price for consumers.”

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR: Jon Masters is a freelance journalist with considerable experience in the transport sector and a Contributing Editor to ITS International.